Continent finds itself wooed by many, but few countries have yet devised a strategy to take full advantage

Source: Financial Times

David Pilling(opens a new window) in London

Many of Africa’s leaders will descend on Beijing next month for the latest three-yearly summit with China. For leaders from the continent, these collective jamborees have become a familiar part of global summitry — and not just with China.

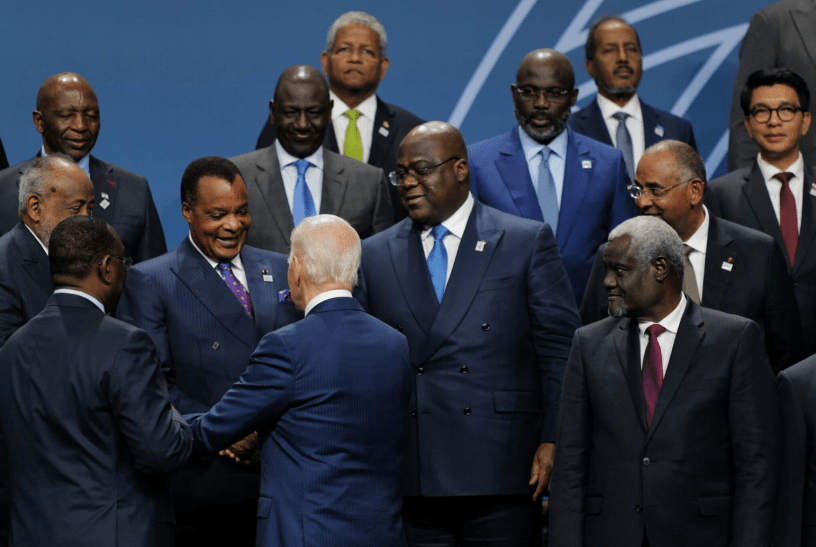

In the past two years alone, the 54 African heads of state have been invited en masse to Washington for a US-Africa summit hosted by President Joe Biden, to St Petersburg for the second Russia-Africa summit with President Vladimir Putin, and to March’s Italy-Africa summit in Rome presided over by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

African leaders have also had their choice of invitations to similar gatherings in Turkey, Saudi Arabia and, just this June, South Korea — the latest country to get in on the act of African summitry. Many will also fly off to Yokohama next year as Japan becomes the latest host.

Lazarus Chakwera, Malawi’s president, reflecting recently on the bonanza of diplomatic, security and trade opportunities open to African nations, told his hosts during a visit to London that, while it was “good to have a Chinese meal sometimes”, an all-you-can eat buffet was even better.

China is certainly not the only option on the menu. Measured by dispersed loans, Chinese interest in Africa peaked in 2016 when sovereign lending was worth $28.4bn, according to figures compiled by Boston University, versus lending of about $1bn in 2022.

Clamour for Africa

This is the second in a series examining the changing roles of foreign nations in African politics, security and trade

Part 1: The US-backed railway sparking a battle for African copper – see below

Part 2: The foreign powers competing to win influence in Africa – today

Part 3: Turkey’s expanding role in Africa (coming Tuesday)

But as attention from China has cooled, interest from several other nations, including Russia, India, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey and Brazil, has increased.

Africa is usually not at the top of the world’s diplomatic agenda, particularly at a time of conflict in the Middle East and Europe. But experts say many countries feel the need to develop or renew their “Africa strategy” because of the continent’s rapidly growing population, its high concentration of critical minerals and its 54 votes at the UN.

Chidi Odinkalu, a professor at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, said he was worried that rather than benefiting from having a seat at so many tables, Africa continues to find itself on the menu. He also wonders what it said about the continent that single countries deemed it acceptable to negotiate with all the collective leaders of Africa at once.

In theory, what Odinkalu calls the new “diplomatic polycentricity” presents opportunities. “The question is: is Africa configured in any way to take advantage? The fact that the African side has not gone past primary production shows that very clearly is not,” he said.

