Rwandan support for the M23 may have strained numerous diplomatic relations, but the growing security gap in Africa and threat of Russian influence will likely continue to make the RDF a preferred alternative for multilateral and bilateral military cooperation in the region.

The Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) operations abroad signal a shift in Rwanda’s regional standing

Posted: 27 September 2024| Region: Africa | Category: Analysis

Authors: Ladd Serwat; Peter Bofin

Source: Acled

Register for a live webinar on Tuesday 15 October 2024 examining Rwanda’s security interventions.

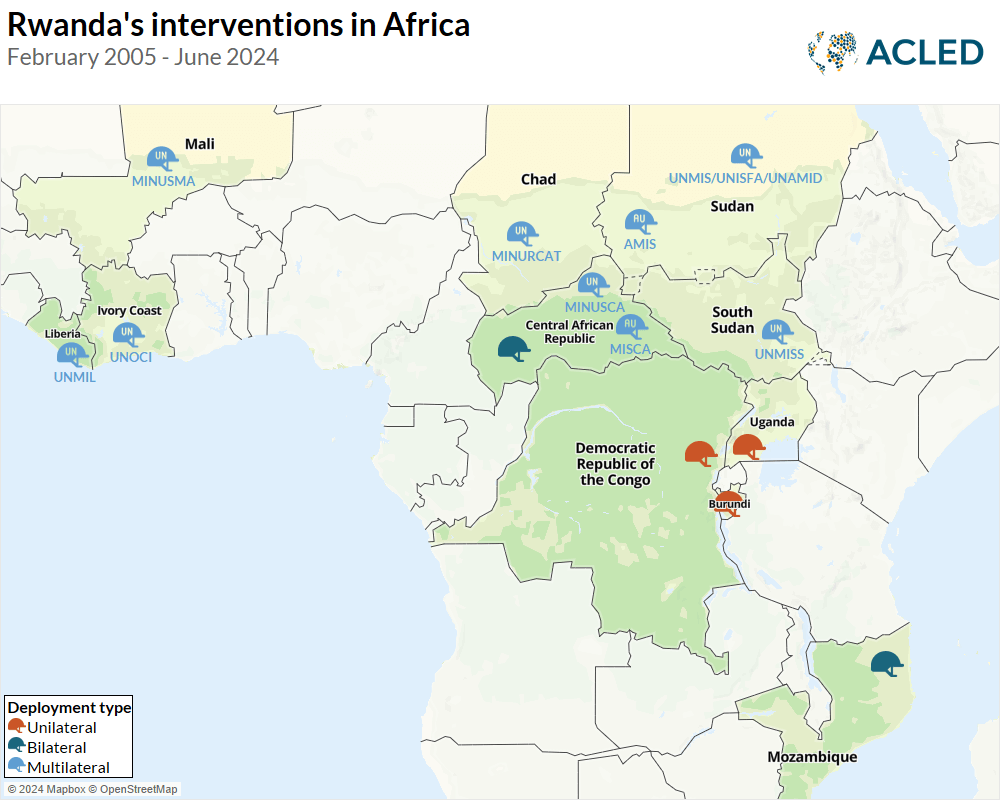

Amidst mounting criticism against the failures of United Nations peacekeeping and Western military involvement, an increasing number of African governments across the continent have demanded the withdrawal of former military partners.1 These emerging security gaps have been increasingly filled by new armed actors and forms of cooperation, including private military companies, local self-defense groups, and regional partnerships. Having long contributed to multilateral peacekeeping missions, Rwanda has positioned itself as an alternative security partner, sending bilateral missions across the continent.2 The Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) began engaging in further bilateral operations in late 2020 when RDF soldiers and special forces deployed to the Central African Republic to counter a rebel offensive. That engagement expanded in 2021 when Rwanda deployed forces to Mozambique in the face of the rising Islamist insurgency in northern Cabo Delgado province.3

While Rwanda has increased involvement in regional security alongside host governments, since 2022 the bulk of its regional interventionism has shifted toward supporting the March 23 (M23) rebel movement in fighting Congolese military forces (FARDC) and allied militias in the Democratic Republic of Congo (see map below). Although Rwandan troops have carried out low levels of civilian targeting across the continent as a proportion of their total operations in multilateral and bilateral operations, the DRC case shows the increased risks to civilians due to Rwanda’s rising use of artillery shelling and equipping of proxy fighters — a growing concern in the Great Lakes Region.4

While several other reports consider Rwanda’s involvement in multilateral operations, this piece examines how Rwanda’s foreign military operations have changed since 2020, drawing on case studies from bilateral operations in Mozambique and unilateral deployment into DRC in support of the M23 rebel group. The case of Mozambique illustrates the RDF’s capacity to support counter-offensives against competing armed groups and suppress levels of violence, but with limited ability to curb civilian targeting from other armed groups, as was the case in CAR. The RDF involvement in Mozambique also illustrates the forms of Rwandan bilateral operations in Africa, including engagement in security, economic activity, and politics. Like its bilateral and multilateral deployments, the RDF’s presence in the DRC provides Kigali with economic benefits obtained by controlling strategic roadways and mining sites.

The growth of Rwandan foreign security engagement

After Rwanda deployed forces into neighboring Zaire — now the DRC — during the Congo Wars from 1996 to a blurry conclusion in 2002, Rwanda turned toward contributing troops and additional personnel for multilateral deployment. Since 2004, Rwanda has increased its deployment to multilateral peacekeeping missions,5 with growing numbers of troops deployed to UN and African Union missions. Rwanda’s foreign security deployments also grew to include bilateral missions in 2020, building international legitimacy as a cooperative partner for multinational security operations. The deployment and deeper integration into peacekeeping and bilateral missions spanning the continent provide political leverage for Kigali, economic resources, and strategic training for Rwandan personnel.6 Further, Rwanda funds a substantial portion of the national defense budget through contributions from UN peacekeeping missions. Bilateral missions in CAR and Mozambique also provide considerable commercial opportunities for Rwandan firms, some of which are reported to have links to President Paul Kagame’s ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).7 For the past 30 years, several large firms owned fully or partly by the ruling RPF developed under party management and expanded into many sectors of the economy.8

The growth of unilateral operations and indirect support for the M23 has generated tensions between Rwanda and several Western countries — often the same countries supportive of and reliant upon Rwandan peacekeeping contributions.

