South African history suggests that a tie-up between the ANC and the DA is perhaps not such a strange beast after all

27 JUNE 2024 – 05:00, by MATTHEW BLACKMAN

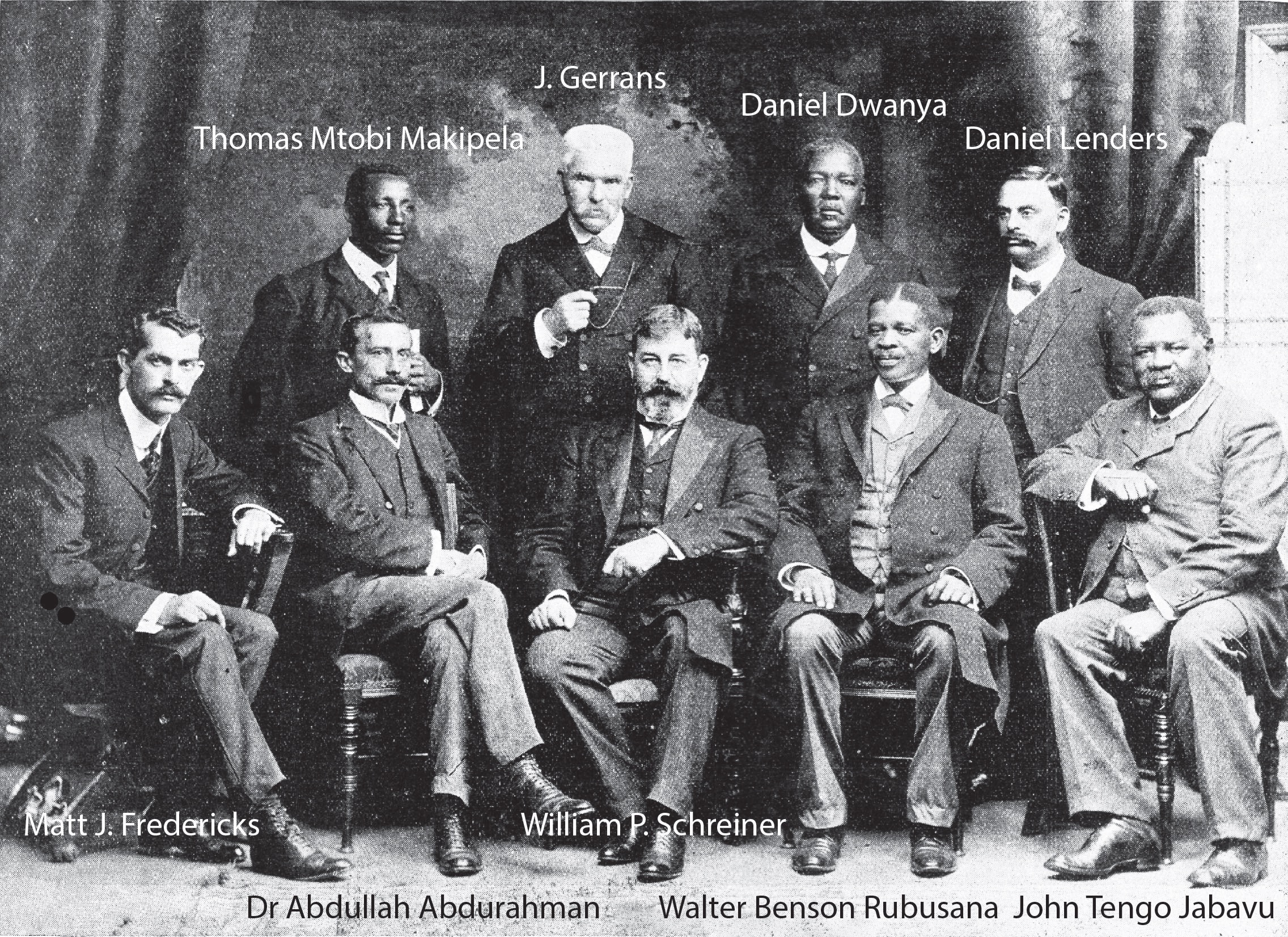

The 1909 Delegation that went to Britain to demand a non-racial vote for South Africa when the Union was founded in 1910.

Three weeks ago, the very idea of an ANC and DA coalition may have seemed as unlikely as the Israel/Palestine two-state solution. But as Tony Leon regularly reminds us, the ANC, under Nelson Mandela, courted the then Democratic Party to join his government of national unity (GNU) after the National Party withdrew from it in 1996. Still, the ANC has a far longer history of collaboration with what many term “white liberals”.

