Readers may recall that the Norwegian Parliament has called on its government to act against transnational repression of Eritreans and other diasporas living in Norway.

But Norway is by no means the only country afflicted with this problem. Below are two reports detailing the repression in Germany.

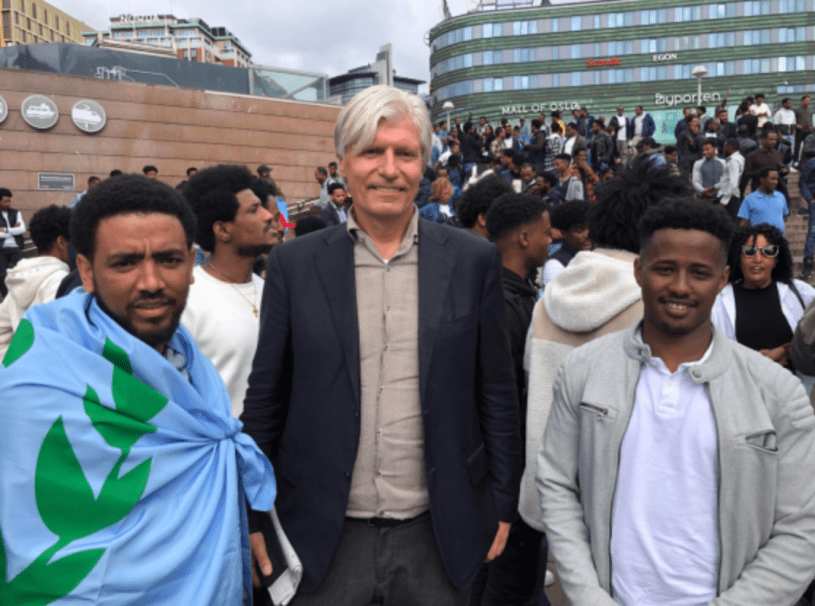

Martin

Source: Freedom House

Germany: Transnational Repression Host Country Case Study

PDF Download Policy Recommendations

Germany hosts one of the largest refugee populations in the world and at least a dozen governments target their nationals residing in Germany, including the most prolific offenders like Turkey and China.

Germany hosts one of the largest refugee populations in the world and at least a dozen1 governments target their nationals residing in Germany, including the most prolific offenders like Turkey and China. The government has demonstrated some awareness of and resilience to the phenomenon. However, a more robust German response is hampered by the security apparatus’ focus on extremism and inconsistencies in protection schemes for refugees and asylum seekers, including policies that identify them as a potential source of threats to Germany rather than as potential victims of foreign repression. Incorporating the risk of transnational repression into Germany’s national security framework, prioritizing human rights in foreign policy, and small, practical changes to the migration bureaucracy would position Germany as a leader in responding to transnational repression.

Best practices in Germany’s response to transnational repression:

- Intelligence and law enforcement bodies coordinate to warn and protect targeted individuals.

- Expulsion of diplomats following incidents of transnational repression creates accountability.

- Foreign assistance requests, including for extradition and arrest, require oversight and consultation among multiple government ministries.

- The government invests resources into a migration system that grants legal protection to refugees, including political exiles.

Introduction

In December 2021, a German court convicted a former colonel in the Russian intelligence service, Vadim Krasikov, of the 2019 daylight assassination of Zelmikhan Khangoshvili, an ethnic Chechen asylum seeker and Georgian citizen living in Berlin. The judge in the case explicitly identified the Kremlin as behind the crime, stating that “in June 2019 at the latest, state organs of the central government of the Russian Federation took the decision to liquidate…Khangoshvili in Berlin.”2 Even before the verdict was rendered, suspicions about Russia’s involvement led Germany to expel two Russian diplomats,3 and Krasikov’s conviction was followed by the expulsion of two more. The German foreign minister called the assassination a “grave breach of German law and the sovereignty of the Federal Republic of Germany.”4

The strong response by the German state to Khangoshvili’s murder is relatively unique. Numerous other governments including those of Rwanda, Turkey, Egypt, Vietnam, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and China, have used tactics of transnational repression to target individuals residing in Germany.5 However, most incidents have not triggered criminal proceedings or diplomatic expulsions—forceful responses have instead been reserved for high-profile, violent acts of transnational repression.

The German government demonstrates high levels of awareness of transnational repression through government reports, offering police protection to at-risk individuals, and responses to high-profile attacks as in the case of Khangoshvili. However, the government’s policy responses are inconsistent and have notable gaps. Germany’s national security framework does not adequately address foreign states’ threats to the human rights of individuals residing in Germany. Instead, a heavy focus on preventing terrorism and radicalization, as well as the prioritization of conflicting foreign policy goals, hamper the government’s ability to address transnational repression. In the migration sphere, efficiency trade-offs, such as housing asylum seekers of a specific nationality together, inadvertently put people at risk. Responses to the migration crisis of 2015—including scaling up translation capacity without implementing safeguards against surveillance by translators, and increased use of temporary forms of migrant protection—further exacerbate the system’s vulnerabilities.

Security

Transnational repression is a threat to personal safety and an infringement on the rights guaranteed by the German constitution. Germany’s Foreign Intelligence Service (BND) and Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV) are responsible for issues related to security at the national level, though the country’s federal structure requires a degree of coordination with subnational offices and law enforcement. The BfV recognizes that Germany is a “target for a wide range of political espionage.”6 Authorities are consequently attuned to clandestine activities by foreign states. However, they overlook opportunities to address the specific threat posed by transnational repression in favor of other national security and foreign policy priorities. Acts of transnational repression are frequently folded into responses to terrorism and radicalization, which obscures their impact and distracts from creating appropriate policy responses.

