This is a background briefing ahead of the King’s College Webinar on 04 April 2024 From 12:30 to 14:00, London time. To attend please contact Professor Sue Onslow at sue.onslow@kcl.ac.uk

South Africa Elections – 29 May 2024

Martin Plaut & Sue Onslow[1]

Introduction

On 20 February 2024, President Cyril finally announced the date of South Africa’s 2024 general elections, to be held on 29 May 2024. This has long been described as a crucial election for South African democracy, and a great deal is riding on the outcome of the May vote, for South Africa itself, and the economies of the wider region.

The country’s main political parties have been in full campaign mode for months. These elections promise to be the most competitive since the National Party’s election victory in 1948, to be replaced by the African National Congress (ANC) on 27 April 1994, when Nelson Mandela was swept to power. In the past 76 years these two parties have dominated the South African political scene, only reaching out to smaller allies when it suited them. This has now changed. In 1994 the ANC received 62.6% of the vote in 1994, but since 2014 the party has been losing popular support. This trend appears to be accelerating. A wide range of opinion polls suggest that there is a high probability that the party will fail to win 50% of the popular vote. Since South African elections are held under a proportional representation system, this will leave the ANC needing to find allies to continue to govern.

It is not difficult to understand why this is happening. The ANC is today a party engulfed by venality. This was revealed in startling detail in the 6-volume report by the government’s own Zondo Commission into what was termed ‘State Capture’. Despite the public information, the ANC has decided to endorse candidates to stand in the election who were named by the Commission as implicated in corrupt practices.[2] The ANC is no longer the party of John Dube, Sol Plaatje, Oliver Tambo or Nelson Mandela. Its decline is personified by the case brought by Lonwabo Sambudla, who ran the investment arm of the ANC youth league.[3] Mr Sambudla, the former son-in-law of President Jacob Zuma, went to court to prevent the seizure of his Ferrari, Rolls-Royce, and Bentley – luxury vehicles he could not afford.

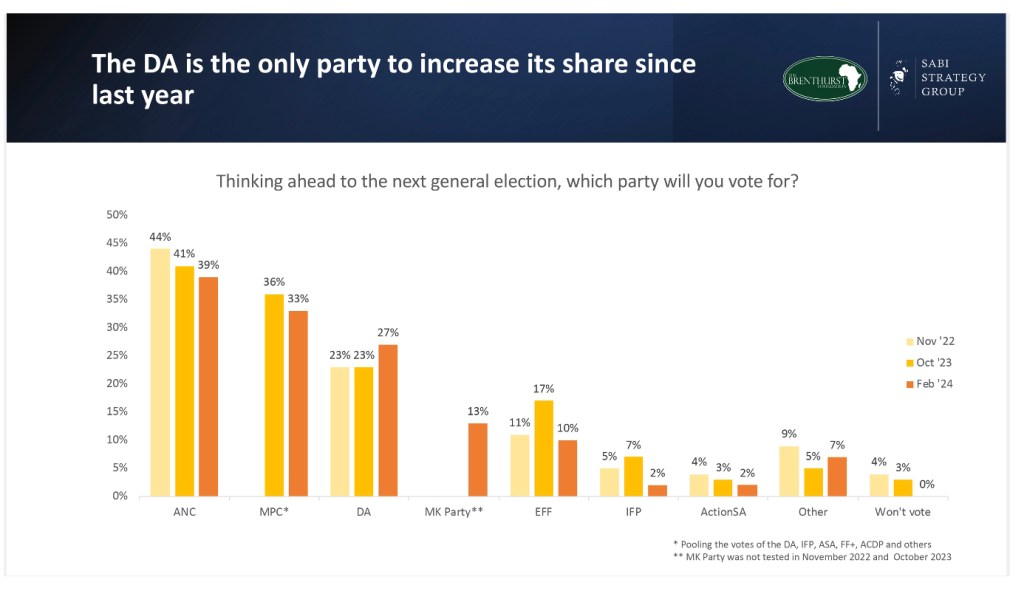

The likely candidates as potential allies are the ANC’s political rivals, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) or uMkhonto weSizwe (MK), Jacob Zuma’s new political movement. Recent polling suggests MK has overtaken the EFF in national polling (13% versus 10%), but there is still considerable time to go before the elections.[4] At the same time, the opposition, led by the Democratic Alliance (DA), has been mobilising its forces to mount a ‘Moonshot Pact’ alliance to wrest control from the ANC. They have plenty of potential partners to choose from: there will be more than 100 new political parties on the ballot, including ActionSA, the Patriotic Alliance, and Rise Mzanzi.

For the first time, independent candidates will also be on the ballot, following a ruling by the Constitutional Court that they could not be prevented from standing. It is clear that there is more to play for in these elections than there has been for many years.

Context

The 2019 elections were already characterized by pessimism and racial divisions.[5]

Five years on, South Africa’s political scene is even more uncertain. The country’s problems are well known:

- a stagnating economy with little or no growth (+0.6% in 2023);

- rising inequalities;

- adult unemployment at 32%, with youth unemployment standing at a shocking 50% of 18-30 year olds;

- endemic corruption which Ramaphosa has done very little to check since his inauguration as President in 2016;

- collapsing transport and electricity infrastructure, together with ‘water shedding’, with knock on effects on South African businesses;

- sharply declining profits in the extractive industries;[6]

- rampant crime statistics (for example, 27,000 murders per annum);

- a faltering education system;[7]

- emigration of professional talent.