According to figures from the World Bank, despite all the interest from potential investors, manufacturing has declined as a percentage of gross domestic product in sub-Saharan Africa, falling from 18 per cent in 1981 to 11 per cent last year.

Most African countries remain locked in colonial-style trading relationships in which they export raw materials and import finished goods, Odinkalu said. “I think it’s a story of missed opportunities.”

While African countries may not have deepened their trading and investment relations, they have certainly broadened them.

India has become the third-biggest trading partner with the continent after the EU and China. Meanwhile, the UAE’s trade with Africa has increased nearly fivefold in the past 20 years — much of it gold and diamonds — to make the nation the continent’s fourth-biggest investor, with cumulated investments of nearly $60bn in the past decade.

One of the risks of having so many options, said Kenyan political commentator Patrick Gathara, was that some African governments, including his own, have borrowed too much. Zambia, Ghana and Ethiopia have all defaulted and the IMF estimates that 25 African countries are at high risk of debt distress. Kenya’s efforts to meet its loan obligations by squeezing more tax from its people brought waves of mass protests on to the streets, forcing President William Ruto to backtrack.

Alex Vines, head of the Africa Programme at Chatham House, a UK think-tank, said African nations were trying to “better define” their national interests. Like Odinkalu, he worries that they do not always have the diplomatic or civil service bandwidth to take advantage.

Vines compared the strategy of being friends with many nations but the client of none with the stance taken by Djibouti, which has rented out its Red Sea coastline for the bases of several competing powers, including China, the US, France and Japan.

South Africa — a member of the Brics nations alongside Brazil, Russia, India and China, and now Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the UAE — has pursued a sometimes uncomfortable non-aligned policy that has seen it conduct naval operations with Russia and China while courting investments from the west.

Ken Opalo, an associate professor at Washington’s Georgetown University, said too much interest in the continent by outside players was not always a good thing.

He cited as an example the war in Sudan, which erupted last year and dragged in “middle powers”, including the Gulf states and neighbours such as Egypt and Ethiopia. The UAE, in particular, is accused of stoking the conflict by backing the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces.

Opalo fears the war will result in “a Libyan stalemate”, a reference to another messy ending to a conflict that several foreign powers became embroiled in.

In Europe, despite the trade opportunities, Africa is often regarded as a potential source of instability, terror and migrants due to its population being forecast to reach 2.5bn by 2050, Isis and al-Qaeda affiliated insurgencies, and political uprisings.

Mali and Niger cut diplomatic ties with Ukraine this month amid an escalating dispute over whether Kyiv provided support to rebels that killed Malian soldiers and mercenaries linked to Russia’s private military group Wagner.

Coups in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have been followed by the juntas expelling French and US troops and forging closer ties with Russia and Wagner. In most cases, the shift has been accompanied by an increase in violence, according to Acled, an organisation that collects conflict data.

“A lot of African countries are trying to find a middle way through all of this,” said Vines. “And there lies the difficulty. There’s a lot of miscalculation.”

Part 1 The US-backed railway sparking a battle for African copper

Washington’s support for a minerals train connecting the DRC to the Atlantic illustrates its desire to compete with China

by Andres Schipani(opens a new window) in Lobito

As the US ambassador’s car pulled into a port terminal on Angola’s Atlantic coast last month, the longshoremen queueing for work were ecstatic at the sight of the stars and stripes. “Nós amamos os Americanos!” they shouted in Portuguese, the country’s official language. “We love Americans!”

This newfound passion for Washington is surprising in a country that was once a cold war battleground, an ally of Moscow and later the largest recipient of Beijing’s loans in Africa. But it is not unwarranted. The US is helping to finance the Lobito Corridor, a revival of a 100-year-old railway line that will transport critical minerals across the wider region. It connects the resource-rich Democratic Republic of Congo, in central Africa, to Angola’s port of Lobito, to the west.