Government awareness and national security priorities

While certain German authorities demonstrate a relatively high level of awareness of the of tactics transnational repression, the government fails to recognize it as a distinct phenomenon. In a 2020 interview, BfV president Thomas Haldenwang suggested that the Russian government’s assassination of Khangoshvili and other similar attacks are intended to have a deterrent effect on diaspora. He noted that foreign governments are increasingly interested in diasporas in Germany, citing Turkey and Iran as examples.7 Similarly, Bruno Kahl, head of the BND, described extraterritorial assassinations in Germany, including the Khangoshvili murder, as part of the perpetrator states’ foreign policy.8 The Khangoshvili murder also precipitated numerous rounds of inquiry from members of parliament, including into the nature of the Russian government’s cooperation with German investigations.9

The BfV’s 2020 report on the protection of the constitution identified Russia, China, Iran, and Turkey as engaging in activities that constitute transnational repression, including surveillance of dissidents. The report does not address transnational repression as a unique phenomenon; examples are instead included in a broad section about activities by foreign powers that threaten the German state’s security, including counterintelligence, cyberattacks, intellectual property theft, and propaganda. The section only addresses traditionally adversarial governments, namely Russia, China, Iran, and Turkey, and describes the Khangoshvili assassination as an act of state-sponsored terrorism.10 A previous version of the report also identified Egyptians in Germany as potential targets of Egyptian intelligence.11

Viewing tactics of transnational repression as a subset of existing national security priorities—specifically, terrorism and radicalization—rather than as a standalone threat to safety and human rights limits the German government’s ability to recognize potential victims. Germany’s current approach to transnational repression is best exemplified by a BfV 2018 brochure designed for refugees in German titled, “How can I identify extremists and members of foreign secret services within my environment?” The document notes the presence of foreign operatives within Germany who may surveil or intimidate refugees and encourages people to report suspicious activity to refugee accommodation centers, local police, or the BfV. However, because the brochure is focused on radicalization, terrorism, and activities by extremist groups, it counterproductively identifies refugees as a potential source of threats to Germany, rather than as potential victims of foreign repression.

In 2017, the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DİTİB) admitted that some of its imams had facilitated transnational repression by surveilling individuals suspected of being connected to the movement of religious leader Fethullah Gülen, at the behest of the Turkish government. These allegations precipitated an investigation by the federal prosecutor’s office and contributed to the government’s eventual decision to no longer fund projects with DİTİB.12 However, the decision was also a response to multiple DİTİB-related controversies otherwise unrelated to transnational repression, and again reflected the government’s broader approach to terrorism and extremism. Similarly, the German government has taken greater interest in the foreign funding of mosques in recent years, as it views foreign funding as a risk factor for radicalization.13 In 2018, Germany’s foreign ministry began requesting that Gulf states register donations or other contributions to mosques in Germany.

Conflating defense against radicalization with protection for individuals recasts potential victims as security threats, which can contribute to Islamophobia. Counterproductively, this approach also leaves people of Muslim origin, who are among the most vulnerable to transnational repression,14 at even greater risk of harm.

Foreign and domestic information sharing

German authorities have at times alerted individuals believed to be under surveillance by foreign states and provided police protection to people under threat, though the processes triggering these actions and the frequency of their use are unclear.15 Such alerts rely on extensive information sharing within the government, and the complex coordination required by Germany’s federal structure introduces room for error.

However, intelligence sharing and cooperation between governments is a risk factor for transnational repression. Publicly available reporting provides some insight into information sharing and protection in several cases related to Turkey’s transnational repression. The Turkish government is one of the most prolific perpetrators of transnational repression globally and is active in Germany. It primarily targets people allegedly affiliated with the Gülen movement, which President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan holds responsible for the 2016 coup attempt and labels as a terrorist organization.16 Two Turkish journalists in exile report that German police continuously evaluate their safety and adjust the level of protection they receive accordingly.17

In February 2017, Turkish intelligence services requested German cooperation in their surveillance of hundreds of Turks living in Germany who were allegedly supporters of the Gülen movement. Turkish authorities shared detailed information with the BND leadership, including names, addresses, phone numbers, and clandestinely acquired photographs.18 Despite Turkey’s efforts, Germany’s intelligence services do not view Gülen supporters as terrorists, and members of government at multiple levels expressed alarm about surveillance occurring on German soil. In an example of successful coordination across multiple levels of government, the BND alerted numerous relevant government offices, including the BfV, the federal criminal police office, and the federal prosecutor general of the Turkish request. Local offices, including state police, were tasked with alerting the affected individuals that they were being surveilled and might face reprisals if they travel to Turkey.

Roughly two thirds of physical incidents of transnational repression involve cooperation between origin and host states, or cooption—origin states using the host state’s institutions to reach an individual, often by leveraging allegations of terrorist activity) and cooperation between origin and host states.19 Authorities’ decision not to cooperate with Turkish intelligence services’ requests about Gülen supporters, and instead to protect the named individuals, suggests that German awareness of transnational repression and information sharing across federal and state-level authorities translates to resilience against cooption in certain cases.