Alongside bilateral and multilateral operations, Rwanda deployed troops to the DRC and has increased its military engagement amid the latest M23 offensive. The growth of unilateral operations and indirect support for the M23 has generated tensions between Rwanda and several Western countries — often the same countries supportive of and reliant upon Rwandan peacekeeping contributions. The Rwandan government now balances the criticism and threats for its involvement in the DRC with its contributions to peacekeeping operations, with mixed reception of its bilateral operations. In several instances, Kigali used its position as a significant troop contributor to counter foreign criticism, threatening to withdraw peacekeepers from multilateral missions.9

Spokespersons for Kigali have yet to admit direct military involvement or support for the M23. Instead, Kagame and other Rwandan political leaders increasingly deflect critics’ questions by responding with rhetorical questions that allude to reasons Rwanda’s involvement in the DRC would be warranted. They cite threats to domestic and regional security, including continued operations of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) and their collaboration with FARDC, military buildup in Congo, Congolese political rhetoric to invade Rwanda, and violence against Congolese Tutsi.10 Kagame and other Rwandan officials have also noted the colonial construction of the country’s borders, remarking that this part of eastern DRC was formerly part of Rwanda.11

For those more critical of Rwanda’s actions, the threats of the FDLR claimed by Kigali are simply a false pretext for Rwanda to continue exerting its economic and political influence in eastern DRC.12 While various studies have long signaled the smuggling of resources from the DRC into Rwanda and other regional neighbors,13 Congolese officials increasingly point to these resource interests and Kigali’s desire to annex part of eastern DRC as motivation for Rwanda’s renewed involvement.14 The replacement of local government officials with M23 militants and supporters throughout areas of North Kivu also provides evidence of Rwandan and M23 interests in local political power.15

Still, increasing sources of drone footage and eyewitness photography of Rwandan soldiers and heavy military equipment in the DRC make denying Rwandan military presence more difficult.16 According to recent estimates, Rwanda deployed around 3,000 soldiers to the DRC — primarily operating alongside the M23 — with further provision of training and equipment for rebel fighters.17