Analysts have long predicted that South Africa is heading for a hung national assembly, and an era of coalition politics at national, as well as local level. This threatens national and provincial instability if the experience of chaotic metropolitan coalitions where such experiments have been tried is a bellwether.[8] The omens for stable governance and public service delivery are not promising. South Africa does not have a political culture of stable coalitions, nor one which admits to the concept of a loyal opposition. Every day new polls appear predicting a decline in support for the ruling ANC – the most recent forecast ANC support will dip below 40%.[9]

As the Brenthurst Foundationunderlines, with 33% of the vote, the Multi-Party Charter (MPC) coalition (DA, IFP, ActionSA, ACDP and FF+, among others) is just 6% behind the ANC.

This erosion of openly declared support for the ruling party can be put down to multiple factors: evident incompetence at addressing South Africa’s economic and social problems, endemic corruption, and voter disenchantment and apathy. That said, the ANC is likely to remain the largest party in Parliament, and thus the ‘deal driver’ in a future national coalition government. The questions remain how much voters will punish chaotic ANC/EFF coalitions and opt for alternatives; how widely party candidates and officials will be able to canvass for support; the threat of electoral violence and the size of the voter turnout. However, the threat of instability is real, and the example set by local government is poor. As Dumisani Hlophe a Deputy Director-General at the Department of Public Services and Administration argued: ‘The collapse of both the ANC-led, and the DA-led coalitions in the Nelson Mandela Bay, and City of Johannesburg Metros, respectively, is manifestation of political leadership instability of local government coalitions. This instability is also prevalent in the cities of Ekurhuleni and Tshwane, and the possibility of power changing hands to alternative, and equally fragile coalitions is high.’[10]

In the forthcoming election the tea leaves are harder to read at the provincial level: the disruptive effect of the proliferation of political parties has opened up the field. South Africa is now truly in the realm of plural politics, rather than post-World War II era of a dominant one-party rule. Before 2024 Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) was identified as the likely disrupter. Now, the decision by former President Jacob Zuma to set up uMkhonto weSize (MK) is the gamechanger in town. MK is predicted to take an appreciable number of votes from both the ANC and EFF in KwaZuluNatal – the second most populous province – where early indications from by-elections suggest the new party may poll up to 18-20%. (The wider impact of MK beyond Zuma’s ethnic community heartland is harder to judge.) The electoral attraction is Zuma himself, as MK currently has no declared policies, and the former President remains personally popular. MK is a vehicle for Jacob Zuma’s presidential ambitions, and a weapon for political point scoring against Ramaphosa and his ANC faction. It is clear that Zuma has no desire to be an MP as, if elected, he would lose a very lucrative Presidential pension.

The proliferation of other smaller, newer parties (300 at the last count) and independent candidates is another new phenomenon in South African politics. The motivation of these new actors ranges from honest determination to address the country’s multiple problems, single issue politics, to hopes for personal gain.[11] Some have a national profile, with leaders such as former Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba claiming that media pundits are calling the election wrong, and on-the-ground research shows far greater support for his party ActionSA. The Patriotic Alliance, led by Gayton McKenzie, is troubling commentators, given its overtly anti-immigration stance and reputed links to organized crime syndicates. It is possible that smaller parties will present significant demands as the price of their cooperation in any coalition. However, this explosion of political and individual candidates will not necessarily translate into impact at national or provincial level. A much larger effect is likely at municipal level, where politics is particularly fractious and divisive, because of the possible lucrative gains of access to state resources and self-enrichment. The rising number of assassinations of local politicians, officials and ward candidates in recent years is particularly troubling.[12]

Male 44.77%

The erosion of support for the ANC

Part of the problem is that the party has been in power too long, has run out of ideas and is losing cohesion. Zuma has continued to hold onto his ANC membership, despite forming a rival political party. (He is almost certain to be forced to out of the ANC,[13] but the gloves are now off.) The ANC’s secretary-general, Fikile Mbalula now openly admits that the ANC lied to parliament, pretending that a swimming pool built at public expense for Zuma was a ‘fire pool’ installed as a safety feature.[14] At the same time, Zuma continues to attract support from his home province, KwaZulu-Natal and has some following among younger South Africans who regard him as a radical. Recent by-election results suggests that MK will make substantial inroads into ANC rural support in KwaZuluNatal and Mpumalanga, with some commentators describing Zuma as a possible national ‘kingmaker’.[15]