The overall project is ambitious and will cost at least $10bn, according to estimates from Angolan officials. As well as the railway, it comprises roads, bridges, telecommunications, energy, agribusiness and a planned extension to Zambia’s lucrative Copperbelt province.

US involvement in Lobito is no isolated act, but part of a strategy to reverse its diminished influence in Africa, where others such as China, Russia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates have gained ground.

China has a particularly large footprint in Africa, thanks to its $1tn Belt and Road Initiative. Beijing’s offer to finance and build infrastructure in mostly poorer countries gives it an advantage in the race for control of minerals that are critical for defence, renewable power and electric vehicles.

The Lobito project will not only be beneficial for Angola, supporters say, but it will also help to bridge an infrastructure gap of up to $170bn a year on the continent, according to estimates from the African Development Bank, another of Lobito’s financing partners, alongside Italy.

“This is a project that will showcase the American model of development,” says US ambassador Tulinabo Mushingi. “We need to have allies that agree with our way of doing business.”

The core goal of the Lobito Corridor is to create the quickest, most efficient route for exporting critical minerals from the central African copper belt and on to the US and Europe. Two years ago, a consortium of European companies — Swiss trader Trafigura, the Portuguese construction group Mota-Engil and the Belgian railway specialist Vecturis — won a 30-year concession for the Lobito Atlantic Railway (LAR) to manage the transport of minerals across 1,300km of rail tracks inside Angola. It is also upgrading and operating the mineral port.

“This is an easy entrance for US soft power,” says Gracelin Baskaran, director of the critical minerals security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think-tank.

China controls much of the global extraction and refining of critical minerals, so the line can still be used by Chinese miners, but “the cargo that leaves this corridor does not go exclusively to China,” says Angola’s transport minister, Ricardo Viegas D’Abreu. “Everyone needs minerals.”

But Angola has to tread carefully due to the fragility of its oil-dependent economy and its huge debt burden to Beijing. Of the $45bn Luanda has borrowed so far, it still owes about $17bn — just over a third of its total debt — to China mostly in the form of loans backed by oil.

“Angola is doing the smart thing many African countries are now doing: they want to be friends with everyone but they don’t want to be owned by anyone,” says Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, an Oxford university professor of African politics.

“President João Lourenço does not want Angola to be trapped in a new cold war.”

Angola has been moving on from decades of conflict. After a drawn-out civil war that ended in 2002, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) — the party that has dominated politics in the country since independence from Portugal in 1975 — oversaw an oil and construction boom, much of it underwritten by Chinese loans.

But in recent years, Lourenço has been courting the US and Europe, seeking to drum up foreign investment and persuade western capitals that Angola is no longer as closely allied with Russia or China as it had been under his late predecessor, José Eduardo dos Santos.

“We meet at a historic moment,” President Joe Biden said when he welcomed Lourenço in Washington last year, hailing Lobito as the “biggest US rail investment in Africa ever”. “America is all in on Africa,” he added. “And we’re all in with you and Angola.”

Lourenço was equally effusive, thanking Biden for changing “the co-operation paradigm” between the US and Africa.

Through the G7, the US is offering the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) to developing nations as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative and aims to deploy more than $600bn by 2027. The US International Development Finance Corporation has approved a loan of $250mn to support the renovation of the Angolan railway line, as well as other investments.

“Lobito is the flagship [project], the test case for other economic corridors we are working on. Now we can continue to accelerate the growth and prosperity of that corridor and use it as a model to replicate in other parts of Africa and the world,” says Helaina Matza, the acting special co-ordinator for the PGII, which is backing the development of an economic corridor in the Philippines.

Behind the wheel of a General Electric locomotive, painted in Angola’s colours of red, black and yellow, driver Paulo Mucanda agrees that Lobito “is a very good thing for Angola and for Africa”.