Rwanda’s military operations abroad

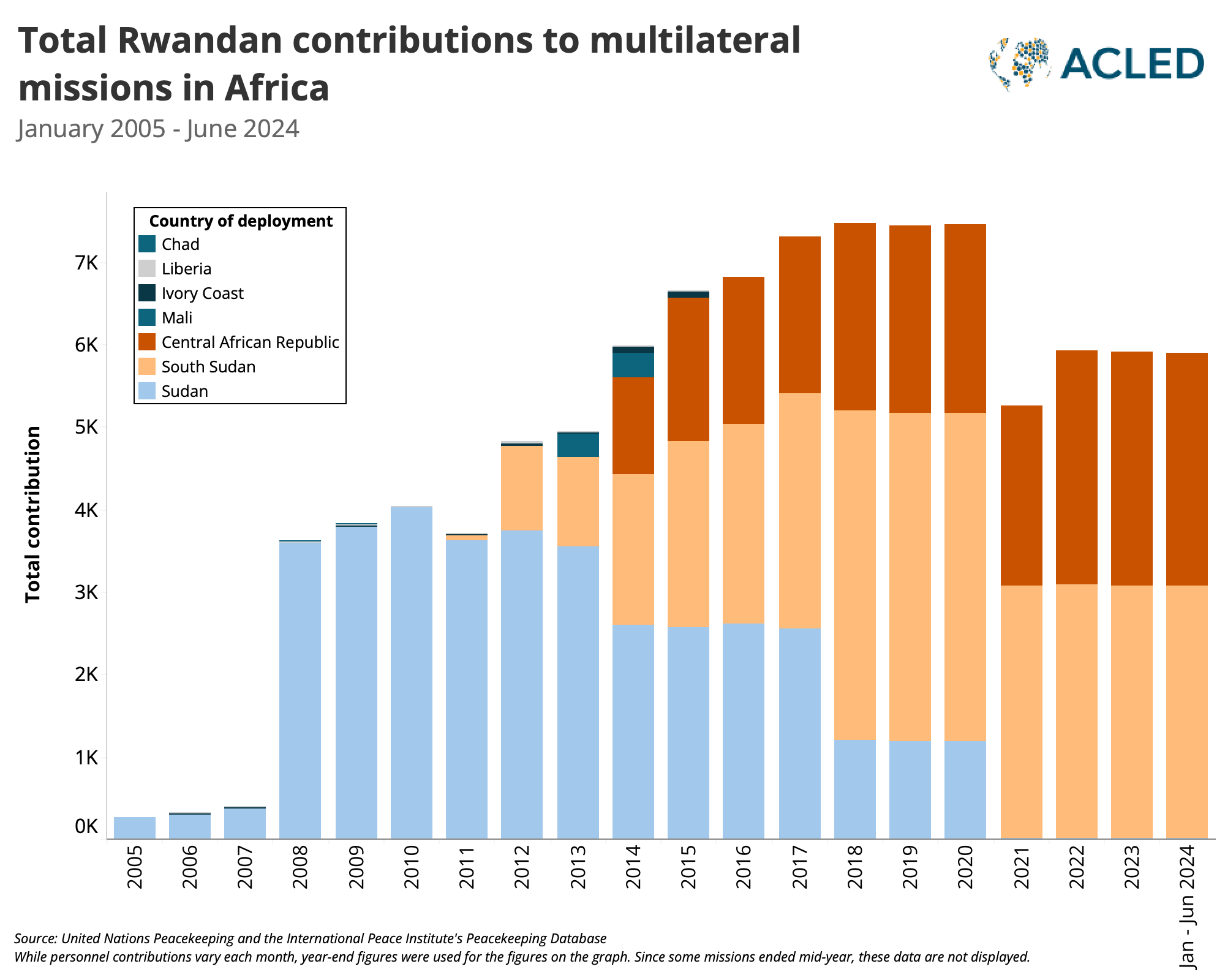

Multilateral operations

In the aftermath of Rwanda’s involvement in the Congo Wars, Kigali began a process of increasing involvement in multilateral engagements. From 2004 onward, Rwanda’s contribution to peacekeeping efforts permitted Kigali financial and material benefits for their relatively large and experienced military — a considerable workforce to employ following over a decade of conflict, along with a shifting international perception of Rwanda as a stable country with capacity for international investments.18 Rwandan military and political spokespeople tend to point back to the failures of international peacekeeping efforts in Rwanda to underline the need for African troop contributions to multilateral missions.19 Kigali has since grown to become one of the world’s largest contributors of peacekeeping personnel.20 Beginning with a peacekeeping deployment of just 150 soldiers with the AU Mission in Sudan (AMIS) in 2004, by March 2024, Rwanda ranked as the fourth-largest contributor of UN peacekeeping personnel globally and the largest in Africa, with 5,894 personnel.21 Rwanda’s contributions to peacekeeping missions have spanned several countries in Africa (see graph below).22 The type of personnel for these multilateral missions varies and includes police, soldiers, and advisers.

In CAR, Rwanda has grown to be the largest troop contributor for the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), making up nearly 20% of peacekeeping forces as of 31 March 2024. Rwanda provides MINUSCA with around 2,100 soldiers, 700 police, and 30 additional staff officers, led by Rwandan commissioner Christophe Kabango Bizimungu.23 While reporting does not allow for differentiation between Rwandan or non-Rwandan peacekeepers, violent engagement through multilateral missions in CAR has been focused on battling armed groups, making up 80% of violent peacekeeping events involving MINUSCA since 2013.

Bilateral deployments

Although Rwanda continues to increase its peacekeeping contributions, numerous countries in Africa are drawing down or expelling multilateral operations and looking for alternative security partners.24 Bilateral military agreements often move faster and offer more flexibility than multilateral peacekeeping missions with numerous stakeholders.25 Several actors, including private military companies and foreign militaries, have been willing to fill the security gap left by multilateral peacekeeping missions in Africa. Aside from occasional joint endeavors with military forces in the DRC, Rwandan bilateral military operations began in earnest with the deployment of hundreds of soldiers to CAR to counter a rebel offensive in late 2020.26 Rwanda further expanded bilateral deployments in July 2021 by sending 1,000 soldiers to Mozambique during escalating violence involving Islamist insurgents in the northern Cabo Delgado province.27

Bilateral missions provide Kigali and host governments with more flexible mandates for military engagement than AU or UN peacekeeping missions, allowing for a wider range of operations and partnerships.

Rwanda’s bilateral military policy combines political, security, and economic engagement to further the country’s foreign policy.28 Following Rwanda’s bilateral deployment to CAR and Mozambique, numerous Rwandan businesses were started in the host countries with tax-break incentives and agreements over land and mineral rights, diversifying Rwanda’s domestic dependence on agriculture.29 Missions abroad also generate foreign revenue as host governments pay for troop deployment in foreign currency or in exchange for natural resource rights.30 Since 2020, Rwanda has expanded its number of embassies, increased the number of diplomatic visits undertaken by its top officials, and formed socioeconomic cooperatives for Rwandans living abroad.31 In areas of security, Kigali has long maintained an interest in securing threats from neighboring countries and uses an extensive foreign intelligence network.32

Bilateral missions provide Kigali and host governments with more flexible mandates for military engagement than AU or UN peacekeeping missions, allowing for a wider range of operations and partnerships. Peacekeeping mandates tend to restrict operations to a more defensive security posture and are focused on protecting civilians.33 The bilateral mandates have also resulted in various security partnerships with the RDF and allied actors. In CAR and Mozambique, the RDF has operated alongside the host country’s military forces but overlapped with multilateral forces. Rwandan troops joined operations alongside UN peacekeepers in CAR and Southern African Development Community (SADC) troops in Mozambique.34 In CAR, Rwandan special forces also fought alongside Wagner Group mercenaries during counter-offensives against rebel groups. During the initial counter-offensive in CAR from December 2020 through May 2021, Wagner Group mercenaries and military forces — allies of the RDF — attacked civilians more frequently than they clashed against rebel groups. Eventually, Rwandan special forces ended joint operations with Wagner Group, citing human rights concerns and violence targeting civilians.35

Unilateral interventions

Alongside cooperation with partner governments during multilateral and bilateral missions, Rwanda has also engaged in several unilateral operations since the Congo Wars. According to ACLED data, with coverage that dates back to 1997, 92% of violent events carried out by the RDF during unilateral deployments have taken place in the DRC. These military excursions into Rwanda’s western neighbor began with deep involvement in the Congo Wars as it pursued former Rwandan political leaders and fighters from the previous regime.36 Violent incidents involving Rwandan military forces during unilateral deployments decreased in the early 2000s, yet Kigali maintained involvement in the DRC through support for armed groups and occasional direct military operations.37