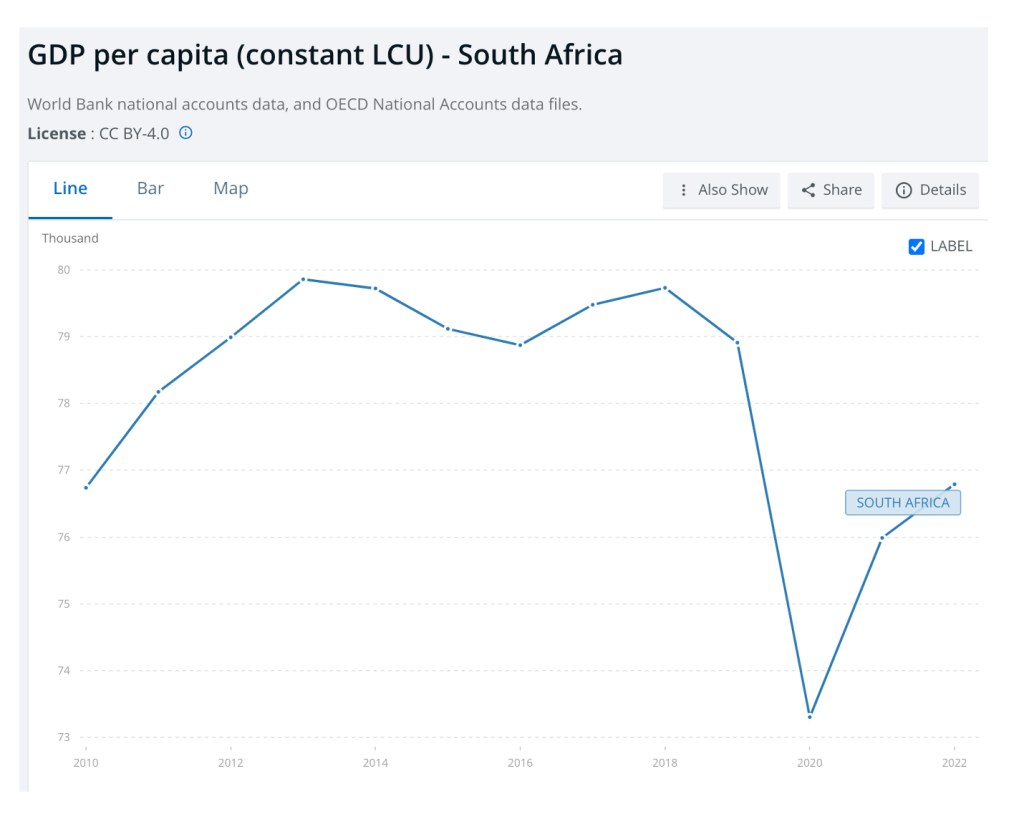

In the three decades that the ANC has governed the country’s infrastructure has been allowed to fall into decay while the economy has stagnated. Income per person has made some recovery after a sharp fall during the Covid pandemic but has failed to show any real increase (as measured by GDP per capital) since 2010.[16] As Andrew Kenny (BizNews 11 March 2024) succinctly describes:

the promise of dismantling apartheid’s racial inequality has given way to a deliberate shift towards economic disparity. The ANC, once a symbol of liberation, has fostered a black elite centred around political leaders, widening the wealth gap. The opulent lifestyles of the ruling class, coupled with policies like [Black Economic Empowerment] BEE, have fuelled class inequality, resulting in high crime rates.

Ordinary MPs now earn R1.2 million a year – about 4 times the annual earnings of the average worker in South Africa.[17] Furthermore, rather than reduce the inherited structural and racial inequalities of the apartheid era, Black Economic Empowerment has widened social, racial and class divides. Indeed, BEE has enriched a small black elite, at the expense of wider South African black, Indian and Coloured society. This black elite is centred around the ANC, but which also includes the South African Communist Party (SACP) and EFF leaders and has joined a cohort of rich whites who have continued to dominate business. The new black elite is entrenched in government positions at national and local level through cadre deployment. Not only does this ‘cadre’ class enjoy huge salaries and associated perks, in sharp contrast to working class and rural black South Africans. Recent revelations have shone light on the highly politicised control of appointments of SOEs and other government appointments by the ANC leadership, on the basis of political loyalty rather than professional capability. The strain on the South African exchequer has been compounded by ‘tender-preneurship’ – political well-connected black businessmen with preferential access to tenders and contracts at inflated prices, and insufficient oversight of service delivery.

However, it is the living conditions of ordinary South Africans that is a far more important issue.

Yet the black African population, upon which the ANC relies, still turns out and votes for the party, particularly in the rural areas. Under apartheid the countryside, termed ‘homelands’ were dumping grounds for the African peoples, which they could only legally leave with permits. (In 1994 the rural population comprised 46%.) Today no such restrictions apply and although there has been a migration to the cities, the rural areas are still home to a third of the population (32%).[18]

It is here that the people still vote for the ANC in huge numbers. It is not just that the party led the fight to liberate them from apartheid, it also led a government that brought electricity to remote areas of the country; spread homes across hillsides and – above all – provided them with social security benefits. Whole families, often unable to find work, come to rely on the small, but vital payments to family members who are disabled or retired. The maximum monthly state pension stands at R2 090 per month.[19] That is just US$122.00, yet it keeps whole families from destitution. Keeping it is vital, and this the ANC understands.

Competing appeals

The ANC running on its record and has been effectively campaigning for months. Cyril Ramaphosa, once regarded as the saviour of the ANC and South Africa, is facing a disillusioned electorate and presides over a fractious party. There are continued divisions on the National Executive Committee, which have hamstrung his time in office. Core vested interests within the ANC, and its allies in the SACP and COSATU, have stifled promised progress on corruption. Indeed, the wheels of South African justice seem to move at a snail’s pace, with a profusion of vexatious litigation which has stymied bringing individuals to book. Although ten individuals were barred from the ANC’s candidates list submitted to the IEC, the inclusion of over 90 others implicated in the Zondo Commission’s report findings on corruption and state capture, reinforce the image of a party which is determined to protect its own.[20]

As the response to Ramaphosa’s recent campaigning SONA address demonstrated, arguments about the ANC’s track record are wearing thin. The slice of a new black middle class is certainly better off than 30 years ago. The overwhelming percentage of South Africa’s voters are black (approximately 82%), and in rural areas. In the last election, despite the growing pessimism and lack of trust in government institutions, support for ANC held up more strongly in Black communities. However, Coloured and Indian communities, which comprise 8.2% and 2.7% of the population, feel themselves marginalized.