Accountability and foreign policy

Germany’s efforts to impose accountability for transnational repression are inconsistent. As in the Khangoshvili case, some attacks have been dealt with through the German judicial system. For example, the 2017 state-sponsored kidnapping of a Vietnamese asylum seeker, Trinh Xuân Thanh, and his companion resulted in a multiyear prison sentence for a Vietnamese man who assisted in the abduction.20

Over the last 10 years, Germany has expelled diplomats in relation to three instances of transnational repression that occurred within Germany. A total of four Russian diplomats were expelled over the course of the Khangoshvili affair,21 and two Vietnamese diplomats were expelled in the aftermath of Thanh’s abduction.22 The third was in 2012, when authorities ousted four Syrian diplomats in relation to surveillance of Syrians in Germany.23

Beyond expelling diplomats, itself a rare move, Germany’s existing accountability mechanisms are limited. Germany does not apply sanctions unilaterally, but it adheres to UN and EU sanctions and has participated in multilateral responses to transnational repression elsewhere in Europe.24 In September 2020, the Green Party proposed that Germany adopt an individual sanction mechanism, similar to the Global Magnitsky Act, that would allow authorities to impose targeted sanctions such as visa bans and asset freezes against individuals found to have committed human rights violations.25 The resolution used the murder of Saudi journalist and dissident Jamal Khashoggi as a justification for the need for such sanctions and advocated for similar measures at the EU level. In 2021, Germany was a strong proponent of EU-wide sanctions in response to the Belarusian hijacking of a passenger plane in order to arrest exiled activist Roman Protasevich.26 In 2018, in coordination with other European countries and the United States, Germany expelled four Russian diplomats in response to the Russian poisoning of former intelligence officer Sergei Skripal in England.27

German support for multilateral sanctions in response to attacks that occurred outside of Germany is notable because transnational repression within the country has not elicited a united European response, nor any lasting change to Germany’s bilateral relations. The Khangoshvili case does not appear to have impacted Germany’s relationship with Russia more broadly, despite condemnations by government officials. German chancellor Olaf Scholz called for a relationship reset with Russia soon after taking office at the end of 2021 and within weeks of the verdict in the Khangoshvili case.28 Though later overshadowed by Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the timing of the initial effort at reconciliation underscored how transnational repression can be deprioritized in relation to other foreign policy considerations.

Germany’s new foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock, has said she will pursue a “values-based foreign policy,”29 and the governing agreement between coalition parties pledged support to civil society and human rights defenders “even in the event of cross-border persecution.”30 If it comes to fruition, the new approach could bring increased accountability and attention to transnational repression.

Migration

Germany is the fifth-largest host state for refugees in the world, with 1.14 million refugees and over 295,000 asylum seekers.31 Syrians account for approximately half of all refugees in Germany, followed by people from Afghanistan and Iraq. In addition to Syrians, Germany also hosts sizeable populations of diasporas vulnerable to transnational repression, including Turks, Iranians, and Eritreans.32

With so many foreign residents from targeted populations living in Germany, transnational repression is entangled with the country’s migration structures. The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), which coordinates the migration system, is undergirded by extensive bureaucratic processes and structures, some of which inadvertently create vulnerabilities to transnational repression. Policy responses to rising numbers of asylum seekers have increased the potential exposure to targeting by a foreign state. Nevertheless, Germany has laws and oversight mechanisms that help protect against origin states coopting German institutions to target their nationals.

Legacy of the German response to the refugee crisis

Since 2015–16, over a million people, largely from Syria, applied for asylum in Germany. The country accepted more refugees than it was required to under EU agreements, but the issue of migration became increasingly contentious as nationalist and other segments of society pushed back on pro-migrant policy, and the government eventually walked back some of the more generous policies.33 Living in Germany generally offers refugees more protection from transnational repression than if they remained in states that have a track record of willfully violating the right to asylum and cooperating with origin states. However, Germany’s response to the refugee crisis underscores the risks associated with bureaucratic efficiency.

BAMF hired thousands of new interpreters to accommodate the spike in asylum applications.34 Freelance translators are required to be in good legal standing and take various “reliability” tests, but civil society organizations and asylum seekers have long called their qualifications into doubt35 and numerous reports have pointed to interpreters acting in the interest of the asylum seeker’s origin state.36

Interpreters have access to deeply personal information of vulnerable people. Information gathered by translators and shared with origin governments can result in further intimidation and surveillance, smear campaigns, and harm to family members and associates still residing in the origin country. Turkish asylum seekers have alleged that interpreters and other BAMF officials shared their personal information with Turkish government-affiliated media, leading to smear campaigns and the publication of sensitive information, including their location, by those outlets. Others from Turkey and elsewhere report harassment and intimidation by the translators. Eritrean and Turkish translators have allegedly altered testimonies and intimidated asylum seekers in Germany during the asylum interview process.37 Manipulating interviews can result in denial of asylum applications.

Over the years, numerous German officials have claimed that interpreters do not engage in surveillance, harassment, or intimidation. However, some politicians called for more extensive vetting of interpreters in response to such reports of misconduct. In response to a range of concerns about interpreters, BAMF introduced new training programs, more stringent language requirements, and a code of conduct in 2017. BAMF also introduced a complaint-management system.38 Most of these reforms address concerns about translators’ qualifications, but they do not address the risk that translators may act on behalf of foreign states. The complaint system provides an opportunity for recourse if intimidation or harassment occurs, but it does not prevent harm during initial interactions and it places the burden of assessing translators on already vulnerable individuals, rather than on the German state.

A second policy problem stemming from Germany’s response to the influx of refugees is an increased use of subsidiary protection, a category that does not grant refugee or asylum-seeker status but allows an individual to remain in the country in recognition that they may face serious harm upon returning to their home country. In 2015, four percent of individuals who received protection were given subsidiary status. That percentage jumped to 35 percent in 2016, peaked at 37 in 2017, and has since remained elevated at approximately 30 percent.39 Asylum seekers from Syria and Eritrea, both populations vulnerable to transnational repression, are given subsidiary protection at high rates.

Subsidiary protection provides less security than refugee status, leaving recipients more vulnerable to targeting by their origin state. Its temporary nature requires more frequent renewal than refugee status, creating an administrative burden and long-term insecurity.40 Differences in documentation leave recipients of subsidiary protections reliant on their home-country embassies for passport renewal and other documents, such as marriage licenses.41 Continued contact with embassies is a risk factor for surveillance, intimidation, and other harms. Subsidiary protection does not include the right to family reunification, unlike refugee and asylum status, exposing recipients to coercion by proxy.