Aside from the DRC, Rwanda has also had occasional skirmishes on the borders with Burundi and Uganda. Between 2019 and 2022, several cases of violence broke out when the RDF fought with military forces in Uganda near their shared border during a tense period as the two countries traded accusations of supporting political dissidents and undermining security.38 Similarly, in June 2022, the RDF carried out a multi-day offensive into Burundi against armed groups in the border Kibira Forest region. This frontier violence between military forces, proxy warfare, and inflammatory rhetoric has often soured relationships between Rwanda and other countries in the Great Lakes region. The strained relations led to several border closures, constrained civilian mobility, and limited commerce with Rwanda’s neighbors.39

Bilateral deployment to Mozambique (2021-)

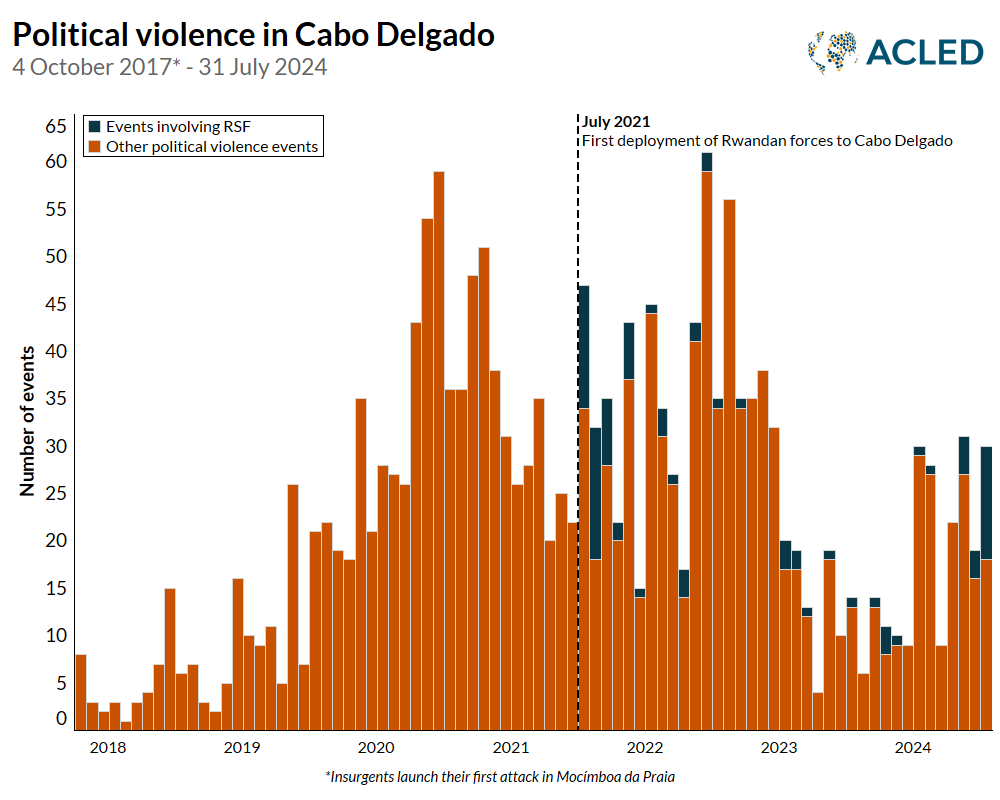

At the invitation of the host government, Rwanda deployed RDF troops and a smaller police contingent to the Cabo Delgado province of northern Mozambique in July 2021. The deployment followed a July 2021 attack by the insurgent group now known as Islamic State Mozambique (ISM) on Palma town in March 2021.40 The attack was the culmination of a series of ISM actions targeting towns in the province over the previous 12 months, indicative of the state’s loss of control in the province, which led to the suspension of a nearby liquefied natural gas (LNG) project led by French oil giant TotalEnergies.41 The RDF engaged immediately with the insurgents, with nearly 27 reported battle events between the RDF and ISM in the first two months of deployment.

The deployment to Mozambique, built on several years of enhanced bilateral relations between the two countries, followed a similar strategy to the deployment to CAR. The well-developed diplomatic relationships in both countries enabled rapid bilateral deployment when the interests of both the host country and Rwanda aligned. In the case of Mozambique, relations between President Paul Kagame of Rwanda and President Filipe Nyusi of Mozambique and their respective administrations developed positively over the previous eight years, starting with President Kagame’s visit to Mozambique in 2016, which led to cooperation agreements in various sectors and a commitment to establish a Joint Permanent Commission (JPC) between the two countries. The JPC, which acts as a mechanism for formal exchanges at technical and political levels in areas of common interest, was established two years later.42

With bilateral relations strengthened, Rwanda was well-placed to deploy when the need arose in July 2021. The positive relationship between the two presidents facilitated navigation through a complex set of interests around the Cabo Delgado conflict. These included the interests of the SADC, which had been publicly pushing for military intervention since May 2020 due to regional security concerns, and of France, with its interest in the LNG project led by TotalEnergies.43 In the wake of the suspension of the LNG project, President Nyusi sought Rwandan intervention. In April 2021, just days after the project was suspended, President Nyusi visited Kigali to discuss possible intervention. The following month, at the Summit on Financing African Economies in Paris, he met with President Emmanuel Macron, who spoke of his interest in supporting Mozambique in the fight against “terrorism.”44 By the end of May 2021, a Rwandan reconnaissance team was in Cabo Delgado, while the first 1,000 soldiers had been deployed in Cabo Delgado province by July of the same year.45