The ANC has its origins in the Eastern Cape, with the formation of the South African Native Congress in about 1890. Its first leaders, Nathaniel Mhala, Walter Rubusana and AK Soga, were all mission-educated men; Mhala and Soga were educated in the UK. And it should be noted that all three men had the vote in the Cape colony. As such, in 1898, they took the dramatic decision to support Cecil John Rhodes’s Progressive Party against the Afrikaner Bond. In fact, Rhodes helped finance their newspaper, Izwi Labantu.

The reasons for this seeming unholy alliance with the British and Rhodes are complicated. However, they can be summed up by one of the early ANC’s own, the half-Irish, half-Herero Robert Grendon, in his epic poem Paul Kruger’s Dream: “Great Britannia — thou — that givest / Equity to ev’ry man.”

Then there’s Selby Msimang, another founder of the ANC, who went on to help found the Liberal Party (LP) in the 1950s with Margaret Ballinger, Alan Paton, Leo Marquard and Manilal Gandhi (Mahatma Gandhi’s son, who was also a member of the ANC). Msimang saw no problem with dual membership. As the LP developed under the leadership of Paton, it established ties with the ANC under Albert Luthuli.

The LP was invited by none other than the ANC’s Walter Sisulu to participate in the famous 1955 Congress of the People (COP) at Kliptown, where the Freedom Charter was drafted. Msimang was a strong advocate for the LP’s participation in the planned COP. However, due to the participation of the white communists, the LP decided to boycott the gathering. As Paton wrote later, the LP’s decision not to attend resulted in Luthuli “being pushed further into the arms of the Left”.

Randolph Vigne, then a young member of the LP, believed this to be his party’s biggest political mistake, as it damaged the ANC/Liberal collaboration. It also resulted in the communists having almost exclusive control over the editing of the Freedom Charter. As Vigne pointed out, the Liberals agreed with everything in the charter, except for the nationalisation of the “mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks, and the monopoly industry”.

Vigne himself would go on to collaborate with members of the ANC. In 1963, he was instrumental in establishing the sabotage group the African Resistance Movement (ARM). Considered by some to be the LP’s “military wing” (though never condoned or acknowledged by any of its main leaders except Vigne), the ARM in fact had several ex-members of the ANC within its pitifully small ranks.

During this period, many liberals, along with communists and members of the ANC, were imprisoned and banned. And many collaborated with each other in apartheid-era jails. However, liberals such as Roman Eisenstein, Hugh Lewin and Peter Brown never fully integrated into the ANC, largely because of its ties with USSR-supporting communists. (Ironically, one of the hurdles the collaboration between the DA and ANC will negotiate is that of the ANC’s association with Russia.) But the liberals’ local anti-apartheid politics was almost indistinguishable from that of many within the ANC.

Eddie Daniels, the only member of the LP to serve time on Robben Island, did, in fact, ultimately join the ANC, as did many Left-leaning liberals (or social democrats) such as Alec Erwin and Derek Hanekom, who both, as members of the ANC, were part of South Africa’s first GNU.

As Mandela often suggested, the ANC was always a “broad church” that allowed many competing ideologies within its ranks. The history of the ANC has always been one of inclusion. Its initial premise in 1912 was based on the attempt to include all black ethnic groups in South Africa. In 1947, it drafted the “Three Doctors’ Pact”, signed by doctors Alfred Xuma, Yusuf Dadoo and Monty Naicker, bringing in Indians under the ANC’s umbrella. Its collaboration with white communists and white liberals in the 1950s was another significant development in its history.

Selby Msimang, another founder of the ANC, went on to help found the Liberal Party in the 1950s with Margaret Balinger, Alan Paton, Leo Marquard and Manilal Gandhi

Many, however, believe that the ANC’s latest attempt at inclusion with Ramaphosa’s GNU is a bridge too far across the Rubicon. That is, on a policy level, the DA and ANC are too divergent. But it was not that long ago that the DA of Mmusi Maimane, who won only three fewer seats in 2019 than John Steenhuisen’s did in 2024, was criticised for being “ANC-lite”. In fact, the DA’s greatest electoral success to date was under Maimane in the 2016 local government election. This was an election where the DA led with the message that it would “restore the values of Mandela’s ANC”.

The reality is that the DA’s shift to the right has borne little fruit. In the 2021 local election, the party lost significant support, while in the national election, it still has two fewer seats than it did under Helen Zille’s more liberal DA in 2014.