When elections come around the ANC of course plays to its strengths: its legitimacy as an opponent of white minority government, and its great leaders from the past, such as Nelson Mandela. Hardly surprisingly, ANC has been using all possible platforms to campaign – advertisements on the South African Social Security Agency platform in November 2023 prompted an outcry on social media.[21] But its primary appeal is simple: it warns the poor that they will lose their social security benefits if another party comes to power. It is untrue, but that hardly matters to ANC election campaigners. This negative campaigning is a tactic that the party has employed over several elections. A survey by the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Social Development in Africa (CSDA) carried out in the run-up to the 2014 election indicated that just under half of voters were not aware that the social grants that they received were theirs by right.[22]

The centre’s director, Leila Patel, said the finding was ‘worrying’ as it meant that these voters — 49% of the respondents — were not aware of their rights. The potential for political abuse is large, given that just under 16-million grant beneficiaries are receiving social grants amounting to R121bn this year. Agriculture MEC [Member of the Executive Council – provincial Minister] in KwaZulu-Natal, Meshack Radebe, for example, said in April that ‘those who receive grants and are voting for the opposition are stealing from government’. He said that those who voted for another party should ‘stay away from the grant’, as if social grants were gifts from the ruling party. In fact, these grants are funded by taxes in order for the government to meet its constitutional obligation to provide social protection.

There is ample evidence that ANC claims that voting for the DA will result in the withdrawal of these vital social welfare payments have an effect on rural voters.[23] Summarising the study, Professor Yoland Sadie described the role of social grants in deciding voter behaviour as important, possibly decisive.[24]

… social grants can provide an incentive for people to vote for the ANC, since a large proportion of grant-holders who support the party do not think that ‘they will continue receiving the grant when a new party comes to power’. A majority of respondents also agreed ‘that they would vote for a party that provides social grants’. Therefore, in a situation where one party has dominated the electoral scene for such a long time, and without having the experience of other parties being in power, it is difficult for voters to ‘know’ whether these benefits will continue under a different party in power – particularly if the official opposition has the legacy of being a ‘White’ party.

This is more complex than the counter charge of ANC electoral manipulation of illiterate or ignorant potential voters. Put bluntly, the stark reality is that very low-income rural South Africans feel they cannot take the chance. Child support grants for children under 18 comprise 71% of this meagre social award.[25]

Opposition Parties[26] and Tactics 2024

The electorate now has no shortage of parties from which to choose. Thanks to a ruling by the South African Constitutional Court, the 2023 Electoral Amendment Act permits individuals to run at national and provincial level for the first time. There are now more than 100 new political parties on the ballot, including ActionSA, the Patriotic Alliance, Rise Mzanzi, and Build One South Africa. With this dizzying array of single-issue parties, Conservative, Liberal, libertarian, white nationalist, faith based (although these categories may overlap with ethnicity and ideology), parties resulting from splits within the ANC (EFF, COPE, MK), or representing business (Change Starts Now),[27] at one level, the South African electorate is spoilt for choice.

The official opposition, the Democratic Alliance [DA] faces a two-fold challenge. The first concerns the party’s historical heritage and associated public perceptions: the DA has its roots in the white Progressive Party. For many years it fought apartheid with its sole Member of Parliament, Helen Suzman putting up doughty resistance to the racist legislation and practice. Bitterly attacked by the government for her stand, she won widespread respect and appreciation for her performance from 1961 – 1974. Since the end of apartheid, the DA has gone through several leaders, some of them black. Today John Steenhuisen is leader of the party and the official opposition. As a white politician he can (and is) be dismissed as representing an ethnic minority. The party certainly enjoys significantly higher favourability measures among white (80% favourable) and Coloured (69%) South Africans. (DA supporters are far less likely to have favourable views of South African public institutions.) The ANC goes further, suggesting to the electorate that the DA might see a return of apartheid.

Secondly, the multiplicity of parties raises the issue of competition for votes, and how best to address this: the DA has made no secret that it is organising a coalition of opposition parties to challenge the ANC. Recent polls suggesting that the overwhelming majority of respondents would like to see a national coalition running the country, rather than a dominant single party. Of the possible coalition permutations, the DA’s so-called ‘moon-shot’ is currently attracting approximately 33%. However, it is an untested experiment in national coalition building. ANC national chairperson Gwede Mantashe accused Steenhuisen of organising ‘apartheid parties’ to remove the ANC from power. ‘Steenhuisen is trying the impossible. He’s trying to organise all apartheid parties and parties of Bantustans to form a group that will defeat the ANC.’[28]

To resist these allegations the DA has now hit back. It is targeting the issue of benefits and grants, using social media:

It is a carefully targeted pitch. South Africans know that their electricity supply has collapsed, the police seldom answer calls for help and unemployment has hit families hard. Can the DA erode the ANC vote in key areas, including the rural communities? It is too early to tell.

