Hapoel Tel Aviv – one of Israel’s top teams – let the 12-year-old Milyardo Asrat on its boys’ team as a favor to the asylum-seeker community. Now at 18 he dreams of representing the national squad – and not living on a construction site.

Source: Ha’aretz

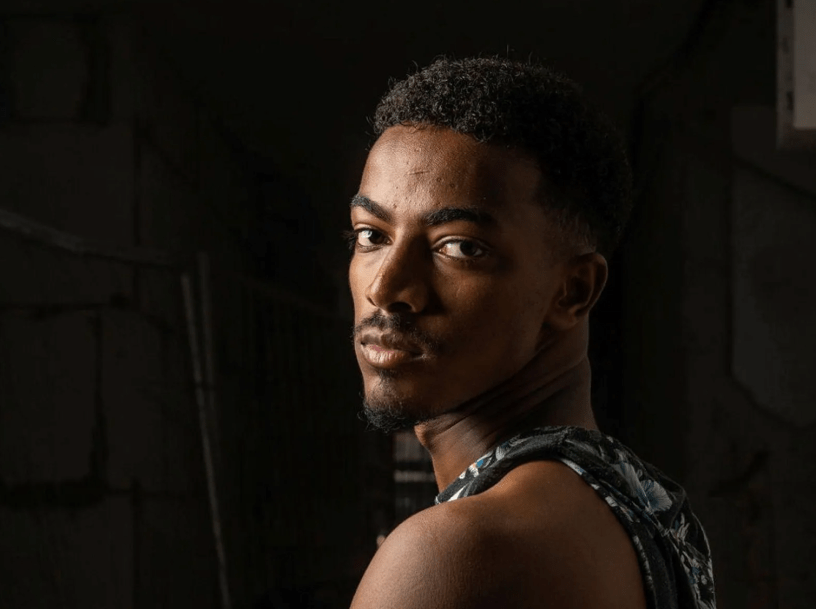

Asrat Tekie and his son, Milyardo Asrat. “You don’t know what it’s like to apply for a visa and be scorned and humiliated,” the father says.Credit: Hadas ParushItay Goder

Sep 14, 2023

“I won’t let him,” says his father, Asrat Tekie. “Only for practice and then straight home. Absolutely not to roam around outside. It’s very dangerous to be on the street now. There’s no way I’ll let him.”

It was four days since the riots in south Tel Aviv between supporters and opponents of the regime in Eritrea. The atmosphere was still tense. Eritreans feared that the police might crack down.

“That kind of stuff doesn’t interest me,” Tekie says. “I was at work when the protests started – I was at the restaurant in Jaffa as usual, and suddenly I heard about what was happening there. I was in shock.”

“Yes, very much so. The images I saw from there – I’d never seen anything like it. Even if you’re hurting, if things are hard for you, that’s not the way to behave. This isn’t our culture. There are protests like this by Eritreans almost everywhere in the world where our community lives. But nowhere else do they attack police officers. This isn’t the way to ask for what you deserve.

“On the other hand … the rage against the police is based on a genuine feeling. When for so long you’re made to feel that you’re nothing, that you’re worth nothing, when you’re disparaged every minute and every second, then eventually it explodes. I’m not saying that I’m justifying what happened there. But I’m Eritrean and I know what my community goes through every day here.”

What does it go through?

“This country is abusing us. They don’t bother to look through the applications by refugees, they scorn us, and it blows up. What happened now, I think, is just the beginning. And I’m not talking about what’s happening in Eritrea. I’m talking about the reality of our life here, in Israel. You don’t know what it’s like to apply for a visa and be scorned and humiliated. I don’t want to die, I want to live.

They don’t bother to look through the applications by refugees, they scorn us. How long will this situation go on?Asrat Tekie

“I’m not an opponent or supporter of anything; all these riots don’t really interest me. I’m focusing on my son and on my life. How long will this situation go on? I just heard Netanyahu say, ‘I’ll deport them.’ I don’t think he will. There’s a law, isn’t there?

“Israel says that it’s a Jewish and democratic state, but I want to see that. From what I see, it’s neither Jewish nor democratic. It’s not Jewish, because Jews aren’t the only ones who live here. There are Muslims and Christians here, and people who have no religion.

“But it’s also not democratic. Where’s the democracy? I was born in a refugee camp. My son was born in a refugee camp. I brought all the right documents from the UN. Why don’t you recognize me as a refugee? Why doesn’t the state approve us as refugees? They ask me, ‘So why did you come here?’”

