Starvation was the leading cause of death across all ages in the study group. This reflects an expedited humanitarian response from aid agencies to prevent more deaths. Interventions, including the return of the displaced communities to their original homes, are needed to rescue those facing moderate to severe hunger.

Source: BCM Public Health

- Mekonnen Haileselassie,

- Hayelom Kahsay,

- Tesfay Teklemariam,

- Ataklti Gebretsadik,

- Ataklti Gessesse,

- Abraham Aregay Desta,

- Haftamu Kebede,

- Nega Mamo,

- Degnesh Negash,

- Mengish Bahresilassie,

- Rieye Esayas,

- Amanuel Haile,

- Gebremedhin Gebreegziabiher,

- Amaha Kahsay,

- Gebremedhin Berhe Gebregergs,

- Hagos Amare &

- Afework Mulugeta

BMC Public Health volume 24, Article number: 3413 (2024) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

People in war-affected areas are more likely to experience excess mortality with hunger. However, information on the causes of death associated with hunger is often nonexistent. The purpose of this study was to verify and investigate hunger and hunger-related deaths after the Pretoria deal in Tigray, northern Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in nine districts and 53 IDP sites, which were randomly selected. All households with deceased family members were included and screened for perceived causes of death between November 2, 2022, and August 30, 2023. Suspected starvation deaths were further verified by the WHO-adapted verbal autopsy questionnaire to establish cause-specific mortality. Using a standardized cause-of-death list, three physicians assigned the causes of death, and disagreements over-diagnoses were settled by consensus. The Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance guidelines were also used to quantify household hunger status.

Results

Verbal autopsies were conducted for 72.2% (1946/2694) of deaths. Of these deaths, 201 (7.5%) in under-five children and 1205 (44.7%) in females were recorded. Deaths increased from 8.6% in March to 16.4% in July. A total of 90.6% of deaths occurred at home. Starvation was the predominant cause of death across all ages (49.3%, n = 1329). About 94/155 (60.3%) in the IDP center and 1235/2539 (48.6%) in the community died due to starvation. Children under five had a higher risk of starvation-related deaths (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.22–2.34). Females were also more likely to die by starvation than males. Large proportions of households (60.1%) had moderate or severe hunger.

Conclusion

Starvation was the leading cause of death across all ages in the study group. This reflects an expedited humanitarian response from aid agencies to prevent more deaths. Interventions, including the return of the displaced communities to their original homes, are needed to rescue those facing moderate to severe hunger.

Background

Hunger and undernutrition are the greatest threats to public health, killing more people than HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined [1]. Globally, about 735 million people faced hunger in 2022 [2]. Each day, 25,000 people, including more than 18,000 children, die from hunger and hunger-related causes [1]. Nearly 98% of worldwide hunger exists in underdeveloped countries and Africa takes the biggest share (20%), followed by Asia (8.5%) [2, 3]. Focusing on East Africa, hunger is expected to claim one life every second [1]. This is in contradiction to the fundamental right of human beings to have access to adequate food and the international law binding all nations to keep their citizens free of hunger [4, 5]. Moreover, it also erodes the global commitment to end hunger by 2030 [6].

Regrettably, this deprivation is not because of insufficient food production. But people are getting starved to death, with women and children paying the highest price, in the world of plenty, owing to uneven distribution and poor access to food while weather extremes, the COVID-19 pandemic, and spiraling food prices all contribute; armed conflict is the main cause of hunger and malnutrition [7, 8].

In many places, conflict and hunger are intertwined, one reinforcing the other, forming a vicious cycle that is hard to break [9]. Conflict precipitates hunger in many ways, all of which were apparent in the war on Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Fighting disrupts environmental security and hinders access to farmland and food production [10]. It also prevents access to markets and interferes with the flow of commercial food commodities and humanitarian aid, limiting access to sufficient food suppliesm [11, 12]. Combatants to the fighting burn harvest steal or slaughter livestock, intentionally loot and/or destroy food stocks, seed crops, and other productive assets [9, 10, 12, 13]. Warring parties systematically cause mass displacement of civilians by burning their houses and properties [10, 14]. Moreover, hunger is a weapon of war through the deliberate killing of humanitarian workforces and the blockade of humanitarian corridors [11, 15]. Conversely, hunger can also lead to violence and fuel conflict. For instance, displacement could result in straining over the resources of the host communities and cause tension and violence [10].