The other radical contender is the Economic Freedom Fighters, under the former ANC Youth League leader, Julius Malema. Whereas the possibility of an ANC-EFF national coalition was strongly touted last year, with likely disastrous consequences for political stability and the South African investment climate, the party’s likely fortunes seem to be relatively eclipsed by the multiplicity of other parties, particularly MK. The EFF does not enjoy rural support, and the party is likely to be squeezed in KZN by Inkhata Freedom Party (IFP), the ANC and Zuma’s MK. However, the party is stronger in metropolitan areas where voters are very disenchanted by ANC incompetence. If indications from recent by-elections in rural KwaZuluNatal are repeated across the second most populous province, the EFF may poll between 10-12%. EFF disruptive performance in metropolitan coalitions has also alienated voters, in contrast to its perceived radical transformative agenda on land, national resources, and redistributive policies.

Media

Television, radio, print and social media is all vital for a free and fair election. The pressures and challenges facing South African media are significant. It is not simply the issue of concentration of media ownership, with the dominance of Media24 and its parent company, Nasper.

[N]ews outlets vie not only against traditional adversaries but also against an array of new entrants with bigger teams, more data and technology and crucially, zero cost of content production. This new information space is driven by engagement, which in turn is fuelled by content that stokes strong emotions and leads to a proliferation of extreme viewpoints and sensationalism.

In the chase for scale and cheap clicks, less “boots-on-the-ground” journalism was created, further eroding the foundation of quality journalism.

The advent of content aggregators has exacerbated the situation, with writers under pressure to churn out content at a breakneck pace, often at the expense of originality and depth. These trends have collectively undermined public trust in the media, depleted the reserves of public interest journalism, and contributed to the systemic failure of the journalism market.[29]

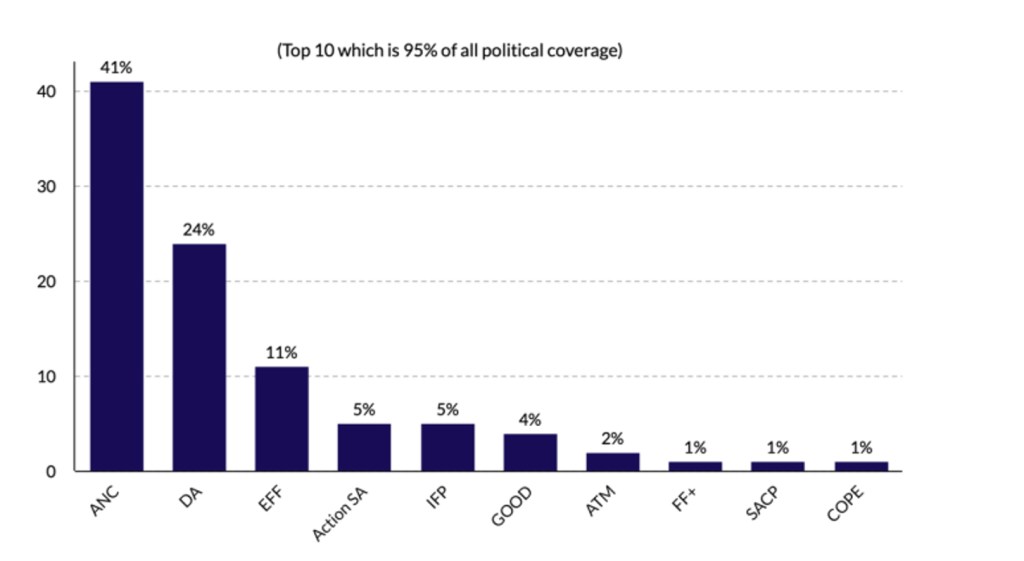

In the 2021 municipal elections, 95.4% of South African media coverage was judged to have managed fair and impartial.[30] The issue of equitable coverage was more complicated:

In 2021, there were 325 registered parties competing in the local elections. Inevitably and understandably, it was impossible to give equitable coverage to all of them. As the graph demonstrates, the top five parties accounted for 86% of the news coverage. With the current fracturing of the political system in the 2024 elections, this poses an even greater challenge to the media.[31]

Given the limited readership of legacy print media[32], social media will play a significant part in the election – in both positive and negative ways. In January 2024 South Africa had 26 million social media users, comprising 42.8% of the total population.[33] This is the principal platform of news and comment in the country for 46.5% of these users.[34] Social media messaging is more likely to reach younger voters, since 66% of 18-35 year-olds receive their news via social media platform. However, the credibility of the news is threatened by disinformation and misinformation and represents a significant risk for South Africa.[35] The dangers of bad actors driving disinformation has already identified around hot button issues such as immigration[36], continued access to social grants, and the veracity of the IEC. This underlines the importance of fact-checking sites such as Africa Check, and Real 411.org, set up by Media Monitoring Africa. [37] The difficulty, of course, is that given the speed of the spread of disinformation, and its enduring traction, fact checking sites are ‘behind the curve’.

There are other aspects of possible interference in the South African electoral process. The close relationship between the current ANC government and Russia has raised suspicions, voiced on social media, of substantial Russian funding for the ANC, together with possible Russian-funded disinformation campaigns against rival politicians and parties.

So what will decide this election?