Refugee reception centers

Refugee reception centers exemplify the tradeoff between efficiency and protection for at-risk individuals The BAMF divides asylum seekers among the 16 federal states, with a percentage of asylum seekers assigned to each state.42 Asylum seekers are placed among the states on the basis of their country of origin, with each refugee reception center responsible for refugees from a specific country or countries. For example, Thai asylum seekers are divided among two centers in North Rhine-Westphalia and two in Lower Saxony.43 Asylum seekers live in the provided housing for up to six months, or until their application is decided.44

The centers are an efficient means of providing goods and services to people in the asylum process. However, that same centralization inadvertently creates risks for people vulnerable to transnational repression. First, publicly listing which refugee welcome centers house populations from which country make them potential targets of surveillance, intimidation, and attack. For example, supporters of the Eritrean government visited refugee housing to urge Eritreans to pay the diaspora tax—a percentage of earnings the Eritrean government requires all Eritreans abroad to pay, regardless of their status.45 A Saudi woman reported intimidating visits from anonymous men she believed were government loyalists.46

Second, living among others from the same origin state creates opportunities for transnational repression to occur within that group of asylum seekers.47 In one example, a Saudi asylum seeker learned that investigators in Saudi Arabia were questioning her friends about specific details of her life in Germany. The details they knew about her whereabouts and activities were so specific she worried that someone she interacted with while living in the provided refugee housing was reporting information to Saudi authorities.48

A 2017 guide on extremism and secret service activities published by the BfV for refugee aid workers notes that refugees who acted against the government in their home state are potential targets of their origin state’s intelligence operatives in Germany. It warns that foreign intelligence officers may pose as refugees to surveil fellow refugees and interfere with their efforts to gain asylum status. The document also notes that surveillance can result in harm to their family members who remain in the origin country.49

While the guide emphasizes the importance of identifying these problems, it does not offer harm-mitigation solutions beyond being alert to these issues throughout normal asylum processes. It also frames recruitment of refugees to act on behalf of the foreign state as one of the goals of espionage, which is a separate issue from transnational repression and frames targeted refugees as potential security threats, rather than victims of ongoing state violence.

Promising oversight

In general, German authorities treat information about individuals received from foreign states, including through Interpol, with well-warranted skepticism. Authorities generally do not rely on information supplied by origin countries when reviewing asylum claims. Extradition requests, requests for legal assistance, and arrest warrants are processed at the federal level, in consultation with multiple government bodies, before dispersal to relevant law enforcement. The German Federal Ministry of Justice (BfJ), the Federal Foreign Office, the Federal Criminal Police Office, and other government authorities may be involved in the review process, which includes determining whether there are legal or political reasons not to comply with the request.50 The Act on International Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters has numerous restrictions on extradition, including when the request is based on an alleged political offence, when there is a risk that the individual will be transferred to a third state, and when the individual may be subject to capital punishment. In 2018, the German government halted deportations of Uyghurs and other Muslims to China due to the Chinese Communist Party’s persecution of these groups.51

Oversight and protections against unlawful deportation are particularly necessary because Germany, both bilaterally and as part of the EU, has return-and-readmission agreements with numerous states known to engage in transnational repression, including Azerbaijan, Belarus, Russia, Pakistan, and Turkey.52

Despite these safeguards—and efforts by the government to limit Interpol abuse, such as reviewing the coordination between relevant ministries—targets of transnational repression in Germany have been subject to detention and unlawful deportation.53 In 2017, intervention by the Foreign Office prevented a Rwandan from being extradited at the Rwandan government’s request, but not until he had already spent time in detention.54 Similarly, in 2015 an Egyptian journalist was detained on the basis of an Egyptian extradition request for two days before being released.55 In 2017 and 2018, two Chechen asylum seekers were extradited to Russia despite a high likelihood of poor and politicized treatment.56 Improved coordination and awareness of transnational repression in oversight processes would prevent similar incidents in the future.

Recommendations for the German government:

- Raise awareness of transnational repression within the government. Develop trainings for all officials who engage with vulnerable populations or may encounter incidents of transnational repression in their work, including members of law enforcement, migration officials, and foreign affairs officials, including diplomatic staff.

- Update national security priorities to recognize that threats to an individual’s human rights by a foreign state are also a threat to German’s institutions and agencies.

- Implement a review of existing laws and policies to develop and improve mechanisms for ensuring the accountability of foreign states perpetrating transnational repression.

- Identify and document transnational repression as a distinct problem, including in the BfV’s annual report on the protection of the constitution and Federal Foreign Office’s human rights reports.57

- Ensure that protections and responses to transnational repression treat targeted individuals as potential victims, rather than as security threats. Responses to transnational repression should be separate from policies that address radicalization, terrorism, or recruitment by foreign intelligence services.

- Reduce reliance on temporary forms of protection for asylum seekers and return to a norm of granting full refugee status.

- Screen for vulnerability to transnational repression early in the immigration and asylum process. Provide high-risk individuals with additional protection throughout the process, such as accommodation outside of a refugee reception center and digital security support.

Footnotes

- 1Countries that have committed acts of transnational repression in Germany include Rwanda, Turkey, Egypt, Vietnam, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, China, Iran, Syria, Russia, and Eritrea.

- 2//www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/12/15/germany-russia-chechen-murder-b….

- 3//www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53091298; “Berlin Murder: Germany Expels Two Russian Diplomats,” British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), December 4, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50659179.

- 4//apnews.com/article/europe-russia-germany-foreign-policy-moscow-00406c5409443089310c725441d30915.