Impact of deployment

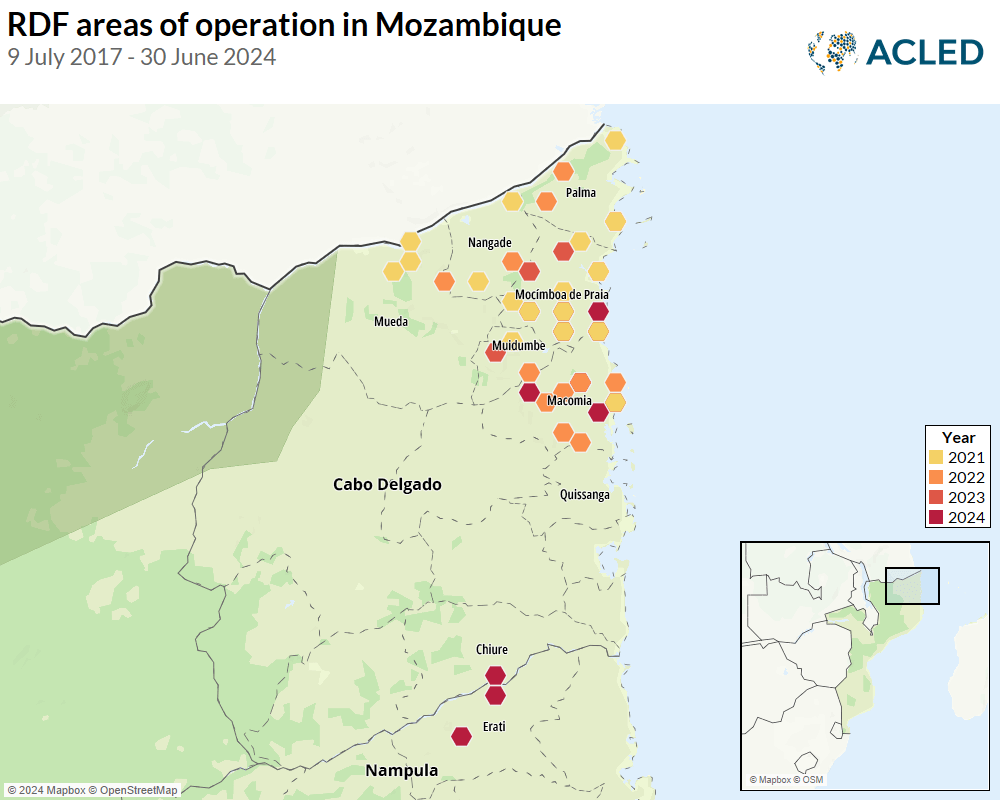

The RDF initially deployed to Palma, first around the LNG plant on the Afungi peninsula near Palma town. Operations in 2021 were concentrated in the Mocímboa da Praia district, reflecting the fight for the recapture of the port and the move against insurgent bases south of the town. Less intense operations across a further five districts that year reflected the pursuit of ISM fighters. In 2022, operations declined by over two-thirds. Though spread across six districts, over 80% of recorded events involving the RDF were in Macomia district, reflecting ISM’s move to the hard-to-access Catupa forest in response to RDF operations — as well as those by the multilateral SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) — and the economically strategic districts of Mocímboa da Praia and Macomia. Notably, its only permanent presence outside Mocímboa da Praia and Palma districts from 2021 to 2023 was a small base in the Ancuabe district, just 10 kilometers from the main highway linking Pemba, the provincial capital, with the north of the province, as well as with gemstone and graphite mines to its west.46 Operations in 2023 were almost entirely concentrated in the Mocímboa da Praia district but with notable clashes in Nampula province, the first time the RDF operated outside Cabo Delgado province (see map below).

The RDF’s approach in Mozambique has focused on securing strategic economic projects and operational independence. RDF infantry operations in Mozambique are notable for their emphasis on protecting civilians. Only two incidents of violence targeting civilians have been recorded since 2021. Rwandan military doctrine privileges civilian protection in peacekeeping operations. Rwanda’s central role in the adoption and promotion of the Kigali Principles on the Protection of Civilians helps explain this.47 The principles encourage a counterinsurgency posture that seeks community engagement in patrolling practices and restraint in combat in peacekeeping operations.48

However, the withdrawal of SAMIM forces in 2024, along with the subsequent increasing reliance on air support, is likely to result in a more aggressive approach to ISM, potentially compromising Rwanda’s commitment to civilian safety. This defensive posture began to shift in 2024, not long after SAMIM troops were withdrawn. In May 2024, RDF troop numbers increased from approximately 2,500 to around 4,000. Up to that point, operations had been conducted with minimal collaboration with SAMIM, which deployed soon after the arrival of the RDF.49 Over 2021, 2022, and 2023, ACLED records just seven joint RDF-SAMIM operations, a figure that reflects an unpublished assessment by the government of Mozambique.

As deployment has expanded, incidents involving the RDF have increased significantly. ACLED data show that RDF operations had more than doubled by mid-August compared to all of 2023 (see chart above). This has been accompanied by a change in tactics. In the first half of 2024, combat helicopters were deployed and first used in July and August of that year in operations against ISM positions along the Macomia coast and inland in the Catupa forest. In 2024, the first Rwandan operations took place in the south of the province, in the Chiúre district and the Eráti district of neighboring Nampula province. Thus far, the change in tactics and wider geographic scope of operations has not resulted in any increase in civilian targeting.

The political economy of deployment

Rwanda’s overseas deployments are costly. In 2023, the mission in Mozambique was estimated to cost up to $250 million per year when it numbered approximately 2,000 troops.50 There are now almost 4,000 in the country. President Kagame has stated that the operation is largely self-funded.51 Rwanda received additional financial support for the operation from the Council of the European Union, which approved 20 million euros in December 2022.52 Renewal of this support in 2024 has met resistance in some European capitals and has consequently been delayed.53 Supporting commercial engagement by Rwandan firms can indirectly ameliorate such costs. Overseas operations in Mozambique also allow for Rwanda’s own political and security interests to be addressed.