Past elections provide fewer clues. South Africa is moving away from what might be termed post-apartheid ‘football team politics’ – i.e. ‘my party right or wrong’ – into an era which voters are holding parties and their leaders accountable, either through voting for alternatives, or by not voting at all. As RW Johnson has pointed out, this shift in voter preference and behaviour echoes processes of transition in other African countries following independence. However, this process is uneven. Under South Africa’s current system of proportional representation and the candidate list system, individual MPs remain unaccountable to their electorates.[38] Reform of the South African political list system, enshrined in the 1996 Constitution, will require an amendment supported by at least two thirds of the National Assembly (ie at least 267 MPs out of 400), and by the National Council of the provinces, with the supporting vote of six of the nine provinces.[39] Hardly surprisingly, the dominant ANC has shown little appetite for electoral reform, and consequently there has been no progress on this issue since the Van Zyl Slabbert electoral proposals of 2003.[40]

No matter the current disillusion with the ANC government, South African voters need credible alternatives. The 2019 election demonstrated that dissatisfied ANC voters only switched their votes if they believed that the alternative had a proved track record of competence, seemed inclusive, or if they had a favourable view of the party’s leader.[41] Promised policies such as clear and credible employment strategies, access to public health care are persuasive, as are negative campaigning and divisive issues, such as immigration.[42] The number of immigrants has doubled over the past decade), with repeated outbursts of xenophobic violence, and South Africa’s liberal asylum system is now a political issue.

Key Battlegrounds

As of 2023, 42.3 million South Africans were eligible to vote in the upcoming general elections. There has been a concerted drive by all the major South African political parties to boost voter registration. However, only 65.62% of those eligible have registered in the 23,000 voting districts – a total of 27,757,748, up from 26.7 million in 2019. In every age cohort, the percentage of women registered voters outnumber men. Voter turnout, particularly in the two most populous provinces of Gauteng and KZN, will be key to the final national result; as will the size of the rural vote.

44.77%12,425,792 (44.77%Female 15,331,956 (55.23%)

55.23

South Africa Registered Voters 2024 (%)[43]

Province

Gauteng 6,545,265 (23.58%)

KwaZulu-Natal 5,746,518 (20.70%)

Western Cape 1,770,757 (11.97%)

Eastern Cape 3,445,497 (12.41%)

Limpopo 2,783,838 (10.03%)

Mpumalanga 2,026,896 (7.30%)

North West 1,770,757 (6.38%)

Free State 1,459,502 (5.26%)

Northern Cape 658,056. (2.30%)

Gender and generational factors will also make a difference, with the current registered vote split between Male 12,425,792 [44.77%], and Female 15,331,956 [55.23%]. It is striking that the ‘born frees’ – those born since the ANC’s victory in 1994 – are noticeably disengaged from the democratic electoral process. Given the history of apartheid, refusal to register, followed by refusal to vote, are powerful political statements.

Registered voters by age group and gender[44]

18-19 Male (less than 1%) Female (approximately 1%)

20-29 Male (7.25%) Female (8.85%)

30-39 Male (11.39%) Female (13.19%)

40-49 Male (10.24%) Female 11.27%)

50-59 Male (7.37%) Female (8.99%)

60-69 Male 4.72%) Female (6.47%)

70-79 Male (2.0%) Female (3.38%)

80+ Male (less than 1%) Female (1.9%)

The issue will be whether these registered voters all turn out to vote. Declining voter engagement, particularly among young voters, has been a growing problem in South Africa. Of course, the country is far from alone in this: there has been a marked decline in young voters’ registration and engagement in democracies across the globe. In 2019 South Africa had a record number of eligible voters but saw a notable decline of 8% in overall voter turnout on the previous national polls. Indeed, in 2019, less than 50% of the voting age South Africans exercised their right to vote. This is a far cry from 1994, when 86% of registered South Africans cast their votes in the ballot box. A further steep decline in 2024 would raise questions of legitimacy of the final result.

Voter apathy and disenchantment is paralleled by accelerating distrust with state and public institutions. Age and gender are significant: men and younger voters (below 35) are less likely to vote. Afrobarometer has warned that while AI and technology may help to counter young voters’ disengagement, the most persuasive factor will be parties with a clear manifesto addressing youth unemployment. Alarmingly, ‘Youth are also more willing to tolerate a military takeover of the government if elected leaders abuse their power (56% among those aged 18-35 vs. 47% among those aged 56 and above)’[45] – a telling reflection of the sorry state of South African democracy. Voter calculations are also based on which political parties align with their interests. However, another crucial factor will be calculations over whether a political party have a credible chance of success.

The question is, will the decline in voter turn-out be greater than the slide in support for the ANC?[46] If so, the odds are the ANC will be returned as the largest party. If, on the other hand, the converse is true, coalition building will be more fraught, and the South African policy environment more unstable.

The degree to which voting is spread across opposition parties could be the decisive factor allowing the ANC ‘to govern nationally with a small junior coalition partner’. In the view of the Financial Times, ‘There will be no vice-president Julius Malema or his radical Economic Freedom Fighters calling the shots. In short, if investors are braced for a turbulent year, they may be in for an anti-climax.’