Since trial shipments started in January, Mucanda has been ferrying copper to the port from the Angola-DRC border town of Luau, where the rail line meets the 400km network operated by the Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer du Congo (SNCC) coming from Kolwezi. The area is home to one of the world’s largest copper mines and Lobito’s anchor customer, Kamoa-Kakula, a joint venture between Toronto-listed Ivanhoe, China’s Zijin and DRC’s government.

Mucanda’s journey to the Atlantic coast takes roughly a week — a quarter of the time it typically takes to transport goods by road to ports much further away on the Indian Ocean.

Ivanhoe said that last year about 90 per cent of Kamoa-Kakula’s concentrates were shipped from Durban in South Africa and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, where the average round-trip takes up to 50 days. The rest went to Beira, in Mozambique, and Walvis Bay in Namibia, also a longer route than the journey to Lobito.

And not only is transportation by rail quicker, it is also cheaper and better for the environment than trucking. “Cheaper logistics increase the amount of economically recoverable copper,” says Robert Friedland, the billionaire founder of Ivanhoe.

The Lobito Atlantic Railway forecasts it will initially carry 200,000 tonnes of minerals this year, aiming to reach 2mn in the future. “Now there is a choice between going to the Atlantic Ocean or the Indian Ocean. It is not about things going to China or going to the United States. Here, you are balancing the forces,” says Francisco Franca, LAR’s chief executive.

Franca explains that the brownfield project includes an investment of more than $860mn over the lifetime of the concession — mostly in Angola and some of it in the DRC — as well as securing more than 1,500 wagons and 35 locomotives.

There is also potential for greenfield investment if, as planned, the line extends by 800km into Zambia, where international companies have invested billions in mining projects. This includes KoBold Metals, a California-based mineral exploration company underpinned by venture capitalists backed by Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

“Anyone who’s in the renewable space in the western world . . . is looking for copper and cobalt, which are fundamental to making electric vehicles,” says Mfikeyi Makayi, chief executive of KoBold in Zambia. “That is going to come from this part of the world and the shortest route to take them out is Lobito.”

Lobito is building on the existing infrastructure of the Benguela Railway Company, a concession granted in 1902 to Sir Robert Williams, a Scottish entrepreneur.

Before Angola gained independence, the company carried more than 3mn tonnes of freight and had first-class passenger coaches decorated with brass, leather and mahogany. During the civil war, the railway was often sabotaged by the then Washington-backed National Union for the Total Independence of Angola fighting the MPLA, which was supported by Moscow and Havana.

By the end of the 27-year war, only 34km of operating rail remained. In 2005, Angola accepted $1.5bn in Chinese finance to upgrade the railway and the port of Lobito. The work was completed by the China Railway 20th Bureau Group Corporation around 10 years ago mainly using Chinese labour — a typical feature of Beijing’s infrastructure projects in Africa at that time.

What Angola failed to achieve over the years until now was to find an economic and financial model for the viability and activation of the corridor

Yet it was barely used. “What Angola failed to achieve over the years until now was to find an economic and financial model for the viability and activation of the corridor. We needed someone who could offer finance, someone who could invest and someone who can put cargo in the corridor,” says Viegas D’Abreu, the transport minister.

This is where Washington came in. Supporters of the Lobito Corridor — which includes more than $1.2bn in US financing for construction of solar energy power plants and bridges around rural communities — argue that unlike Beijing’s approach, Washington’s model is tied to local development.

China’s initiative to finance and build infrastructure around the world has attracted a chorus of criticism over the past decade. Many projects have been mothballed, linked to corruption and others have resulted in some countries building up unsustainable debts. Kenya’s $5bn standard gauge railway, for example, has been criticised for not being economically viable or benefiting local communities.

“There’s no denying this is a response to the Belt and Road. The difference being it’s an integrated approach, not just building infrastructure to ship raw material out,” says Peter Pham, a former US special envoy to the Sahel and Great Lakes region of Africa in the Trump administration.

