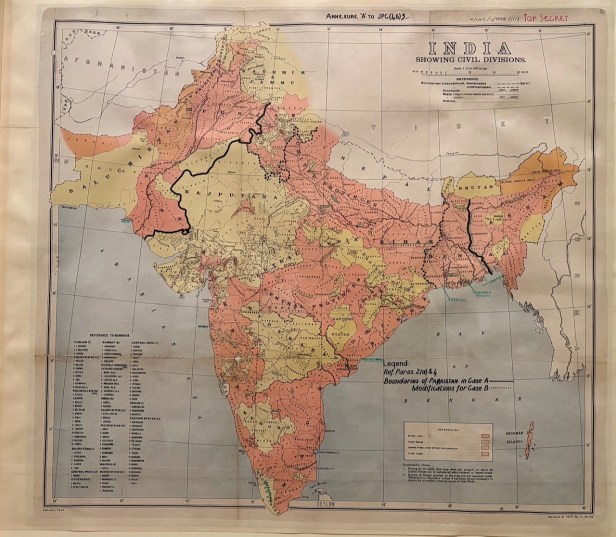

This map – marked “Top Secret” – was to result in one of the worst atrocities in history: the slaughter that occurred when India was partitioned in 1947.

The map was drawn up on the orders of the British Viceroy, and this secret map is part of an exhibition in the British Library.

The Partition of India

India had been under direct British rule since 1858, although the British East India Company had held parts of the sub-continent for far longer. By the end of the Second World War the British government realised it could no longer rule India. The main Indian parties, Congress and the Muslim League would no longer tolerate it.

The Labour government was committed to a rapid transfer of power but “hoped to leave behind some form of united India.” Intense negotiations took place between the key Indian leaders: Jawaharlal Nehru, for Congress which represented most Hindus and some Muslims and Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who represented the millions of Muslim voters who called for their own state.

By early 1947, British ministers had concluded that partition was “the only answer” to avert civil war, and Mountbatten announced in June 1947 that the country would be divided into Hindu‑majority India and Muslim‑majority Pakistan as part of the independence plan.

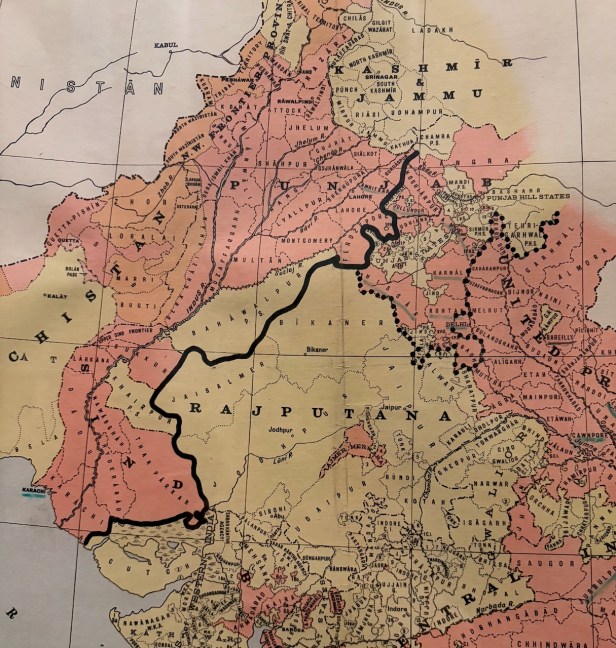

The British government formally agreed with Mountbatten’s plan in June 1947 to transfer power on 15 August 1947 and partition Punjab and Bengal, embedding partition within Britain’s chosen mechanism for decolonisation. The map created East and West Pakistan, which was separated by about 1,000 miles (1,600 km).

The resulting bloodbath

The map was drawn up by a British civil servant who had never visited India before and who was advised by senior Hindu and Muslim officials. He was Cyril Radcliffe. The British believed that his “ignorance of India would equal impartiality.” He left India before the decision was made public and never returned.

The map divided the Punjab, leaving its Sikh community cut in half, with some in India and some in Pakistan. It is said that Nehru was deeply distressed and emotionally affected when confronted with the extent of Punjab and Bengal’s division and the human cost implied by the award. He is said to have burst into tears.