- 5Amnesty International, “Amnesty International Report 2017/18 – Rwanda,” February 22, 2018, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5a99387aa.html; Alexander Fröhlich, “Erdogan-Kritiker Werden Eingeschüchtert – In Berlin” [Erdogan Critics Are Intimidated – In Berlin], Der Tagesspiegel, October 10, 2018, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/polizeischutz-fuer-can-duendar-erdog…; “Germany Frees Detained Al Jazeera Journalist Ahmed Mansour,” Middle East Eye, June 23, 2015, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/germany-frees-detained-al-jazeera-jo…; Bettina Borgfeld, “German Court Jails Vietnamese Man For Helping Kidnap Ex-Executive,” Reuters, July 25, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-vietnam/german-court-jails-v…; Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Harassed, Imprisoned, Exiled,” October 20, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/20/harassed-imprisoned-exiled/azerba…; HRW, “Tajikistan: Stop Persecuting Opposition Families,” July 18, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/18/tajikistan-stop-persecuting-opposit…; Amnesty International, “Bahrain: ‘No One Can Protect You’: Bahrain’s Year Of Crushing Dissent,” September 7, 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde11/6790/2017/en/; Sarah Aziza, “The Saudi Government’s Global Campaign to Silence Its Critics,” The New Yorker, January 15, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-saudi-governments-global-ca…; Amnesty International, “Nowhere Feels Safe,” February 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2020/02/china-uyghurs-abroad….

- 6//www.verfassungsschutz.de/SharedDocs/publikationen/EN/reports-on-the-pro….

- 7//www.zeit.de/2020/42/thomas-haldenwang-spionage-deutschland-coronavirus-….

- 8//www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/berlin-ist-hauptstadt-der-spione-das-sind-d….

- 9//dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/213/1921318.pdf

- 10//www.verfassungsschutz.de/SharedDocs/publikationen/EN/reports-on-the-pro….

- 11//www.dw.com/en/germany-charges-egyptian-with-spying-while-working-in-mer….

- 12//www.dw.com/en/germany-cuts-funding-to-largest-turkish-islamic-organizat…; Chase Winter, “Turkish Islamic Organization DITIB Admits Preachers Spied In Germany,” Deutsche Welle, January 12, 2017, https://www.dw.com/en/turkish-islamic-organization-ditib-admits-preache…; Hasnain Kazim, “Turkey

- 13//www.dw.com/en/germany-to-curb-mosque-funding-from-gulf-states/a-46882682; Kait Bolongaro, “Germany Mulls Mosque Tax To Curb Foreign Funding Fears,” Politico, May 12, 2019, https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-mulls-mosque-tax-to-curb-foreig….

- 14//freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Complete_FH_TransnationalRepressionReport2021_rev020221.pdf.

- 15//www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/polizeischutz-fuer-can-duendar-erdogan-kriti…; Attila Mong, “For Turkish Journalists in Berlin Exile, Threats Remain, But in Different Forms,” Committee to Protect Journalists, July 18, 2019, https://cpj.org/2019/07/for-turkish-journalists-in-berlin-exile-threats…; “Geheim Darf Das Ohne Kenntnis Unseres Staates Nicht Geschehen” [This Must Not Happen Secretly Without the Knowledge of Our State], Deutschlandfunk, March 28, 2017, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/tuerkische-spionage-geheim-darf-das-ohne….

- 16//freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/turkey.

- 17//cpj.org/2019/07/for-turkish-journalists-in-berlin-exile-threats-re/.

- 18//www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/exklusiv-tuerken-in-deutschland-werden-auss….

- 19//freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Complete_FH_TransnationalRepressionReport2021_rev020221.pdf.

- 20//www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-vietnam/german-court-jails-vietnames….

- 21//apnews.com/article/europe-russia-germany-foreign-policy-moscow-00406c5409443089310c725441d30915.

- 22//www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-vietnam/germany-expels-second-vietna…; German Bundestag, “Auf Die Kleine Anfrage Der Abgeordneten Sevim Dağdelen, Heike Hänsel, Dr. André Hahn, Weiterer Abgeordneter Und Der Fraktion,” [Question From Deputies Sevim Dağdelen, Heike Hänsen, Dr. André Hahn], July 28, 2020, https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/213/1921318.pdf.

- 23//www.nytimes.com/2012/02/10/world/europe/germany-expels-four-syrian-dipl…; German Bundestag, “Auf Die Kleine Anfrage Der Abgeordneten Sevim Dağdelen, Heike Hänsel, Dr. André Hahn, Weiterer Abgeordneter Und Der Fraktion [Question from Deputies Sevim Dağdelen, Heike Hänsen, Dr. André Hahn].

- 24//iclg.com/practice-areas/sanctions/germany, accessed May 9, 2022.

- 25//dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/213/1921318.pdf.

- 26//www.thetimes.co.uk/article/eu-punishes-belarus-for-forced-landing-of-ro…; Hans Von Der Burchard, “Germany Threatens Sanctions ‘Spiral’ Unless Belarus Frees Prisoners,” Politico, May 27, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-warns-alexander-lukashenko-bela…; Hans Von Der Burchard, “Merkel Demands Immediate Release Of Belarus Activist And Partner,” Politico, May 24, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/angela-merkel-calls-for-eu-sanctions-ag….

- 27//www.dw.com/en/germany-other-countries-expel-russian-diplomats-over-skri… ; German Bundestag, “Auf Die Kleine Anfrage Der Abgeordneten Sevim Dağdelen, Heike Hänsel, Dr. André Hahn, Weiterer Abgeordneter Und Der Fraktion [Question From Deputies Sevim Dağdelen, Heike Hänsen, Dr. André Hahn], July 28, 2020, https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/213/1921318.pdf

- 28//www.voanews.com/a/smaller-european-nations-uneasy-as-germany-scholz-pla….