One Rwandan firm has won a contract to provide security at the LNG project site in Palma district. Securing the site and wider district was a significant, and likely primary, objective of the RDF. In 2021, almost 10% of Rwandan violent engagement was in Palma district, rising to over 20% in 2022. None has been recorded since. The security company is controlled by Crystal Ventures, a Rwandan Patriotic Front-associated holding company.54

Another Rwandan-led firm has been established to explore for graphite, which was found around Ancuabe, where the RDF has a small base. This firm is also reportedly associated with Crystal Ventures.55 Though RDF actions have not been recorded in Ancuabe district itself, Ancuabe is the operating base for operations in Chiúre and Eráti districts. Over 14% of Rwandan actions in 2024 have been in those two districts. There are also more domestic benefits. In January 2022, TotalEnergies agreed to open a permanent office in Rwanda and collaborate in the renewable energy sector there.56

Kigali also pursues several political interests in Mozambique. In 2024, Mozambique approved an extradition agreement with Rwanda, a development that the Mozambique Law Society says is linked to Rwandan concern over the presence of Rwandan opposition figures in the country.57 Counterinsurgency in Mozambique is directly relevant to Rwanda’s security. Since its inception, the insurgency in Mozambique has been connected to violent jihadist networks across East Africa.58 Over the years, this has grown into a formal and active relationship with Islamic State and its affiliates in the region. Although ACLED does not record any Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) violence in Rwanda, ADF cross-border violence into Uganda doubled in 2023 compared to the previous year. Kigali could perceive the ADF’s growing cross-border activity as a threat to its security, and involvement in Mozambique improves access to intelligence about these networks.

Unilateral operations and rebel coalitions in the DRC since 2022

The RDF’s direct involvement in eastern DRC rose in 2022 in conjunction with an offensive launched by the M23 rebel group in North Kivu. The UN Security Council estimates that Rwanda has deployed between 3,000 to 4,000 soldiers to the DRC, operating alongside M23 rebels.59 Rwanda’s intervention in the DRC has likewise grown over time. ACLED data show that events involving the RDF in the DRC grew from an estimated 60 in 2022 and 2023 combined to over 150 violent events in the first six months of 2024.60

The relationship between Kigali and Kinshasa since the First Congo War began in 1996 has been ambivalent, swinging between cooperation and competition. On several occasions, Congolese military forces have collaborated with the RDF. For example, they participated in a joint operation in 2009 against the FDLR61 — a rebel group that now has integrated several factions but traces its roots to the Interahamwe, a Hutu militia that initially carried out violence in Rwanda before fleeing to the DRC, and former Rwandan soldiers from the previous regime. However, relations have also turned conflictual several times. After the Rwandan military’s initial support for former President Joseph Kabila to take over the DRC from Mobutu Sese Seko, relations deteriorated as Kabila sought to consolidate sovereign control over the country and pushed Rwandan troops out in July 1998.62 Instead of expulsion, Rwanda launched renewed offensives into the DRC against the Kabila regime, clashing with military forces under the regime Rwanda had just helped install. While reaching peace agreements in 2002, fragile relations ruptured. The origins of the M23 date back to the challenges of integrating Rwandaphone militants during the conclusion of the Congo Wars.63 A rebel group and precursor of the M23 eventually formed, called the National Congress for the Defence of the People, with Rwandan government support and under the leadership of a former RPF militant, Laurent Nkunda.64 Later, Rwanda’s support of the M23 rebel group during their offensive in the DRC’s east in 2012 saw the capture of the North Kivu provincial capital, Goma.65

The RDF’s involvement in the M23 conflict

As has been the case since the Congo Wars, the majority of the RDF’s engagement in violence since 2022 has involved battles against other armed groups — comprising 81% of total violent events. More than 90% of RDF operations in the DRC between 2022 and 30 June 2024 were carried out with the M23, with additional partnerships including the Congo River Alliance — a rebel group formed in late 2023 and headed by the former president of the DRC’s electoral commission, Corneille Nangaa.66

ACLED records 20 cases of the RDF targeting civilians between 2022 and the first six months of 2024, resulting in over 45 reported fatalities, but over half of these events took place in 2024. While the RDF has been more careful to guard against civilian targeting during multilateral and bilateral deployments, civilian targeting now accounts for 10% of its total political violence in the DRC.