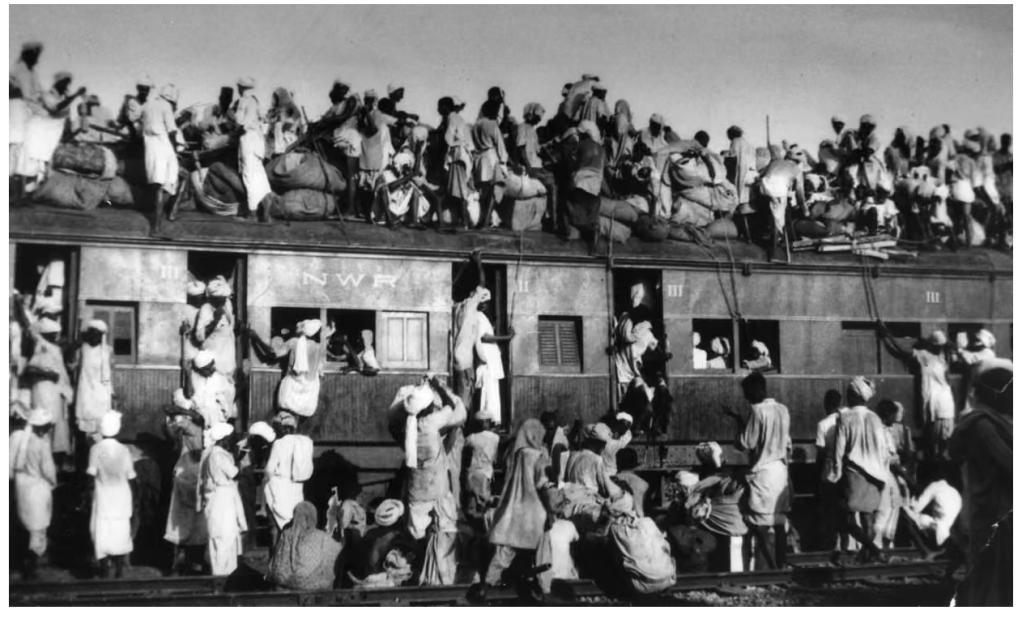

When Partition arrived massacres erupted primarily in Punjab and Bengal as Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims turned on each other, with estimates of deaths ranging from 200,000 to over 1 million (some sources suggest up to 2 million). Some 12–18 million people were displaced in the world’s largest mass migration. This was the recollection of Moni Mohsin.

Armed mobs, often supported by local militias or demobilized soldiers, conducted systematic ethnic cleansing: villages were torched, trains carrying refugees were derailed and attacked (earning them the grim name “blood trains”), women faced mass rape, abduction, forced conversion, or murder to “preserve honour,” and children were killed or orphaned en masse.

Trains filled with refugees crossing the border were stopped and every man, woman and child on board slaughtered. Only the engine driver was spared, so he could take his grisly cargo to its destination. Women – some as young as 10 – were captured and raped, and pregnant women’s bellies were slit open. Babies were swung against walls and their heads smashed in.

Key hotspots included the Rawalpindi massacres (March 1947, targeting Hindus/Sikhs with 2,000–7,000 deaths), post-15 August riots in Lahore/Amritsar, and revenge killings in East Punjab, fueled by rumors, political incitement from Congress, Muslim League, and Akali Dal leaders, and the collapse of policing amid British withdrawal.

The Punjab Boundary Force (55,000 troops) proved inadequate against the frenzy. Violence peaked during October 1947. The trauma lingers in South Asian politics, with unresolved border disputes and generational scars from the atrocities.

India was left divided. There was a further division when Pakistan itself split. East Pakistan seceded from West Pakistan in 1971 to form the independent nation of Bangladesh after a brutal nine-month civil war marked by genocide, mass displacement, and Indian military intervention.

Bangladesh emerged as a sovereign state recognised rapidly by India and others, while Pakistan lost half its population and faced military humiliation. It reshaped South Asian geopolitics with enduring India-Pakistan enmity.