This seems to confirm that the DA can almost certainly move a little towards the ANC on a policy level without damaging its brand irreparably. However, having now pinned to the mast a plethora of anti-ANC policies and rhetoric, its volte-face will have to be managed with subtlety.

In fact, it is the ANC, even with its long history of collaboration with white liberals, that might damage its voter appeal with the GNU. But if there is a man who can negotiate with and befriend his political opponents, it is Ramaphosa — as he showed when he helped negotiate South Africa’s first GNU in the early 1990s. Just whether he has it in him, after 30 years of grinding and, at times, ruinous politics, is yet to be seen. But the history of the ANC suggests that this form of collaboration is in many ways in its DNA.

As Grendon argued, the British had freed the slaves in the Cape Colony in 1834 and given black men the vote in 1854.

Grendon and Rubusana would end up regretting their support for Rhodes and his Progressive Party, who proved to be false friends. (There is no small irony that Rhodes considered himself “progressive” much in the mould of Julius Malema and Jacob Zuma today.) However, when the Union of South Africa was proposed in 1908, Rubusana continued his alliance with true white liberals.

Rubusana joined the Cape’s liberal ex-prime minister, WP Schreiner, on his 1909 delegation to the UK. The delegation went to its colonial master to protest against the various racial clauses of the proposed South Africa Act — the act that would unite South Africa into one country. The delegation was one of the first acts of multiracial national unity, containing white, coloured and black members.