Given that the link between conflict and hunger is multidimensional, it is essential to ensure a strong nexus between humanitarian assistance, development, and peace-building activities to break this cyclical relationship and sustainably rehabilitate the community [16]. Specifically, regarding the situation in Tigray, the cessation of hostilities occurred following the signing of the Pretoria peace deal on November 2, 2022, between the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), marking a significant milestone [17].

However, the effort to sustain this peace accord through humanitarian assistance and high-impact developmental interventions to transform the livelihood of the community is meager. There was a noticeable delay in the resumption of aid; the flow after resumption was infrequent and inadequate; the distribution process was tardy; and since April 2023, there has been a complete aid suspension over allegations of aid diversion [18, 19]. Altogether, the post-war engagement is insufficient to address the food shortage legacy of the active fighting. Hence, hunger is continuing in its worst form, and death reports are mounting concerning it.

Referring to Tigray’s Disaster Risk Management (DRM) Commission, Addis Standard [20], Reuters [21], Associated Press (AP) [22], and The Telegraph [19] have reported hunger deaths among more than 700 people. Unpublished research findings from Mekelle University also uncovered 165 deaths in seven internally displaced people (IDP) camps [19]. The claimed death rate is understated in light of the following reality on the ground. Ethiopia as a nation is in a state of serious hunger as per the global metric (GHI 27.6, ranking 104th out of the 121 countries) [23]. The war on Tigray has left 5.4 million people food insecure, with a considerable number of them in a reportedly famine-like condition [22]. A recent systematic study conducted by the Tigray Health Research Institute (THRI) discovered severe food insecurity being pervasive in two-thirds of households (66.9%), with half of the households (50.1%) having no food to eat at home. Moreover, 38% of the under-five children studied were acutely malnourished, with severe acute malnutrition ensuing in 9.2% of them [24]. Overall, surpassing the 15% Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) rate as a threshold for a widespread emergency and the 18% point increase (from 10% in 2019 to 28% in 2022) in children of Tigray [25], we expect more hunger deaths to unfold.

Generating the hunger death statistics will be useful in updating the international community about the food and nutrition security status of the community to influence the aid agencies toward the resumption of humanitarian aid and other pertinent services essential to the debilitated community.

Therefore, the objective of this study was two-fold:

- 1.Verify and investigate hunger and hunger-related deaths among the study communities.

- 2.Explore the community level of risks for death due to hunger.

Methods and materials

Study area

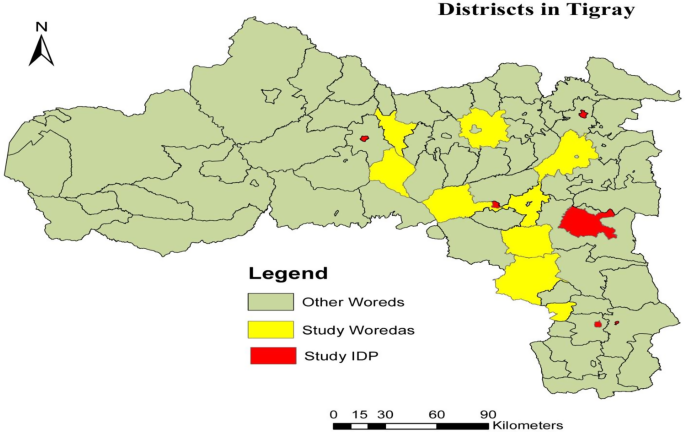

The study was carried out in nine woredas, namely, Bora, Samre, Seharti, DeguaTemben, Quolatemben, Rural Hawzien, Rular Adwa, Zana, and Laelay Qoraro. All IDP centers in Maichew, Mekelle, AbiAdi, Adigrat, and Shire were also part of the study setting (Fig. 1). More than five million people reside in the region, with rural inhabitants constituting 81.5% of the total population. The region has 1,165,575 households (HH), averaging 4.4 persons per household; this includes 3.4 persons per household in urban areas and 4.6 persons per household in rural areas. Prior to the conflict, the region had 712 health posts, 214 health centers, and 38 hospitals, which comprised one specialized hospital, fifteen general hospitals, and twenty-two primary hospitals. Additionally, there were 629 private health facilities, resulting in a healthcare coverage of 92%. There are close to one million internally displaced people in the region residing in 94 IDP centers.

