No-one doubts the severity of the food situation in Tigray. Even if it is too early to call it a famine, it seems clear that it is heading in that direction.

This is what the latest report from the Famine Early Warning System says:

“In early 2024, with the likely early start to the lean season in northern Ethiopia, household food stocks are depleted and poor households are expected to rely on income-generating activities to afford food; however, income from sources like firewood/charcoal sales, labor, petty trading, and livestock are expected to remain low. This will drive a resurgence of wider spread Emergency (IPC Phase 4) outcomes in many areas of Tigray and northeastern Amhara.”

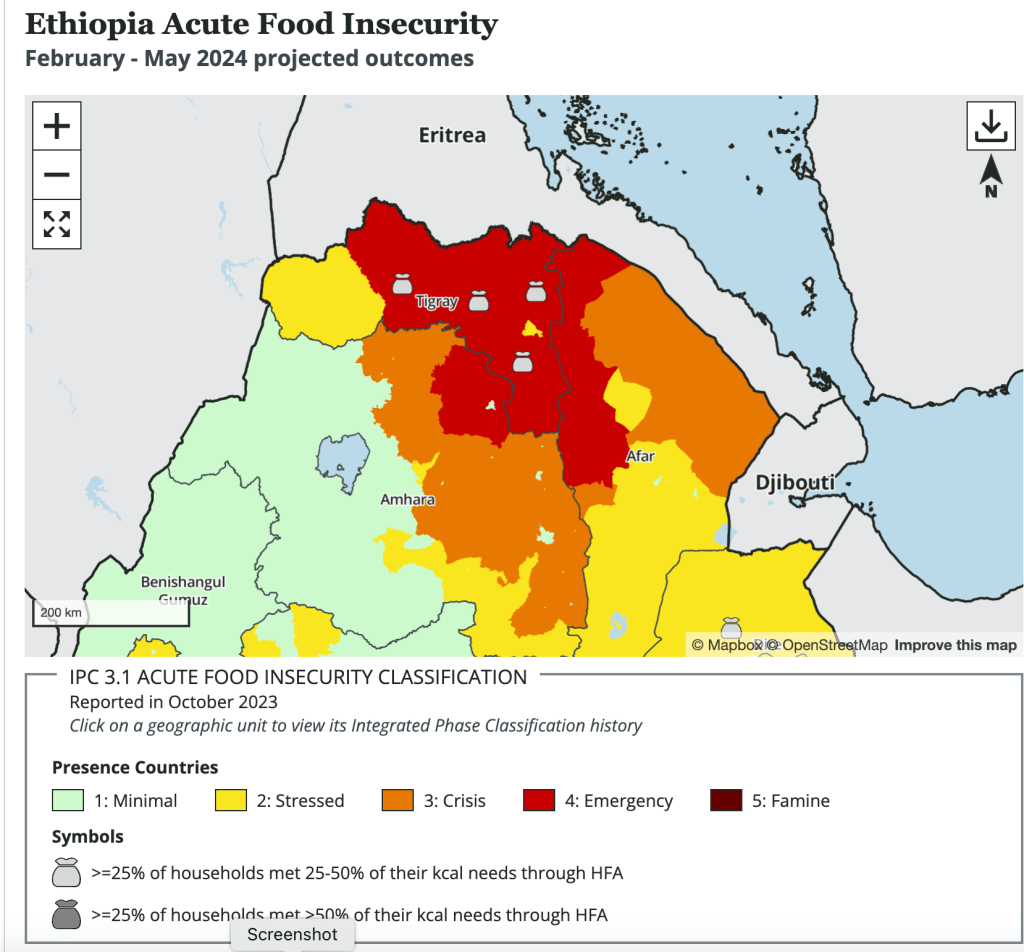

Here you can see the same information in a visual form, looking ahead.

Why is this happening, if we all know it is coming?

There are three reasons for the critical food situation.

- Problems with climate and a lack of fertilizer, plus the results of the tragic war of 2020 – 2022 which killed so many able-bodied people and devastated the agriculture.

- The halting of food aid by the World Food Programme and USAID.