In addition to the size of electoral turnout and its distribution, there is also the question of candidates’ exposure to the potential electorate, linked to politicians and party officials’ ability to canvas voters across the country. Whereas in 1994 there were distinct ‘no-go’ areas for rival electioneering by opposition parties, by 2014 commentators were noting that these were far less concrete with greater democratic space and visible competition. It was seen as a mark of South Africa’s more inclusive democratic practice and signifier of a maturing democracy. Now, as politics has become more divisive and vicious, there are ominous signs for South African democracy. There are concerns about possible electoral violence with troubling media reports of threats if Zuma’s MK party does not secure two-thirds of the vote and reported incidences of brutality and intimidation. Other parties are also implicated, with credible videos circulating on social media of MK officials being assaulted by ANC supporters, photographs of PA figures posing with powerful firearms in the Western Cape, on top of images of EFF campaign rallies with what appears to be a private militia, and use of hate speech. These concerns about violence are not hypothetical, given the searing experience of riots and looting across KwaZuluNatal and Gauteng in July 2021. This led to 354 deaths, the weakening of the Rand, and property destruction and losses of approximately R20-25 billion.[47]

This raises important questions about the independence of the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) and its willingness to implement the electoral code, to rein in inflammatory statements widely circulated on social media, and instances of electoral violence. This is on top of the logistical challenges confronting the IEC of printing and distributing ballot papers, manning polling stations, collecting and collating votes, at a time when the country continues to experience extensive rolling power cuts, and continued heavy reliance on alternative energy supplies.[48]

Money

As in any election, funding is very important. South Africa’spolitical funding system supposedly ensures transparency of donor contributions to political parties. The Political Party Funding Act formally sets out a strict framework.[49]

- Above R15 million per year from a single donor;

- From foreign governments and agencies (except for training and policy development);

- From any government department or state-owned entity.

On the evidence of recent elections, it is worth asking how closely is this observed and enforced? Party accounts are only presented a considerable time after the ballot. Until very recently, the ANC was staring at bankruptcy. Its financial difficulties were widely reported, together with its lamentable track record for non-payment. Its debt to Ezulweni Investments, a KwaZuluNatal marketing company, for services during the 2019 election campaign, spiralled to approximately R150million.

External funding sources remain important for the ANC. There was a great deal of speculative chatter on social media that the government’s case in the ICJ against Israel was funded by a large Iranian or Qatari donation; however, this remains unproven. (Similarly, theaccusation that this was mainly done to placate black voters,[50] and the poor in particular, is wide of the mark. There has been a longstanding Muslim influence on South African foreign policy, and determined support of the Palestinian cause, dating back to Aziz Pahad’s tenure as Deputy Foreign Minister in the 1990s.) There have also been rumours that vital funds may have come from the Western sanction Russian oligarch, Viktor Vekselberg, linked to ANC donor United Manganese of the Kalahari (UMK).[51] According to Russia expert Professor Irina Filatova, the Kremlin is keen that ANC should stay in power; however, the Putin government equally would be prepared to work with Zuma, or the EFF. However, in her view, the Russian government’s preference is the ANC.

Furthermore, campaigning is an expensive business – rally freebies, and transport of loud supporters – and the potential rewards are considerable. But indications are the potential voters are savvy, accepting the handouts but not necessarily delivering the votes. It is a common misconception that election rally handouts significantly influence voters’ preferences.[52]

Outcome

What the election holds in store for South Africans, and their friends and allies around the world, is impossible to predict. Much depends on turnout and the ability of parties to mobilise their supporters. In the past the nation has repeatedly reached the edge of despair. One only needs recall the disastrous impact of the Mfecane, the Anglo-South African war, the Rand Revolt, the Apartheid system, the Sharpeville massacre, the state sponsored murders, the Marikana massacre and the riots following the arrest of Jacob Zuma in 2021 to see how serious the situation can become. Yet South Africans continue to get by and to innovate and even prosper despite having intermittent water supplies, incessant blackouts and a collapsing infrastructure. Despair is a state of mind that its people cannot afford and certainly do not deserve. The Independent Election Commission has generally overseen free and fair elections and we must hope and anticipate that they will do the same in 2024. We must all await the verdict of the people, as they decide their future at the ballot box.

[1] sue.onslow@kcl.ac.uk . martin.plaut10@gmail.com

[2] https://www.news24.com/news24/politics/political-parties/mbalula-defends-anc-candidate-selection-process-says-party-put-forward-its-best-20240311

[3] https://www.news24.com/news24/investigations/high-roller-zumas-ex-son-in-law-in-high-court-battle-over-his-bentley-ferrari-rolls-royce-20240308

[4] https://www.biznews.com/sarenewal/2024/03/11/brenthurst-foundation-voter-survey

[5] https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/05/03/in-south-africa-racial-divisions-and-pessimism-over-democracy-loom-over-elections/ft_19-05-03_southafrica_southafricanswithunfavorableviews_2/

[6] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-04/south-african-mining-profits-slump-by-almost-half-fin24-says

[7] https://www.cde.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/The-Silent-Crisis-South-Africas-failing-education-system.pdf

[8] https://www.news24.com/citypress/politics/the-anc-is-on-the-brink-of-losing-more-metros-20220814

[9] https://www.thebrenthurstfoundation.org/surveys/survey-of-south-african-voter-opinion-march-2024/

[10] https://www.news24.com/citypress/voices/dumisani-hlophe-coalition-governments-pose-a-risk-to-service-delivery-20221008

[11] https://www.biznews.com/leadership/2024/03/10/election24-solly-moeng

[12] https://www.theafricareport.com/327261/south-africa-councillors-political-murders-at-crisis-level-as-2024-looms/

[13] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-01-08-zuma-will-have-to-be-kicked-out-of-anc-but-mechanics-will-matter/

[14] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-01-08-it-was-a-lie-mbalula-admits-anc-tricked-parliament-to-protect-zuma-in-nkandla-fire-pool-debacle/

[15] eCNA.com news report, 1 March 2024.