Study design and period

We conducted a cross-section survey to verify starvation suspected deaths among individuals who have died since the Pretoria peace agreement from November 02, 2022, until July 30, 2023. Data were collected from August 15 to 29, 2023.

Study population

All households with deceased family members were eligible for inclusion in the study. This inclusive approach facilitated a comprehensive examination of mortality within the community, enabling a deeper understanding of the factors contributing to these losses.

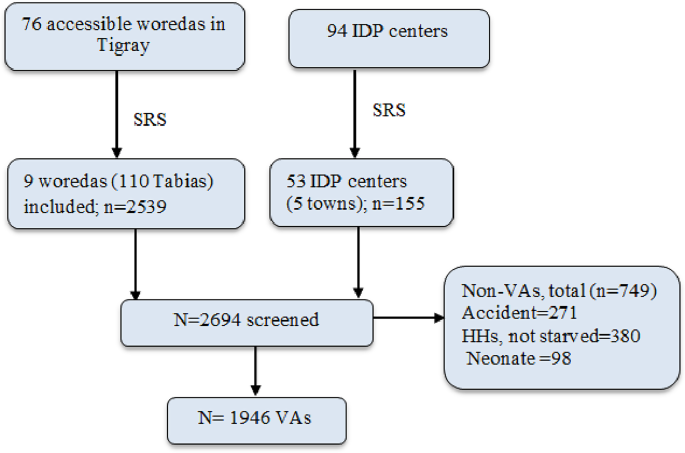

Sampling technique and sample size

Initially, we had the plan to assess and verify all causes of death from all accessible (76) districts of Tigray. However, due to budget constraints, we opted to randomly select nine districts. In the selected woreda, all Tabias were censused to trace for deaths of any cause in the community. Besides, we included 53 IDP centers in five big towns (Fig. 2). In each selected woreda, all causes of death were enrolled, screened, and verified accordingly. A total of 2694 deaths were identified from the study area.

Screening approach for cause of death

The screening for causes of death in the study employed a systematic approach involving households with deceased family members. Initially, all deaths were identified within each Tabia, the smallest administrative unit, and subsequently screened for perceived causes, with a particular emphasis on suspected starvation-related deaths using a screening tool (S1 cause of death screening tool, HHS and verbal autopsy questionnaire). This process included the application of a verbal autopsy questionnaire to validate suspected cases, enabling the collection of detailed information from caregivers regarding the circumstances surrounding each death. This methodology was similarly applied to confirm deaths attributed to starvation among internally displaced persons (IDPs) during the specified timeframe.

Data collection procedure

Fifty trained health professionals utilized the VA tool to conduct individual household visits to the families of deceased individuals. During these visits, they interviewed family members or close relatives and collected data electronically using smartphones. We collected primary data on socio-demographic information, feeding status and clinical data of the deceased, and hunger risk of household (HH). Data collection was made using face-to-face interviews with family members of the deceased. During the field investigation, we first met woreda health office/social affairs to record the number of deaths; then we interviewed family members of the deceased to screen the nutritional situation (food intake) of the deceased one month before death. We also conducted a verbal autopsy to verify starvation-related deaths among households with suspected ones. All households were also screened with a deceased for current hunger using a household hunger scale. For further clarity and trustworthiness of the data collected, GPS data were taken from each household.

Data collection tool

We utilized Verbal Autopsy (VA) Questionnaires adapted from guidelines for investigating suspected starvation deaths. This tool was developed by the Hunger Watch Group of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (JSA) and the Public Health Resource Network (PHRN) of India [26]. The adaptation of the questionnaire draws from WHO guidelines while integrating local knowledge and practices to enhance its applic uh ability and effectiveness in low-resource settings where formal medical records may not be available [26]. The questionnaire is not only scientifically robust but also more relevant to allow for accurate data collection regarding the circumstances surrounding starvation-related deaths.