- The diversion of food supplies by members of the Tigrayan elite – by the TPLF and the military. This was replicated at a national level, with the federal authorities also involved. How high did this go, and were some of the international actors also involved?

Since the first is well known, I will instead concentrate on the second and third.

World Food Programme and USAID halt aid

Both of these key sources of food aid, upon whom the Tigrayan people have relied for decades, halted their supplies earlier this year.

On 3rd of May USAID’s Samantha Power put out a statement saying that: “We have made the difficult decision to pause all USAID-supported food assistance in the Tigray region until further notice.”

“The United States is the largest humanitarian donor to Ethiopia, and we remain committed to the Ethiopian people. Recently, however, USAID uncovered that food aid, intended for the people of Tigray suffering under famine-like conditions, was being diverted and sold on the local market. Immediately after this discovery, USAID referred the matter to USAID’s Office of the Inspector General, which began an investigation. We also launched a thorough review of our programs, and as part of the investigation, deployed senior leadership from our Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance to Ethiopia to conduct further assessments.

Following this review, USAID determined, in coordination with the U.S. Embassy in Addis Ababa and our implementing partners, that a temporary pause in food aid was the best course of action.

The U.S. government has raised its concerns with officials from both the Ethiopian federal government and the Tigray Interim Regional Administration. Both federal and regional authorities in Ethiopia have expressed their willingness to work with us to identify those responsible and to hold them accountable. USAID stands ready to restart paused food assistance only when strong oversight measures are in place and we are confident that assistance will reach the intended vulnerable populations.”

The World Food Programme made similar statements in what was clearly a co-ordinated decision.

Why did WFP and USAID act in April?

Perhaps the key sentence came at the end of Samantha Power’s statement: “As a responsible humanitarian donor accountable to U.S. taxpayers, USAID institutes robust oversight, monitoring, and evaluation systems so that U.S. assistance is used only by those for whom it is intended.”

To put this in plain language: both agencies had known about the diversion of aid for years. The story was probably about to finally break and they decided to act. If the news had broken before they halted the aid, their jobs could have been in jeopardy.

USAID was so concerned that it referred the issue to the government watchdog – The Office of Inspector General (OIG). This is what the OIG said in a carefully worded statement.

“After USAID alerted OIG about the alleged diversion of food in Ethiopia, OIG identified multiple potential fraud schemes including corruption in the beneficiary selection process and exploitation by vendors purchasing food from beneficiaries. OIG also responded to allegations that beneficiaries were compelled to give a portion of their assistance to local officials and armed groups.”

What is the evidence for this?

As Deutsche Welle reported in June: “An internal briefing by a group of foreign donors said that the US Agency for International Development (USAID) believes that food aid had been stolen for use by Ethiopian military units. USAID has described the theft as “widespread and coordinated.”

As the Guardian report in June put it: “The UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) and the US Agency for International Development (USAid) are still piecing together how much food was taken. While the true scale may never be known, aid workers briefed on the initial findings of the USAid investigation say the agency believes this could be the biggest ever theft of humanitarian food and that Ethiopian government officials are deeply involved.”

But none of this was new.

The Guardian spoke to aid officials off the record. “This is a system everyone supported for decades, donors and partners alike,” says one. “The scale is only new because they didn’t do anything about it. They left it to fester.”

A spokesperson for WFP refused to specify who was responsible for the theft, but says the amount of food stolen was “significant”. Much of the theft had occurred “post-distribution – meaning after the assistance has been handed to the beneficiary”. These supplies then found their way on to markets.

“It is WFP’s job to strengthen our mechanisms to make sure it doesn’t happen again,” the spokesperson says.

Where did the diverted food aid go?

The best evidence for this was supplied by the Washington Post.

“Flour made from donated wheat was being exported to Kenya and Somalia even as Ethiopians starved, the diplomat said, adding that WFP was “negligent or complicit.”

In the Somali region, which has been grappling with the worst drought in generations, mill managers told the investigation team that they routinely bought bags of wheat in bulk that were branded with USAID and WFP logos, the diplomat said. The bags were unopened, indicating it was not middlemen buying from families who had sold part of their rations, said the diplomat. The border town of Dolo Ado in Ethiopia has two functioning flour mills even though the nearest wheat production is more than 300 miles away, he noted.