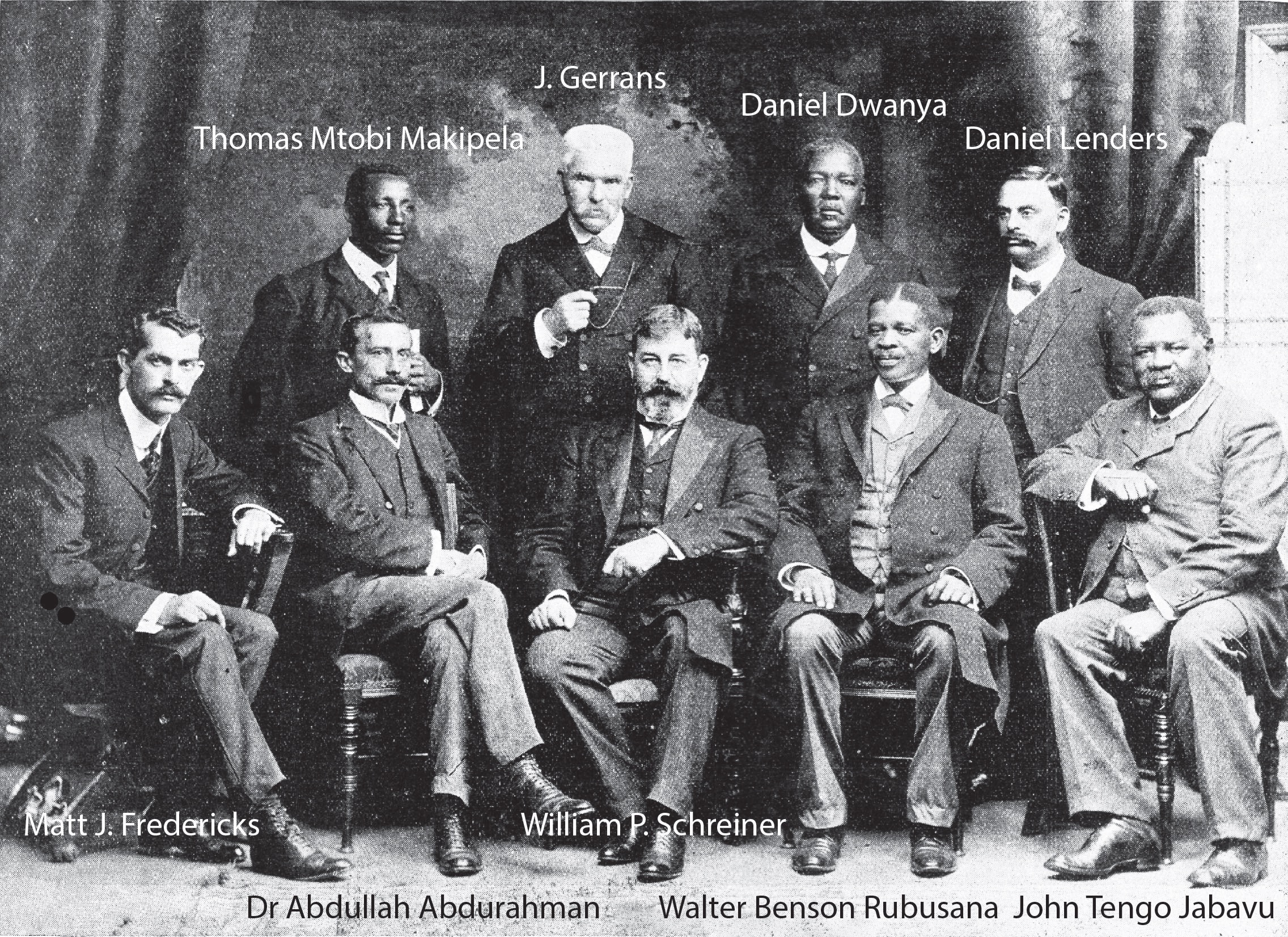

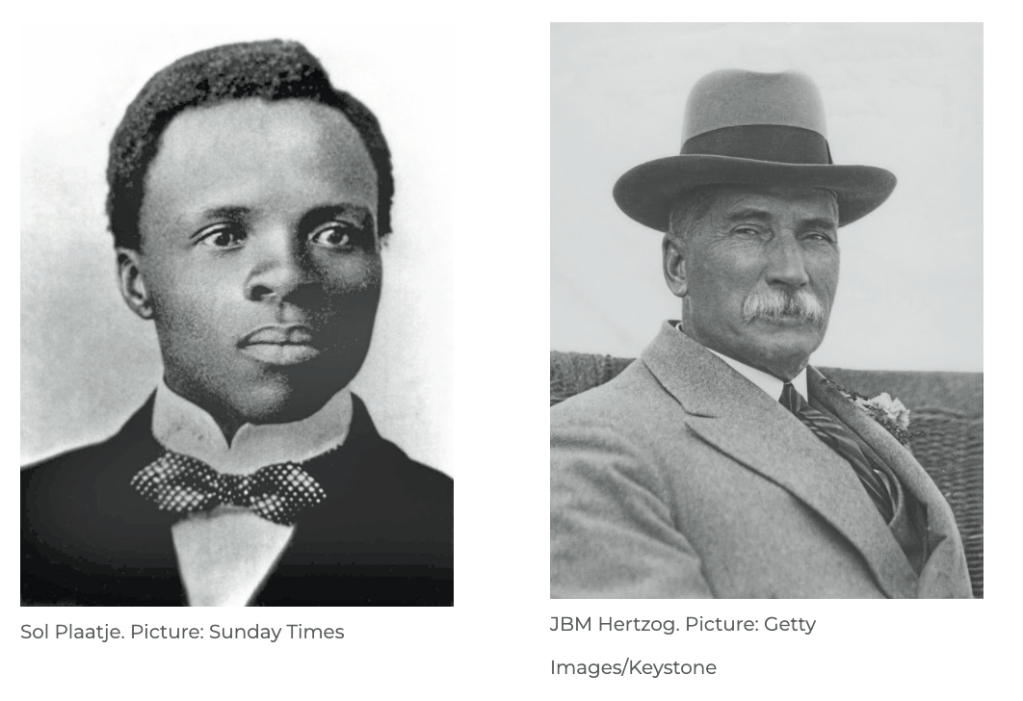

Another ANC stalwart and founder, Sol Plaatje, spent much of his life surrounded by white liberals. In the 1898 election in the Cape, he voted against Rhodes for very particular liberal reasons. Plaatje voted for Henry Burton. As he wrote: “I sympathised with advocate Burton during the last election … because he was a negrophilist and did a lot for us while I was in Kimberley.” Burton would go on to become South Africa’s first (liberal) minister of native affairs in what was, in many ways, prime minister Louis Botha’s attempt at a GNU in 1910. The government contained the liberal Burton, liberal centrists such as FS Malan, as well as the racist JBM Hertzog.

However, Burton slowly lost faith in Botha and Jan Smuts (and their false pandering to liberalism) and went on to help found the Non-Racial Franchise Association. Plaatje begged Burton to return to politics in the 1920s, stating that black men, who still had the vote in the Cape after the Union of South Africa, would be “as keen as mustard” to vote for him.

But Plaatje’s association with white liberals went further than that. When the South African Native National Congress (later simply the ANC) sent a delegation to the UK in 1914 to protest against the Natives Land Act, Plaatje was drawn into suffragette circles. These included Betty Molteno, Sylvia Colenso and Georgiana Solomon. The women were members of three of the most famous liberal families in South Africa. Solomon and Molteno became close confidantes of Plaatje. In 1923, Colenso collaborated with Plaatje on the piano in the first recording of what was already, by then, the anthem of the ANC, Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, for Zonophone Records.