The VA questionnaire had major sections such as (1) Personal identification details, (2) Family food supply-related information, and category-wise status of food items being consumed by the family, (3) Individual dietary history during the week and the month before death, (4) Unnatural food consumption patterns such as begging or borrowing food, consumption of unusual foods such as leaves of plants, forest tubers, (5) Signs and symptoms during the last illness, as well as any medical records and prescriptions, (6) Physical appearance at the time of death (S1 cause of death screening tool and verbal autopsy questionnaire).

Outcome ascertainment

We used the Physician-coded verbal autopsy (PCVA), which is the most widely used method which was mainly developed to offer information on the cause of death in communities where there was very limited access to healthcare and medical certification of causes of death [27, 28]. In such situations, the only viable source of information on the terminal illness is from caregivers of the deceased, most often the family members. Hence, the information collected on the symptoms suffered and signs observed was given individually and independently to a panel of physicians to ascertain the probable cause of death.

The panel of physicians employed verbal autopsies for all deaths occurring in individuals older than one month. To ascertain the probable cause of death, each verbal autopsy (VA) questionnaire was interpreted independently by a panel of three physicians who had prior experience with VA tools, thereby facilitating their effective participation in the study. The involvement of a panel helps mitigate individual biases and discrepancies that may arise when a single physician interprets the data. The physicians in the verbal autopsy assessment panel (who did not communicate with each other about their opinions) filled in a VA analysis table for their convenience, and then wrote their opinions on the probable immediate and underlying causes of death of the individual. The final opinion was arrived at based on the level of agreement among the three independent medical opinions. In case, all three of the doctors in the assessment panel opine that the underlying cause of death has been ‘Starvation’, then the final opinion states that the ‘most probable’ cause of death is attributable to ‘Starvation’.

The final opinion states ‘probable’ in case two of the three doctors agree on the nexus between starvation and subsequent death and possible if only one of the doctors in the panel mentions starvation as a probable cause of death. In case all three doctors opine that the disease or condition of death is not related to ‘Starvation’, the final opinion states that the cause of death is unrelated to ‘Starvation’.

Household hunger scale measures

The Household Hunger Scale (HHS) is a scientifically validated tool designed to measure household hunger, specifically targeting severe food insecurity [29]. It is derived from the broader Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) and utilizes the last three questions of the HFIAS (Q7, Q8, and Q9) to assign a score that reflects the level of hunger, ranging from no hunger to severe hunger. The selection of these questions is based on their consistent interpretation across various cultural contexts and their focus on severe food insecurity experiences, ensuring that responses accurately represent comparable levels of food deprivation [30]. A significant strength of the HHS lies in its validation for cross-cultural use, which facilitates meaningful comparisons across diverse populations and settings. This capability is crucial for identifying areas in need of resources and interventions, as well as for monitoring and evaluating food security policies and programs. Overall, the HHS effectively captures the severity of hunger in a manner that is both reliable and relevant across different sociocultural environments [29].

Thus, we used the three occurrence and three frequency questions to estimate the level of hunger in the households assessed (S1 cause of death screening tool, HHS and verbal autopsy questionnaire). The total scores in HHS range between zero and six. Households with 0–1, 2–3, and 4–6 scores were classified as having little or no hunger, moderate hunger, and severe hunger, respectively [29, 31]; then, the prevalence of household food with hunger was calculated after categorizing households into respective groups.

Operational definitions

Suspected starvation death

Any death where family members report that the deceased had significantly reduced food intake due to non-availability of food, during the month before death.

Starvation deaths

refer those deaths that have been identified as resulting from starvation or acute malnutrition, particularly in children under the age of fifteen.

Data quality management

An assessment tool was prepared by the research team and translated into Tigrigna, the local language. We trained health professionals for four days about the tool, study objective, method of data collection, and consent procedures. The research team closely supervised the data collection process. After the final editorial of the assessment tool, it was transferred into the ODK electronic questionnaire. Each questionnaire was checked visually for completeness and consistency daily. Data were collected using ODK/Smartphone. For further clarity of the data collected, the villages where data were collected were spotted by GPS. Every day raw data on the fieldwork was monitored and evaluated by the supervisors. All data were submitted daily and stored in the database. Data collection and physician interpretation of VA data were done simultaneously.