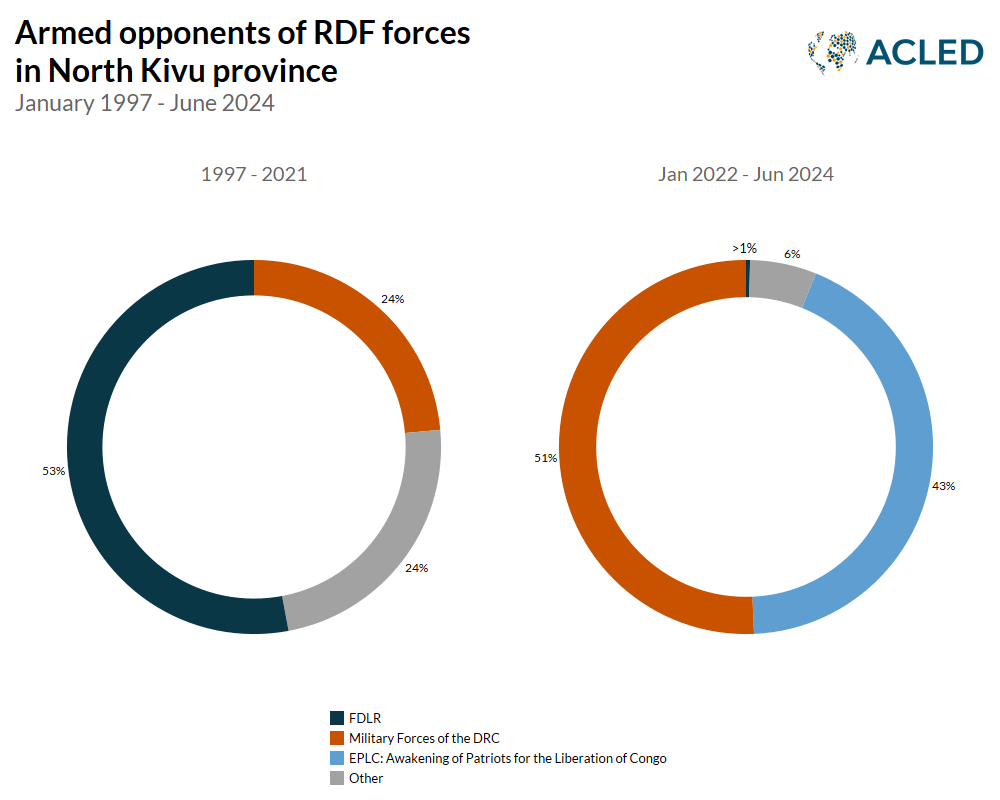

While the primary type of violence in the form of battles remains broadly consistent over time, the primary opponent to the RDF has dramatically changed (see graph below). As far back as the Congo Wars, Rwanda’s military primarily engaged with a number of rebel groups, militias, and other foreign militaries. While previous incursions have rarely seen the RDF involved in clashes with Congolese military forces, Rwanda’s primary opponents since 2022 have been FARDC and allied forces such as the Wazalendo. During this time, the RDF has seldom engaged in violence against rebel groups or militias aside from allied groups fighting with FARDC. Despite the political rhetoric against the FDLR, the RDF has not engaged directly with the FDLR since a single operation in late May 2022.67

In addition to clashes with military forces and allied groups, Rwanda has increasingly been using shelling and artillery strikes in the DRC. Remote violence events involving the Rwandan military and M23 especially increased in the first half of 2024. A growing number of reports detail Rwanda’s provision of heavy weapons to M23, including drones, anti-drone jamming equipment, surface-to-air missiles, and anti-tank grenade launchers.68 Rwanda claims that the Congolese import of fighter drones and violations of Rwandan airspace require that Rwanda ensure its air defenses, serving as an indirect justification for the recent rise in remote violence.69

Amid the rise in remote violence, civilian targeting by the RDF has also escalated, driven by increased shelling into civilian-populated areas. ACLED records 20 cases of the RDF targeting civilians between 2022 and the first six months of 2024, resulting in over 45 reported fatalities, but over half of these events took place in 2024. While the RDF has been more careful to guard against civilian targeting during multilateral and bilateral deployments, civilian targeting now accounts for 10% of its total political violence in the DRC. The RDF provision of more advanced weapons systems to the M23 has also resulted in a rising civilian toll. Civilian targeting through remote violence by the M23 — without direct collaboration with the RDF — rose from just six events in 2022 and three events in 2023 to 34 events in the first six months of 2024. Thus, the RDF’s direct military involvement in the DRC not only poses further threats to civilians but increased risks through indirect support for M23 rebels.

Squeezing Goma: Rwandan economic interests across the border

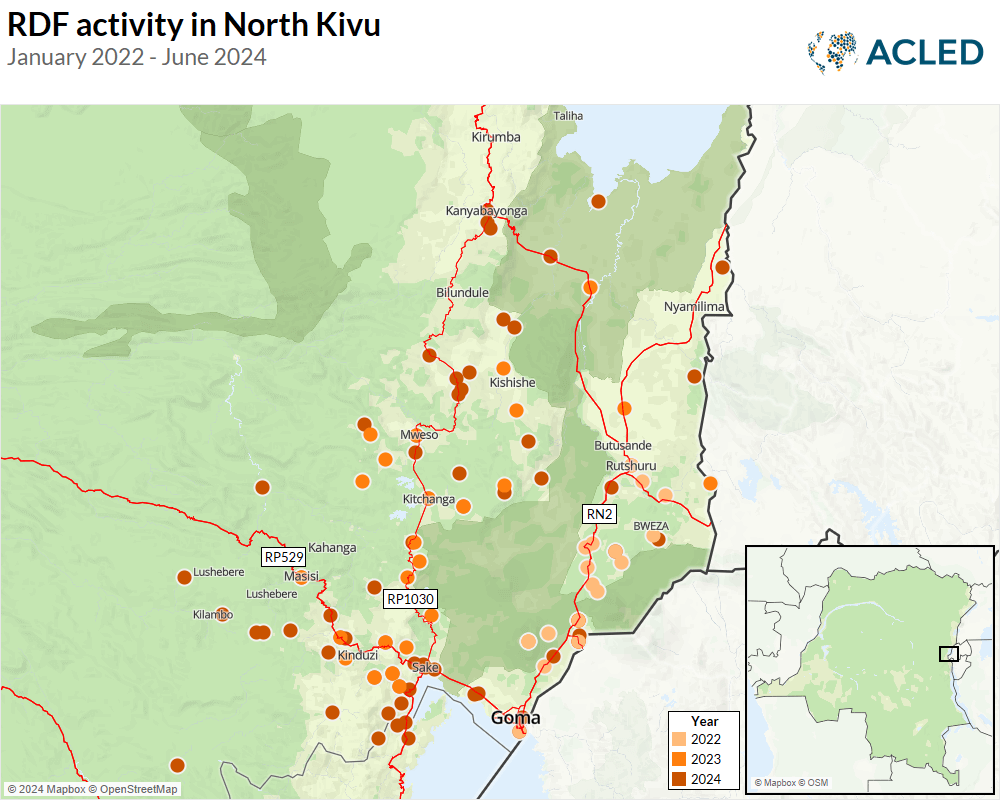

Since 2022, the RDF has sought to surround Goma and gain control of the major roadways to the regional capital. The contestation and control over these areas have severely limited military supplies and the flow of economic goods to Goma, permitting the M23 and RDF to extract revenues from imposing roadblocks along roadways and accessing mining sites.