But Beijing has also been rethinking its strategy. At the third Belt and Road forum last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s keynote speech concentrated on sustainable, community-focused projects, something he is expected to underline at next month’s Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in Beijing.

“Previous versions of this kind of project have focused narrowly on extraction and enrichment,” says Ziad Dalloul, president of US-owned telecoms provider Africell, which is building digital infrastructure in Angola. “They offered huge rewards to those who ended up in possession of resources, but created virtually no benefits to adjacent communities. The Lobito Corridor is different — more than just a railway line.”

David Maciel, chief executive of Carrinho Agri, Angola’s top agribusiness conglomerate that is building plants and silos along the railway, agrees that Lobito is “much more than a minerals train”. Carrinho Agri says it will also boost the number of farmers it works with along the rail line from 60,000 today to 1.4mn by 2030, spurring agricultural output and food security in Africa.

This is important for Angola, whose economy is not generating enough jobs. João Sapalo Chifanda, who queued to get a job as a stevedore at the Lobito port, is hoping the corridor will “finally bring development to poor Angolans” who make up about 36 per cent of the total 38mn population.

The project “will bring socio-economic benefits to Africa while benefiting western minerals security needs,” says Baskaran at CSIS. “The US is offering Angola an alternative to Chinese predatory lending.”

Washington faces a steeper challenge across the border. The Congo mining sector remains dominated by Chinese companies, helping to fuel the nation’s rise as a powerhouse in providing raw materials for the clean technology.

In January, China pledged up to $7bn in infrastructure investment in a revision of the Sicomines copper and cobalt joint venture agreement with Kinshasa. Data from the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think-tank, shows investments linked to the Belt and Road Initiative in Africa topped $10.8bn last year, the highest level of Chinese activity in mining, energy and transport in the continent since 2005.

In February, Beijing offered more than $1bn to modernise the Tazara railway line — originally funded by Mao Zedong’s government in the 1970s — that links the port of Dar es Salaam to Zambia’s Copperbelt province.

“The reality of the Lobito Corridor is that it may be coming too late in the day. This is certainly true as far as transporting critical raw minerals to the US and EU, since most of the supply has already been locked in by China,” says ED Wala Chabala, a former board chair of Zambia Railways Limited.

Other obstacles remain. The first is regional: Although DRC President Félix Tshisekedi said that Africa must “integrate in order to progress and prosper together” as he signed the Lobito Corridor agreement last year, senior Angolan officials grumble that Congo’s engagement has been “timid”.

But Luanda needs the co-operation of Kinshasa to streamline customs and allow for the much shorter Congolese section of the corridor run by the local operator to be renovated. DRC officials declined to comment.

“The efficiency alignment between the countries has to take place,” says a senior foreign miner operating in Congo. “We’ve gone through ebbs and flows.”

Then there are barriers at home. Fernando Pacheco, a land expert and former senior member of the MPLA, says the Angolan state may “not have the capacity” to oversee the Lobito Corridor and fears it could turn into another “white elephant” like the Chinese-upgraded Benguela railway.

The final hurdle is a matter of politics. “A long-term project like the Lobito Corridor is vulnerable to political changes in these three African countries and in the United States,” says Baskaran. “A change in administration could usher in a downsizing or elimination of the project.”

A Kamala Harris government in the US would be likely to continue with Lobito-type investments, possibly including the Liberty Development Corridor connecting southern Guinea to Liberia’s coast. A Trump administration, however, may ask “to what extent is this a meaningful countermeasure for the Chinese?” says Frank Fannon, former US assistant secretary of state for energy resources under Trump.

For now, though, after years of declining influence in Africa, the US is revelling in its growing love-in with Angola. When the railway-port concession was transferred to the LAR in 2023 — having beaten a Chinese consortium a year earlier — US ambassador Mushingi sent his bosses a copy of a local newspaper with a headline that read: “Americans ‘dislodge’ the Chinese”. Washington was said to be thrilled.