- Israel’s shameful, xenophobic detention of Eritrean asylum seekers

- Israel must free the 50 Eritreans it is holding without trial

- Unwanted and unrecognized by Israel, thousands of Eritrean refugees have left for Canada

How do you respond?

“I came from Sudan, but that’s not my country. My parents fled Eritrea in 1980 when the problems started with Ethiopia [as Eritrea sought its independence]. I was born in 1983. I lived my whole life in a refugee camp in Sudan. Have you heard of Wad Sharifey? It’s the largest refugee camp in Sudan; it has 30,000 to 40,000 people.

“Man, it’s awful there, I’m telling you. When the wars in Sudan started, between the Sudanese, I fled because there was nothing for me there, it’s not my country. What am I going to do there in a state of war? Then I came here. Look, I don’t want to go on talking about it, Milyardo is listening. My son is a sensitive kid. I don’t want to hurt him.”

When he was 18, Tekie met the woman who would become Milyardo’s mother. “She was Eritrean, too, a Christian like me, even though we attended an Arab school. We got together pretty quickly, and even though we didn’t get married, she got pregnant. Not long after Milyardo was born, we broke up for good.

“I wasn’t going to leave my son, there was no question in my mind. His mother was a pretty girl, and I knew she’d very quickly find herself a new man. I wasn’t willing to have another man raise my son. I couldn’t accept that. We went to court and I was awarded custody of Milyardo. I’ll never forget it. When he was exactly 6 months old, he was placed in my custody.”

How were you able to raise him?

“The whole family lived together. My mother raised him until he was 2. He became very attached to my sister, and to this day she’s like a mother to him. When he was 2 and the war in Sudan started, I knew we couldn’t stay there. We were a group of two men and three women, and we decided that we couldn’t stay in the refugee camp any longer. There were two possibilities – flee to Libya and go from there to Italy, or come to Israel.

“I was terrified to get on a boat. At the time there were lots of people who left Sudan and got on a boat and didn’t make it. I said to myself: ‘If I’m going to die, then let it be in the desert. I don’t want the sea to take me. I talked to some smugglers. They demanded $1,400 per person to take us to the Egyptian border. That was a lot of money. I paid $2,800 for me and my sister, and I carried Milyardo with me.”

It sounds crazy.

“It was. The trip took a week. When we reached the Israeli border, the soldiers there were shocked that he was still alive. They immediately gave him food and drink; they were really okay. And my Milyardo is such a good boy. He never complained, he hardly cried. He’s been through so much in life.”

Tekie served a stint at a detention facility. “Wow, it was awful,” he says. “The biggest problem was that they didn’t bring an interpreter. They didn’t understand us and we didn’t understand them. It was a nightmare.” Either way, he then received a temporary visa and a one-way bus ticket.

“I remember arriving at the Tel Aviv Central Bus Station. I was holding Milyardo. I didn’t know what to do, where to go. I’d been told that I needed to get to Mesila, a place that helps people like us,” Tekie says.

“Today I know that it’s across the street from the bus station, but that day when we arrived I stopped a taxi driver who took us on a long ride, then let me off there and asked for 50 shekels [$13]. I paid him, got out of the cab, looked around, and thought – ‘Wait, haven’t I been here before?’ It turns out all I had to do was cross the street. That was my first experience in Tel Aviv. I still laugh about it with Milyardo.”

Without soccer, I don’t know where I’d be today. I might even have been a criminal.Milyardo Asrat

In those first days, the two slept on a bench in Levinsky Park in south Tel Aviv’s Shapira neighborhood, where many African asylum seekers live. Then it was a few more apartments in scrappy south Tel Aviv neighborhoods. “And that was it. We started our new life.”

Milyardo Asrat’s name is actually Milyardo Tarka, after his grandfather. “But here they wrote Milyardo Asrat,” his father says. “With us, the surname is the grandfather’s name.”

Milyardo looks on as his father speaks. The location couldn’t be more apt: 22 Etzel St. in south Tel Aviv’s Tel Giborim neighborhood is currently a construction site. Some of the buildings are undergoing massive renovations. Most of the tenants have left.

Milyardo and his father have remained in their first-floor apartment in the middle of the construction site. Because of the safety risk, every time they come in and out they have to coordinate with the foreman. The noise is deafening. The area is shrouded in clouds of dust, so the father and son have to keep their windows shut. They don’t have air-conditioning.