A witness who visited one of the mills in Dolo Ado this week sent The Post photos of 50-kilo bags labelled USAID and WFP stacked outside it.

The USAID investigation team witnessed the direct involvement of the Ethiopian National Defense Force in the diversion in the city of Harar, the diplomat said.”

The New Humanitarian went further:

“USAID points to corruption in the aid delivery system as the underlying culprit. Its probe identified “a country-wide diversion scheme” coordinated by senior officials in both federal and regional governments, with food meant for hungry people sold on commercial markets or supplied to military units.

Significant diversions of USAID-funded food were witnessed by investigators in seven of Ethiopia’s nine regions. In one example, enough stolen US-supplied wheat to feed 134,000 people for a month was found for sale in a single market in Tigray. Private grain and flour traders also played a role in the diversion scams, the agency noted.”

Tigray’s involvement and the role of the federal authorities

This was pointed to by the New Humanitarian, which said that “the Tigray regional government has launched its own inquiry, and this month it acknowledged that misappropriation had taken place at both the federal and regional level. It also accused Eritrea of being involved in the plunder of relief supplies.”

It is not clear from the evidence whether some bags of aid, once opened, were given to members of the armed forces. Or was aid taken directly from warehouses and sold? It appears that both took place.

The Tigrayan administration has not so far detained or prosecuted the key individuals who participated in this diversion of aid. Were they senior members of the TPLF? Or were they members of the armed forces? One is left wondering whether they are so senior that they are effectively “untouchable”. That is the suspicion that some in the Tigrayan diaspora are now harbouring.

But the corruption clearly did not end in Tigray.

The Ethiopian federal authorities were involved, although quite how high up the ladder this went, we do not know. Tigray is named, but the corruption took place in other parts of Ethiopia.

We also don’t know what steps are being taken to prosecute federal officials, or the international aid agency staff who oversaw this multi-million dollar aid programme.

What are USAID and the World Food Programme doing now?

Both have conducted in-depth reviews about what took place, but they are so sensitive that neither report has been made public. The corruption probably goes too high up in Ethiopia and may well involve members of the aid community as well. Until the reports are released we can only speculate.

Both agencies say they have resumed aid. But it appears to be too little and – for many who have starved to death – too late.

In November the WFP put out a statement saying that it would start resuming aid, but with a new system in place.

“This is the culmination of a complete evaluation and reset of WFP operations in Ethiopia focused on transparency, evidence, and operational independence. WFP’s new approach is underpinned by a robust set of safeguards and controls that have been extensively tested.

These include:

- Using clear criteria to identify and digitally register the most vulnerable households and people;

- Working with local communities to verify those in greatest need;

- Reinforced commodity tracking to follow food movements from warehouses to beneficiaries; and

- Increased monitoring and community feedback and reporting mechanisms that will unearth and quickly escalate potential misuse of food aid.

“WFP teams and our partners have been working around the clock to get to this point”, said Cindy McCain, WFP Executive Director. “This approach, supported by both the Government and partners, sets a new standard for humanitarian assistance in the country. We are now fully focused on getting food aid into the hands of Ethiopians who have gone too long without it.”

USAID took a similar position on 14 November.

“USAID is committing to a one-year trial period of the nationwide resumption, during which we will continuously monitor and evaluate the efficacy of the reforms put in place by USAID, implementing partners, and the Government of Ethiopia.

These widespread and significant reforms will fundamentally shift Ethiopia’s food aid system and help ensure aid reaches those experiencing acute food insecurity. Specifically, these measures strengthen program monitoring and oversight, reinforce commodity tracking, and improve beneficiary registration processes by USAID partners. The Government of Ethiopia has agreed to operational changes in their work with humanitarian partners that will strengthen our partners’ ability to identify and approve beneficiaries based on vulnerability criteria. The Government of Ethiopia has also committed to providing unimpeded access for USAID and our third-party monitors to review a wide range of sites throughout the country.”

When will the system be up and fully functioning? And when will the people of Tigray stop dying of hunger? To these critical questions there are no answers.