Data analysis

Stata version 16 was used for all analyses. Data were assessed for errors and missing values. Once the data was cleaned and processed, we made a descriptive analysis to determine the proportion of people who were suspected of starvation and were verified by the verbal autopsy. Frequency tables and percentages are used to give the results summary. To ascertain the possible association between a few important socio-demographic characteristics and the causes of death connected to hunger, a bivariate analysis was conducted. This involved using the independent T-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. We determined statistical significance at a p-value of < 0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

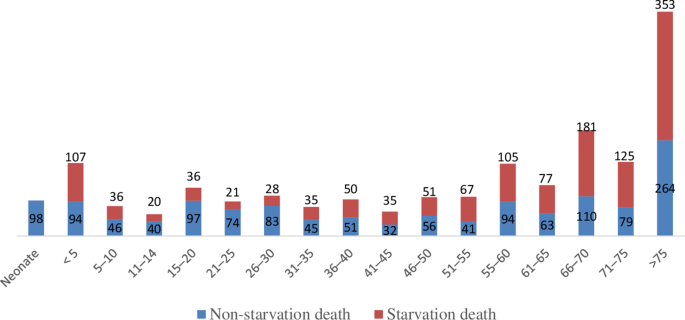

From November 2023 to July 2023, a total of 2694 deaths were registered by the nine districts of Tigray. From a total of 2694 deaths reported, 1946 (72.2%) verbal autopsies were performed, and 1875 (96.4%) of these were assigned the root cause of death. The total deaths that occurred in the neonatal period were 3.6%, n = 98. About 201 (7.5%) deaths occurred in under-five children. The highest deaths occurred during the age group of 76 and above (22.9%, n = 617). There were higher numbers of male than female deaths, with 1489 (55.3%) males and 1205 (44.7%) females.

There is a considerable variation in the number of deaths reported across the districts of Tigray. The highest proportions of deaths were reported in the rural districts of Hawzien 381 (14.1%) and Adwa 372 (13.8%). But the crude mortality rate was highest in D/Temben (1568 per 100,000) and lowest in L/Qoraro (228 per 100,000) (Table 1).

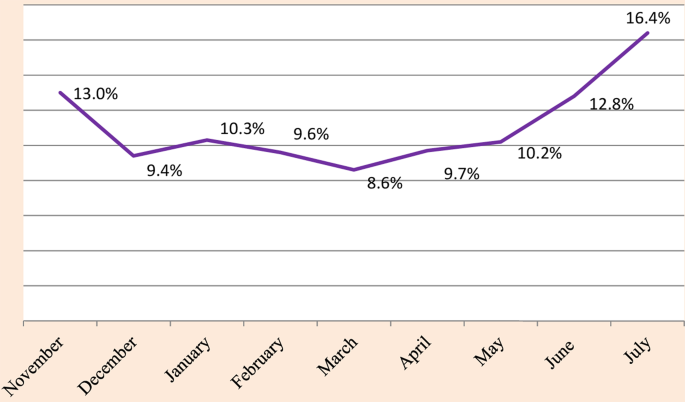

The monthly pattern of death is depicted in Fig. 3, revealing that nearly 50% of total deaths occurred during the last four months of the study period (April, May, June, and July). Although the temporal patterns of death before and after aid suspension did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference (independent t-test: p-value = 0.23, mean difference = -39.45), there was a notable increase in mortality from April to July, with the highest proportion of deaths reported in July at 16.4% (n = 307).Table 1 District variation of the deceased from November 2022 to June 2023, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia

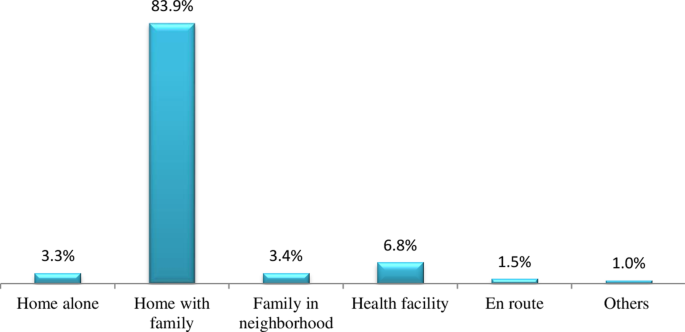

Place of death

More than nine out of ten deaths (90.6%) occurred at home. But the proportion of deaths at a health facility was only 6.8%, while En route, it was 1.5% (Fig. 4). In this study, the verbal autopsy system is shown to be an effective tool in this context, where the bulk of deaths take place outside of a medical facility and mortality data is limited.

Specific causes of death

From a total of 1946 deaths that were verbal autopsies performed, starvation was the predominant cause of death across all ages (68.3%, n = 1329). A total of 94 (72.3%) of the deceased people from the IDP centers and 1235 (68.0%) residents from the nine districts died of starvation. Thus, of a total of 2694 deaths reported in the study area, about 94/155 (60.3%) in IDP and 1235/2539 (48.6%) in the community were due to starvation. Next to starvation, other diseases such as infectious disease, single and multi-organ failure, and anemia were also reported as the highest causes of death in the study area. Higher starvation-related deaths occurred in under-five children, but it was the highest in the age group of 66 and above (Fig. 5).

By considering the 15–49 years old people as a reference category, the association of hunger death in children under five was found statistically significant (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.22–2.34). The association was also statistically significant in the age category of 50 and above years. Deaths due to starvation were more likely to occur in IDP (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.22–2.34) compared to at community level. Regarding sex, females aged 5 to 14 were more likely to die from hunger than males (p = 0.044) (Table 2).

A total of 16,342 deaths were estimated with a 95% CI of 15,718–16,987, when the total death is projected to reach 76 accessible woredas of Tigray with a total estimated population of 4,858,845 (projected from the 2015 census). Of all deaths, 7,949 were due to starvation, with a 95% CI of 7531–8411.

Table 2 Factors associated with hunger deaths in the study area

Specific cause of death by age group children

Table 3 summarizes the various causes of death among children in the study area. Approximately 201 deaths (7.5%) occurred in children under five years of age (1–59 months). Across all ages (children from 28 days to 15 years of age), the main causes of death were severe acute malnutrition (immediate cause: 12.6%; underlying cause: 83.8%). Those were followed by severe dehydration, hypovolemic shock, and multi-organ failure. From the total number of people whose verbal autopsies were performed, about 11.3% (male) and 15.3% (female) died of severe acute malnutrition during this age. Relatively, malaria (0.4%) was contributing to low death rates among children. About 51 (22.1%) of all deaths were classified as indeterminate.Table 3 Immediate and underlying causes of death among children

Adults

Table 4 presents the immediate and underlying causes of death among adults. From age 15 onwards, starvation was the most common underlying cause of death among adults (83.9%, n = 1046). At this age, people died of causes related to single and multi-organ failure as immediate causes (41.0%, n = 617), anemia, and hypoxia (6.9%, n = 104). Respiratory failure, pneumonia, and tuberculosis had a high contribution to the death of people in the study area. Relatively, malaria was also found to be a lower cause of death (0.4%, n = 6) among the study groups. About 40 (2.7%) and 31 (2.1%) of all deaths had indeterminate and not available causes of death, respectively.Table 4 Immediate and underlying causes of death among adults