[16] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KN?end=2022&locations=ZA&start=2010&view=chart

[17] https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/709568/how-much-politicians-get-paid-vs-the-average-taxpayer-in-south-africa/

[18] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=ZA

[19] https://www.gov.za/services/services-residents/social-benefits/old-age-pension

[20] Omry Makgoale, Daily Maverick, 10 March 2024.

[21] https://www.iol.co.za/news/anc-uses-sassa-in-a-new-voting-advert-and-x-users-are-not-having-it-1af89895-f1d4-436b-9d46-8af4912f4151

[22] https://www.uj.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/factors-determining-voter-choice-_-report-_-may-2021-_-web_final.pdf

[23] https://www.da.org.za/2024/01/social-grants-will-disappear-if-the-corrupt-anc-is-re-elected

[24] https://www.eisa.org/pdf/JAE15.1Sadie.pdf

[25] The current Child Support Grant is R510 per month. Relatives caring for an orphaned child can apply for and receive the Child Support Grant Top-Up of R720 per child per month. SASSA online services, Child Support Grant Information

[26] https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9953/CBP-9953.pdf

[27] On 29 February 2024, days after presenting the party’s manifesto, Robert Jardine announced that this new political movement would not contest the elections. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HENurioCvdA

[28] https://www.citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/politics/anc-mantashe-pre-election-apartheid-party-conspiracy/

[29] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-03-11-battle-for-the-future-of-media-daily-mavericks-submission-to-the-competition-commission/?utm_source=Sailthru

[30] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-11-07-the-media-just-about-got-election-coverage-right-but-challenges-remain/

[31] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-11-07-the-media-just-about-got-election-coverage-right-but-challenges-remain/

[32] Daily newspaper consumption by brand December 2023, Statista

[33] https://www.statista.com/statistics/685134/south-africa-digital-population/

[34] https://www.statista.com/statistics/1316431/social-media-usage-reasons-in-south-africa/

[35] William Bird, https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/2024-elections-credibility-of-news-threatened-ahead-of-vote/

[36] Sue Onslow: Social media’s impact on political discourse in South Africa (LSE IDEAS, 2021).

[37] https://www.elections.org.za/pw/Voter/Report-Electoral-Fraud. The IEC advertised this service in the 2021 municipal elections .

[38] Omry Makgoale, Daily Maverick, 10 March 2024. ‘The State Capture inquiry report delivered by Chief Justice Raymond Zondo implicated more than 90 ANC leaders and members in wrongdoing. These include Gwede Mantashe, the ANC national chairperson; Zizi Kodwa, the minister of arts and culture; and Thabang Makwetla, the deputy defence minister’.

[39] See https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/constitution-republic-south-africa-1996-chapter-4-parliament-07-feb-1997#74

[40] https://static.pmg.org.za/docs/Van-Zyl-Slabbert-Commission-on-Electoral-Reform-Report-2003.pdf

[41] https://www.afrobarometer.org/publication/south-africas-ruling-party-is-performing-dismally-but-a-flawed-opposition-keeps-it-in-power/

[42] South Africans hold negative views about immigrants for a range of reasons. See https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/05/03/in-south-africa-racial-divisions-and-pessimism-over-democracy-loom-over-elections/ft_19-05-03_southafrica_mostsouthafricans_2/

[43] https://www.elections.org.za/pw/StatsData/Voter-Registration-Statistics

[44] https://www.elections.org.za/pw/StatsData/Voter-Registration-Statistics

[45] Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny, Shannon van Wyk-Khosa and Joseph Asunka, AD734, More Educated, Less Employed, still unheard in policy and development, Afrobarometer, 15 November 2023

[46] https://www.afrobarometer.org/publication/south-africas-ruling-party-is-performing-dismally-but-a-flawed-opposition-keeps-it-in-power/

[47] This civil unrest was both stimulated and coordinated through social media. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/social-media-vigilantism-is-alive-and-trending-in-south-africa

[48] There has been a progressive ‘privatization by incompetence’, with consumers switching to alternative supplies of solar and wind energy where possible. This has been matched at national level by President Ramaphosa’s decision in 2022 to remove the previous lock on ESKOM’s national electricity production by coal producers, by lifting limits on the amount of power from private electricity generators. David Pilling, The Financial Times, 12 March 2024.

[49] https://www.elections.org.za/pw/Party-Funding/Private-Funding-Of-Political-Parties

[50] https://www.politicsweb.co.za/opinion/the-anc-is-going-for-broke

[51] https://www.biznews.com/interviews/2024/02/20/anc-moscow-plotting-against-west-navalny-died

[52] https://www.afrobarometer.org/articles/ai-and-technology-are-not-a-panacea-for-voter-apathy-afrobarometer-surveys-director-tells-political-campaigns-expo/