- 29//www.justsecurity.org/79618/how-germanys-new-government-might-pursue-its….

- 30Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschland (SPD), Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen Und Den Freien Demokraten (FDP) [German Social Democratic Party (SPD), Alliance 90/The Greens, and the Free Democratic Party (FDP)], “Mehr Fortschritt Wagen: Bündnis Für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit Und Nachhaltigkeit” [Dare More Progress: Alliance For Liberty, Justice And Sustainability], p. 145, https://cms.gruene.de/uploads/documents/Koalitionsvertrag-SPD-GRUENE-FD….

- 31//www.unhcr.org/dach/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2021/03/Bi-annual-fact-s….

- 32//asylumineurope.org/reports/country/germany/statistics/.

- 33//www.dw.com/en/five-years-on-how-germanys-refugee-policy-has-fared/a-546…; Freedom House, “Freedom in the World, 2021: Germany,” https://freedomhouse.org/country/germany/freedom-world/2021.

- 34//www.infomigrants.net/fr/post/6160/asylum-requests-a-good-interpreter-ca….

- 35//www.dw.com/en/turkey-spies-betraying-asylum-seekers-in-german-immigrati… ; Holly Young, “Asylum Requests: A Good Interpreter Can Make All The Difference.”

- 36//asylumineurope.org/reports/country/germany/asylum-procedure/procedures/regular-procedure/.

- 37//www.dw.com/en/eritrean-translators-intimidating-refugees-in-germany/a-1… ; Nicole Hirt, “The Long Arm of the Regime – Eritrea and Its Diaspora” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung [Federal Agency for Civic Education], April 16, 2020, https://m.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/laenderprofile/english-version-…; Ben Knight, “Turkey Spies Betraying Asylum Seekers in German Immigration Offices,” Deustche Welle, October 16, 2017, https://www.dw.com/en/turkey-spies-betraying-asylum-seekers-in-german-i… ; Elaine Allaby, “Are Eritrea Government Spies Posing As Refugee Interpreters?” Aljazeera, February 26, 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2018/2/26/are-eritrea-government-spi… ; Mohamed Amjahid und Paul Middelhoff, “Feind Hört Mit” [The Enemy Hears With], Zeit Online, November 27, 2017, https://www.zeit.de/2017/48/bamf-asylbewerber-dolmetscher-bedrohung-bes…; Nate Schenkkan and Isabel Linzer, Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach: The Global Scale and Scope of Transnational Repression, (Washington, DC: Freedom House, February 2021), https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Complete_FH_Transn….

- 38//www.dw.com/en/turkey-spies-betraying-asylum-seekers-in-german-immigrati…; Paula Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, “Regular Procedure: Germany,” Asylum Information Database, last modified April 21, 2022, https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/germany/asylum-procedure/pro….

- 391705/40560 in 2015, 153,965/433905 in 2016, 98,065/261620 in 2017, 25030/75940 in 2018, 19415/70320 in 2019, 18,950/62470 as of 2020. See “Asylum” Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/migration-asylum/asylum/database.

- 40//www.bamf.de/EN/Themen/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/AblaufAsylverfahrens/Schut….

- 41BAMF, “Subsidiary Protection.” ; Marion MacGregor, “What Is the Difference Between Refugee Status And Subsidiary Protection?” InfoMigrants, June 19, 2021, https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/33060/what-is-the-difference-betwe….

- 42//www.bamf.de/EN/Themen/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/AblaufAsylverfahrens/Erstv….

- 43//www.nds-fluerat.org/48797/aktuelles/easy-liste-zustaendigkeiten-der-aus…; Bullseye Locations, “Germany State Codes,” last modified April 23, 2022, https://kb.bullseyelocations.com/article/58-germany-state-codes.

- 44//www.bamf.de/EN/Themen/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/AblaufAsylverfahrens/Erstv….

- 45//m.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/laenderprofile/english-version-country-profiles/305657/eritrea.

- 46//www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-saudi-governments-global-campaign-t….

- 47//www.dw.com/de/bedrohte-saudische-frauen-in-deutschland-wir-werden-dich-….

- 48//www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-saudi-governments-global-campaign-t….

- 49Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), “Wie Erkenne Ich Extremistische Und Geheimdienstliche Aktivitäten?” [How Do I Recognize Extremist and Secret Service Activities?], August 2017, https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/SharedDocs/publikationen/DE/allgemein/….

- 50//www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_irg/index.html ; ““Mythos Interpol” und sein Missbrauch durch autoritäre Regime” [“The Interpol Myth” and Its Abuse by Authoritarian Regimes,] Verfassungsblog, October 17, 2018, https://verfassungsblog.de/mythos-interpol-und-sein-missbrauch-durch-au….

- 51//www.dw.com/en/germany-halts-uighur-deportations-to-china/a-45190309 ; “Germany Halts Deportation of Chinese Muslims Over Human Rights Concerns,” The Local, August 24, 2018, https://www.thelocal.de/20180824/germany-halts-deportation-of-chinese-m….

- 52//ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/policies/migration-and-asylum/irregular-migration-and-return/return-and-readmission_en.

- 53//dserver.bundestag.de/btd/18/071/1807132.pdf.

- 54//www.justiceinfo.net/en/28797-german-arrest-of-top-aide-to-rwandan-ex-pr….

- 55//www.middleeasteye.net/news/germany-frees-detained-al-jazeera-journalist….

- 56//oc-media.org/chechen-asylum-seeker-extradited-from-germany-reported-killed/; Svetlana Gannushkina, “Why Are Residents of Russia Asking for Asylum in Europe?” Memorial Human Rights Center, 2019, https://refugee.ru/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Why-Are-Residents-of-Russ….