Household hunger and food security conditions

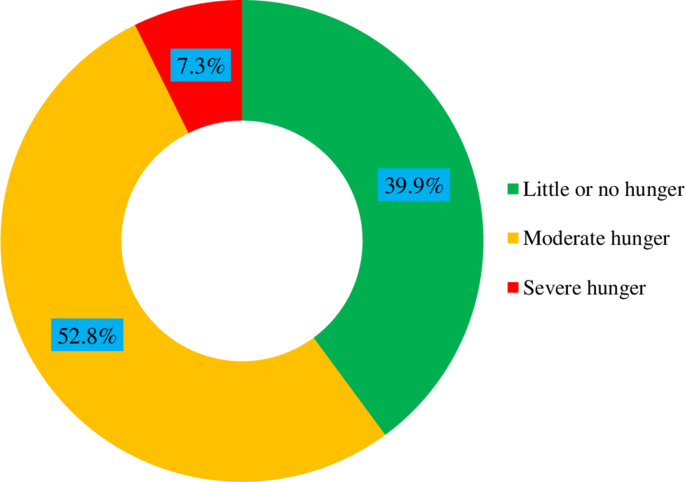

Analysis of the Household Hunger Scale (HHS) shows that large proportions of households (60.1%) had moderate or severe hunger. As illustrated in Fig. 6, based on responses to questions in the HHS, about 7.3% of households reported experiencing severe hunger, which is often having no food of any kind in the house. Members of households often go to sleep hungry because there is not enough food, and they often go without access to food for a whole day and night in the last 30 days preceding the survey.

Participants expressed that they continue their lives without eating all day long due to a lack of money and access to food. One month before the death, about 1797 (66.7%) of households or deceased people were often deprived of food, and 945 (35.1%) of households or deceased people often had to eat foods that they didn’t want to eat because of a lack of resources to meet their needs. Similarly, 1811 (67.2%) of the household or the deceased often have to eat fewer meals than normal in a day because there is not enough food. More than 60% of the respondents distress the sale of cattle, vessels (goods), and other belongings to obtain food. Similarly, 89.1% (1527) of the deceased were not taking sufficient food to satisfy their hunger. Nearly 25% (421) of the deceased had to eat unusual or ‘famine’ foods (such as roots, tubers, leaves, etc.) (Table 5).

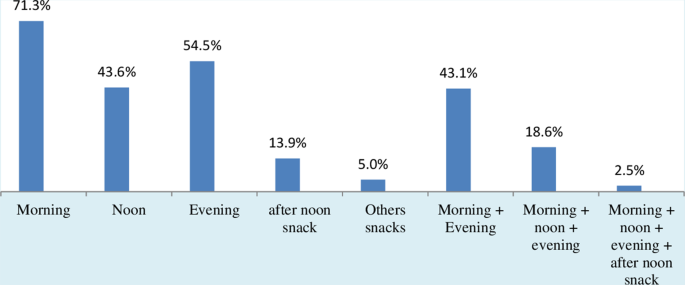

One month before death, only 71% (1222) of the deceased had the opportunity to eat in the morning. While about 56.3% (964) and 45.5% (780) of the deceased were not able to eat at noon and evening, respectively (Fig. 7).

Table 5 Information about contextual factors interrelated to deaths

Discussion

In this study, a verbal autopsy system was used to identify the causes of deaths among the study groups, after the periods of the Pretoria peace agreement between the government of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) [32]. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to estimate hunger-related deaths across the country.

Deaths from all causes recorded in the study areas was rising sharply after the aid suspension, almost doubling from 159 in March to 307 in July. The death rate among the study groups that we observed was high and crossed even the emergency threshold of two deaths per 10, 000 people per day [33], during November, May, June, and July. The high burden of deaths was similarly noted among young children in camps for internally displaced people in southern Somalia [34]. Although Somalia has the highest rate of starvation deaths by country in Africa and in the world, with a rate of 42.27 deaths per 100,000 people [35], the number of death due to hunger were higher in our study subjects. This higher rate of death is often attributed to the food insecurity caused by the northern Ethiopian wars in the country [36].

The patterns of mortality increased during May and June and reached the highest proportion of deaths during the month of July. This might be also explained that there has been a complete suspension of food aid by the United States and United Nations, since April 2023 [18, 19]. The prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) has surpassed the emergency threshold, indicating a critical situation that contributes to mortality rates [25]. According to a Smart survey [37], GAM levels exceeding 15% are indicative of a nutritional emergency, which aligns with the observed patterns of increased mortality during this period. Hence, hunger is continuing in its worst form, and death reports are mounting concerning hunger [18, 20, 21]. Thus, to address the severe food shortages and prevent further loss of life from starvation, the situation in Tigray highlights the urgent need for sustained international aid.