With M23 fighters, the RDF gained control of sections of each major road linking Goma with the rest of the North Kivu region. The concentration along these roadways has especially been the case in 2023 and so far in 2024, as 48% of political violence events involving the RDF took place along the three major roads out of Goma via Sake. The M23 and RDF control of roadways also extends to other areas, such as the stretch of road between Rutshuru and the border town of Bunangana. The M23 and RDF secured several positions along this roadway in 2022, with estimated earnings of US $27,000 per month.70

The movement of the RDF and support for M23 permitted the capture of several roadways and mining areas. In 2022, RDF offensives initially focused on the border region of Rutshuru, just across from northwestern Rwanda (see map below). In 2022, 67% of violent engagement took place in Rutshuru territory, followed by 29% in Nyiragongo territory — important areas of resource supply chains and links to the regional hub of Goma city along the RN2 (Rutshuru-Goma) roadway. In 2023, direct violence by the RDF began shifting to Masisi territory, a resource-rich area with three major interior roadways out of Goma via Sake. These roadways include the RP1030 (Sake-Kitchanga-Kanyabayonga), which provides the only major alternative route to the RN2 northward toward Ituri province; the RP529 (Sake-Walikale), a key route into the interior from Sake to Walikale that connects to the RN3 (Bukavu-Walikale-Kisangani); and along the southbound RN2 (Sake-Miti) from Sake toward Bukavu which is home to large reserves of coltan.71 So far in 2024, the RDF has increasingly moved toward Goma alongside M23 fighters, cutting off several sections of the roads near the city — especially around Sake. The busy Sake-Kilolirwe-Kitshanga road axis has an estimated revenue generation of $69,500 per month just in vehicular taxes.72

The making of a regional security actor

The space for multilateral peacekeeping will likely shrink in the coming years, with several peacekeeping drawdowns completed or in progress in Africa. Rwanda will likely continue to make peacekeeping contributions that provide it with strategic diplomatic and economic advantages. These are especially useful while Kigali faces mounting criticism over the violence in North Kivu. However, multilateral operations in Africa may continue at a smaller scale in the form of more regional agreements, such as the recent use of the East African Community or SADC mission in Mozambique.

Following peace agreements between Rwanda and the DRC for a ceasefire beginning 4 August 2024, political violence involving the RDF may diminish in the coming months. Past peace agreements have temporarily limited violence but have yet to effectively generate a durable solution to the contestation.

Although multilateral operations are poised to decline in the future, Rwanda already plans to send an additional 2,000 troops to support its bilateral mission in Cabo Delgado. In 2024, the joint forces have faced increasing violence from insurgents compared to 2023.73 The RDF may face further pressure as SAMIM continues to withdraw troops from Mozambique this year. New opportunities for bilateral deployments may also arise in the near future. As other states in coastal West Africa face threats from insurgent groups,74 Rwanda is strategically positioned to expand bilateral military agreements in the region. Benin and Rwanda have already begun discussions for RDF deployment and logistical support to combat insurgent violence in northern Benin.75 Rwanda may fill a key security space for countries disillusioned with Western or multilateral security partners but unwilling to pivot toward Russian private military options.

Following peace agreements between Rwanda and the DRC for a ceasefire beginning 4 August 2024,76 political violence involving the RDF may diminish in the coming months. Past peace agreements have temporarily limited violence but have yet to effectively generate a durable solution to the contestation. Shortly after the ceasefire announcement, M23 announced it was not part of the agreement, suggesting the rebels may continue operations.77 With expansion southward into South Kivu and ongoing contestation around Goma, the violence is poised to escalate throughout the year if the peace agreements fail to provide tangible results. Further, if the M23 and RDF take over Goma, or their economic constraints on strategic roads and supply routes are sufficient to force negotiations between Kinshasa and Kigali, the violence would likely crescendo and decline. This escalation and swift end to violence involving the M23 took place in 2012, shortly after the M23 captured Goma, which forced negotiations and a peace plan with the conflict parties.78 Despite ongoing Rwandan operations in the DRC, further unilateral deployments in the Great Lakes are improbable. Skirmishes with rebel groups and border security in Burundi or Uganda are unlikely to escalate further despite diplomatic tensions.

The examination of Rwanda’s foreign military engagement illustrates the country’s shifting standing in Africa and beyond. The multilateral and bilateral deployments in the DRC and Mozambique have generally strengthened Rwanda’s status across the continent as a regional security force, bolstering diplomatic relations with the international community, working toward African integration, and pushing back against non-African interventions.79 Yet, Rwanda’s deployment into the DRC has strained relations with Kinshasa, Gitega, and Western governments. Burundi and Rwanda’s borders remain closed with frequent critical rhetoric,80 amid growing Western hesitation to renew support for Rwandan military operations.81 Rwandan support for the M23 may have strained numerous diplomatic relations,82 but the growing security gap in Africa and threat of Russian influence will likely continue to make the RDF a preferred alternative for multilateral and bilateral military cooperation in the region.

Visuals produced by Christian Jaffe.

Contents

- Introduction

- The growth of Rwandan foreign security engagement

- Rwanda’s military operations abroad

- Bilateral deployment to Mozambique (2021-)

- Unilateral operations and rebel coalitions in the DRC since 2022

- The making of a regional security actor

Ladd Serwat

Ladd Serwat is an Africa Regional Specialist at ACLED. Ladd has been with the organization since November 2018, originally hired as an Africa researcher. He is involved in team management, data review, and analysis, as well as project representation. Ladd holds a PhD in International Development from the University of Sussex, an MSc in African Development from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and a BA in International Relations from Gonzaga University. Ladd has over 10 years of experience working with different non-profit organizations and a particular research interest in land-related conflict.

Peter Bofin

Peter Bofin is a Senior Research Coordinator with ACLED, focusing on the Cabo Ligado conflict observatory for northern Mozambique.