- 57//www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2422192/f01891c5efa5d6d89df7a5693eab5c9a/2….

The Long Arm of the Regime – Eritrea and Its Diaspora

Source: BPB

Nicole Hirt(Mehr zum Autor)öffnen

16.04.2020 / 8 Minuten zu lesen

- TeilenOptionen anzeigen

- Artikel drucken

- Inhalt merken

Interner Link:Auf Deutsch lesen

Many Eritreans have fled their country of origin. Yet, they cannot fully escape the radar of President Afewerki’s autocratic regime.

Zu den Inhalten springen

- The Emergence of Eritrea as a Transnational Political Space

- Independence and the Introduction of the Diaspora Tax

- Renewed War and Political Crisis

- Leaving Eritrea

- Splits in the Diaspora and the Foundation of the YPFDJ

- Sanctions and the Diaspora Tax

- The Long Arm of the Regime in Non-Democratic and Democratic Countries

- Eritrea at a Critical Juncture

The Emergence of Eritrea as a Transnational Political Space

Eritrea is the second-youngest country on the African continent and gained its de-facto independence from Ethiopia in 1991 after thirty years of armed struggle. An Italian colony from 1890 to 1941, Eritrea came under British administration in the course of World War II. In 1952, it was federated with Ethiopia and annexed by Emperor Haile Selassie in 1962. The independence war was initiated by the Muslim-dominated Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), but from the mid-1970s on, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) gained the upper hand. It lost previous support from conservative Arab countries and received no help from the Eastern Bloc because in Ethiopia a military council (Derg) had ousted Haile Selassie in 1974 and followed a socialist policy, which entailed the support of the Soviet Union.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[1] This left the EPLF with little backing, and it had to rely on the emerging refugee communities abroad. Due to Ethiopian war atrocities, hundreds of thousands of Eritreans fled their country Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[2] and settled in neighbouring countries and in Europe, the USA, Canada and Australia. The EPLF established mass organisations with oversea branches in order to organize and control the diaspora communities and to mobilise them for fundraising purposes in support of the armed struggle.

Independence and the Introduction of the Diaspora Tax

As soon as independence was achieved, the Provisional Government – composed of the EPLF leadership – introduced a rehabilitation or diaspora tax for all Eritreans living abroad.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[3] Since then, Eritreans outside the country have been levied two percent of their income, no matter if it comes from work or from social welfare benefits. In order to organize and control Eritrean communities abroad, the regime established a network of diplomatic missions in all countries with significant Eritrean diaspora presence. In addition, the government established the so-called mahbere-koms, purportedly apolitical cultural or community associations, which replaced the mass organisations in 1989.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[4] Eritreans obtain a “clearance” after having paid their dues, which is a precondition for obtaining passports, birth certificates, for the right to buy or to inherit property in the homeland and for many other services provided by Eritrean embassies and consulates.

Renewed War and Political Crisis

Initially, diaspora Eritreans were happy that independence had finally been achieved and looked forward to a bright future. Most of them volunteered to pay the tax, which they saw as a contribution to rebuild their war-torn homeland. The EPLF renamed itself People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) in 1994 and engaged in reconstruction and development. Yet, only five years after formal independence in 1993, renewed war broke out between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Although officially fought about the boundary line, personal rivalries between the leaderships of Ethiopia and Eritrea as well as economic issues have served as explanations.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[5] However, in retrospect the war can only be judged as a tragic policy misstep that took the lives of up to a hundred thousand people.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[6] The war triggered a political debate, and a reform group within the ruling party, the so-called G15 demanded reforms and democratic elections. Yet, President Isaias Afewerki put the reformers behind bars in September 2001. Since then, Eritrea has turned into an autocracy without implemented constitution and rule of law Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[7], with no civil liberties and an open-ended national service Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[8] with the aim of passing the wartime-values of the EPLF to the next generation. The national service has been the main reason for a massive population exodus of hundreds of thousands of Eritreans although the regime tried to contain it by shoot-to-kill orders at the border.

Leaving Eritrea

In recent years, up to 5,000 Eritreans have crossed the borders to Ethiopia and the Sudan every month Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[9], but large numbers did not register as refugees and tried to continue their journey to Europe. According to the European Asylum Support Office, there were 47,020 total asylum applications of Eritreans to EU countries in 2015 and 38,808 in 2016.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[10] Currently, 175,000 Eritreans live as refugees in Ethiopia.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[11] Sudan hosts more than 100,000 registered refugees Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[12], but large numbers of Eritreans live unregistered in the large cities or have a dual nationality.

Splits in the Diaspora and the Foundation of the YPFDJ

These events had their repercussions in the diaspora: new opposition parties and civil movements emerged, and the diaspora tax became controversial. In order to enhance control over the diaspora youth, the regime founded the Young PFDJ (YPFDJ) as its youth branch abroad with the aim of indoctrinating young Eritreans and raising funds through festivals and donations. The government regards all Eritreans including diaspora-born youth as Eritrean nationals even if they have acquired citizenship of another country, and the government uses feelings of obligation and pressure to extract money from them.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[13] On the other hand, government opponents began to lobby against the tax due to the regime’s opacity and lack of accountability.