“I really hope the day will come when I’ll be able to get us out of here,” says Milyardo, who plays behind the main striker for Hapoel Tel Aviv’s under-20 team (“and sometimes on the right wing too”).

“This is my second year on the youth team, and I’m already getting money from Hapoel,” he says. “I think that if I stay good, at some point I’ll get my chance with the main team. We have a new coach now, Ohad Kadousi. He believes in me, and I really hope to reward his faith in me on the field.”

Milyardo only started playing organized soccer when he was 12. As a contribution to the Eritrean community, Hapoel Tel Aviv let him practice with the club’s boys’ team a few times a week, only to discover that they had a soccer star on their hands.

They didn’t believe that I, as a man, could raise my son alone.Asrat Tekie

The process wasn’t simple because Milyardo is a temporary resident in Israel. It took six months for him to get an official player’s card, but after that, Milyardo began playing league games. “He’s a tremendous player with remarkable talent,” says one of the club’s under-20 coaches.

“His technical ability is amazing. His dribbling is terrific and his kicking from outside the penalty area is at a very high level. I don’t remember having any problems with him. He’s very warm and easygoing, and he cheers for his teammates.

“And it felt like you never knew what he was going through. The world he lives in was closed to us; we didn’t really know about it. Sometimes you could see this on the field. He had ups and downs that weren’t due to physical reasons. I assume that the situation at home was very hard on him. But he didn’t talk about it. He hid it amazingly well.”

Ofir Haim, the coach of the national under-20 team, says that if it were possible, he’d gladly consider calling on Milyardo. “He’s a very talented player with excellent abilities,” Haim says. “There’s no telling how far he’ll go, but it’s absolutely clear that he’s a special talent. But talent alone is never enough. We’ll have to see how he progresses and improves his abilities in the league.”

Milyardo says he knows that he needs “to maintain more stability and supply the numbers,” and people at Hapoel Tel Aviv say it’s just a matter of time before he makes the big club. Hapoel officials are trying to secure Milyardo’s refugee status so he can receive protections as part of the UN Refugee Convention of 1951.

They’re also encouraged because Milyardo is opening up about his life and background. He recently took part in the new film “Running on the Sand,” which will premiere next month. It’s the fictional story of an Eritrean refugee who assumes a false identity as a soccer player and turns out to be good at soccer. Milyardo plays the main character’s brother.

How important is soccer to you?

“Are you kidding? Aside from my father, my aunt and my dog, it’s the most important thing in the world to me. Without soccer, I don’t know where I’d be today. I might even have been a criminal, even though I finished high school here. I can’t go to university yet. I can’t get a driver’s license. I don’t really have anything besides soccer.”

Milyardo isn’t exaggerating. His father says that since he was 4 he has slept clutching a soccer ball. “I would take him to Levinsky Park all the time so he could play soccer,” Tekie says. “I would sit there for four hours and never take my eyes off him for a second – not because I know anything about soccer. I was just terrified that they’d try to kidnap him.”

Kidnap him?

“You don’t know what I mean? [The Israeli authorities] put me through terrible trouble with him. They didn’t believe that I, as a man, could raise my son alone. At first, they told me: ‘You’re a father. You’re not a woman. You can’t raise a child.’ They took me to court. I told them there: If you’re going to take my kid away, I’d rather be deported to Sudan. I’d rather die there than have you take my child from me.

“Also, what did I do wrong for them to take him from me? To this day, I work 14 or 15 hours a day. They’d come to my home and check how he was sleeping, what he was eating, where he was playing. They wanted to take him away to a boarding school, but I wouldn’t agree.

“One day, when he was in elementary school in the Hatikva neighborhood, they took him from school without telling me. To Beit Shemesh!” – a town near Jerusalem. “They wanted to give him to a couple with no children. I made a scene at the school. I said to the principal: ‘How could you let him go without my permission?’ She asked me to forgive her. Look, if he had wanted to go, he would have gone. But he always said: ‘I’m staying with my father.’”

Milyardo adds: “I would be very happy to stay in Israel and represent the country, because I love this place. But I don’t have a passport, so it’s not possible. All my friends are from here.”

And his father concludes: “I have no idea what will happen. I think that in any proper country, he would have been granted status long ago. But forget soccer – this boy grew up here. He speaks the language. He was born in a refugee camp. His father was born in a refugee camp. He deserves to have refugee status.”