Sanctions and the Diaspora Tax

The UN Security Council imposed sanctions on Eritrea in 2009 for its alleged support to armed groups in the Horn of Africa, including the Islamist Al-Shabaab militia in Somalia and tightened them in 2011. The government was now obliged to stop using coercive measures to levy the diaspora tax. This triggered some reactions from democratic states such as Canada and the Netherlands, who declared Eritrean diplomats involved in tax collection Personae non Gratae. Eritrean diaspora communities remained divided, but the government used the sanctions to create a rally-around-the-flag effect and called for a “resolute national rebuff”. It organised demonstrations, but most importantly used the sanctions to raise even more funds from diaspora communities worldwide to counter alleged foreign conspiracies.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[14] Little is known about the raised amounts and their whereabouts because the government does not publish such information, but according to estimates, around one third of the Eritrean budget is derived from the diaspora tax alone.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[15] The sanctions were terminated in November 2018 after Eritrea’s rapprochement with Ethiopia on the initiative of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

The Long Arm of the Regime in Non-Democratic and Democratic Countries

The long arm of the Eritrean regime is felt strongly in non-democratic countries, where Eritreans are regarded as labour migrants and not as political refugees. For instance, hundreds of thousands of Eritreans live and work in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. They need valid passports in order to get work permits and are forced to pay the diaspora tax because they depend on the services of the Eritrean diplomatic missions. They are also supposed to attend government seminars Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[16] and to donate money.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[17] In Eastern Sudan, many Eritreans feel unsafe because local officials use to cooperate with agents of the Eritrean regime and some opposition activists have been deported Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[18].

However, Eritrean transnational institutions are also playing an important role in democratic countries, including Germany. Embassies and consulates, community organizations (mahbere-koms) and the YPFDJ have all played a role in raising funds from the diaspora over time. Those who fled repression and the timely unlimited national service and have been granted refugee protection in recent years are also targeted by agents of the regime. For example, government supporters have visited refugee shelters to encourage refugees to pay the diaspora tax Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[19], and government-friendly interpreters have tried to manipulate personal interviews in asylum procedures at the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[20] Recent field research by the author revealed that the government has infiltrated parts of the the clergy of Eritrean Orthodox Church communities throughout Europe and that fees for religious services like baptisms and marriages are being transferred to Eritrea.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[21] In addition, refugees who approach the Eritrean diplomatic missions to obtain services need to sign a “letter of regret” in which they confess themselves guilty of having failed to fulfil their national obligations and agree to accept any punishment the regime might deem appropriate – and they agree to henceforth pay the diaspora tax.

Eritrea at a Critical Juncture

Close to thirty years after independence, Eritrea has become a diasporic state with up to half of its population living shattered across the world.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[22] The PFDJ regime, which has ruled the country without holding national elections and has perpetrated gross human rights violations, relies on transnational political structures that serve to control, streamline and intimidate the diaspora. Many second-generation diaspora Eritreans have internalized the government’s narrative of a heroic nation beleaguered by enemies, while others organize themselves in pro-reform movements and refuse to get in touch with Eritrean transnational institutions. After the 2018 peace agreement with Ethiopia, Eritrea is at a crossroads: while the government has yet to introduce reforms and to release political prisoners, increasing numbers of Eritreans are saying “Enough!” (or “Yiakl“!) through a vibrant international social media campaign.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[23] These pro-democratic forces will be needed to democratize the country and to put an end to the timely unlimited national service, which amounts to forced labour and has triggered an immense exodus that threatens to destroy the social fabric of the country.Zur Auflösung der Fußnote[24]

Quellen / Literaturzuklappen

Hirt, Nicole/Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad (2013): ‘Dreams Don’t Come True in Eritrea’: Anomie and Family Disintegration Due to the Structural Militarization of Society. Journal of Modern African Studies 51 (1), pp. 139-168.

Hirt, Nicole (2014): The Eritrean Diaspora and Its Impact on Regime Stability: Responses to UN Sanctions. African Affairs 114 (454), pp. 115-135.

Hirt, Nicole/Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad (2018a): By Way of Patriotism, Coercion or Instrumentalization: How the Eritrean Regime Makes Use of the Diaspora to Stabilize Its Rule. Globalizations 15 (2), pp. 232-247.

Hirt, Nicole/Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad (2018b): The Lack of Political Space of the Eritrean Diaspora in the Arab Gulf and Sudan: Torn between an Autocratic Home and Authoritarian Hosts. Mashriq & Mahjar 5(1), pp. 101-126.

Hirt, Nicole (2001): Eritrea zwischen Krieg und Frieden. Die Entwicklung seit der Unabhängigkeit. Institut für Afrika-Kunde. Hamburg.

Kibreab, Gaim (2018): The Eritrean National Service. Servitude for the ‘Common Good’ and the Youth Exodus. Woodbridge: James Currey.

Koser, Khalid (2003): Mobilizing New African Diasporas: An Eritrean Case study. In: Khalid Koser (ed.): New African Diasporas. London: Routledge, pp. 111-123.

Mengis, Eden (2015): “Sprich nicht so über dein Land!”: Tigrinya-Dolmetscher in Anhörungen vor dem Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. Masterarbeit, Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität Mainz.

Negash, Tekeste/Kjetil Tronvoll (2000): Brothers at War. Making Sense of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War. Woodbridge: James Currey.

Ogbazghi, Petros (2011). Personal Rule in Africa, the Case of Eritrea. African Studies Quarterly 12(2), pp. 1-25.

Pool, David (2001): From Guerillas to Government: the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front. Oxford: James Currey.

Styan, David (2007): Discussion Paper: The Evolution, Uses and Abuses of Remittances in the Eritrean Economy. Conference Proceedings, Eritrea’s Economic Survival, London, Chatham House, pp. 13-22.

Trivelli, Richard M. (1998): Divided Histories, Opportunistic Alliances: Background-Notes on the Eritrean-Ethiopian War. In: Afrika Spectrum 33 (3), pp. 257-289.

World Bank (1994): Report No. 12930-ER: Eritrea. Options and Strategies for Growth (in two volumes). Washington D.C.

Young, John (1996): The Tigray and Eritrean People’s Liberation Fronts: A History of Tensions and Pragmatism. In: The Journal of Modern African Studies 34, pp. 79-104.