The place of death can be determined by human resource limitations, poor infrastructure, and insufficient equipment and supplies [38].The present study showed that more than 90% of deaths occurred at home, whereas the proportion of deaths that occurred in a health facility was only 6.8%. Similarly, higher numbers of deaths at home were reported from different countries of the world [39,40,41,42]; but the numbers of deaths at home were highest in our study. This is not surprising, given the lack of transport access and medical equipment, the insufficient number of health care providers, and the stock-out of drugs at the health facilities could result in the highest deaths of people at home. In this study, the war on Tigray was causing the wanton destruction of health facilities, with no medical equipment, no availability of drugs, and an insufficient number of health workers [25, 43]. However, more deaths at health facilities were reported from other parts of Ethiopia [44] and Angola [45].

Despite pledges from world leaders that famine will never occur again in the twenty-first century, the threat of famine is once again imminent in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. The second goal of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 2), established by UN Member States, aims to achieve zero hunger by 2030, specifically targeting food security and improved nutrition [46]. However, the current study reveals that starvation was the leading cause of death among both children and adults, accounting for 68.3% of total deaths. This alarming figure underscores the severe impact of food insecurity, which has been exacerbated by ongoing crises [47]. Our findings contrast with global trends where other causes dominate mortality statistics. For instance, tuberculosis and cerebrovascular diseases are reported as leading causes in other parts of Ethiopia [39], while diarrheal diseases and measles are prevalent in Somalia [34], In Gambia, acute respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases are significant contributors [42], and in Angola, communicable diseases and injuries are prominent [45]. In Bangladesh, circulatory system diseases, diarrhea, and malignancies rank among the top causes of death [48, 49].

Findings from a previous study conducted in Ethiopia [50], reported that the median age at death was at 70 years. However, in the current study, we found the highest deaths at both adult age and children. Deaths due to starvation were more likely to occur in children under five (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.22–2.34). This is due to the fact that poverty, susceptibility, and the global health challenge of malnutrition all have an impact on the burden of malnutrition on children from the poorest communities [51]. Although Dyson [52] reported a female survival advantage observed in famines, our findings indicate that females were more likely to die from hunger than males. Women frequently eat the least in war-torn nations, making sacrifices for their families; and overall gender inequality, which includes unequal treatment and practices creates women in a cycle of disadvantage and poverty making them more susceptible to hunger [53]. The prevalence of starvation-related deaths among internally displaced persons (IDPs) is significantly higher than in community settings, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.7 (95% CI: 1.22–2.34), indicating that IDPs are more likely to succumb to starvation. This phenomenon has been documented in various studies, including one from Eastern Chad [54], which highlights the exacerbating factors of stress, disease, and inaccessibility to food in these vulnerable populations. The displacement of populations introduces new health risks, including exposure to unfamiliar diseases and a deterioration in nutritional status [55].

Our findings revealed that more than 60% of the households suffered from moderate or severe hunger. The proportion of households with moderate or severe hunger was higher compared to the prewar (3.3%) and even during the war period (35.9%) [31], it increased above 24–50% points suggesting that things are getting worse than before and the severity of hunger increase after the cessation of hostilities in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. The majority of the households expressed concern that they might not have enough food and would not be able to eat their favorite dishes. In addition, families were forced to eat fewer food varieties, smaller meals, and foods they did not want to eat. It was also reported that unusual or ‘famine’ foods (such as roots, tubers, leaves, etc.) were being eaten by the households. It is important to highlight that these dietary changes not only increase the risk of undernutrition and underweight but can also contribute to micronutrient deficiencies, which have significant health impacts even in the absence of being underweight.

Quite a significant proportion of households passed the entire day and night without eating anything and had no food at all. Only 43.1% of the deceased people/household shad the opportunity to eat both breakfast and dinner during the day. By the same token, only18.6% were able to eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner. This finding is in contradiction to the goals of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development to end hunger, achieve food security, and improve nutrition [46]. The declarations issued by the UN specialized agencies state the universal right to food; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states the right to an adequate standard of living, which ensures health and well-being, including food [55]. Thus, urgent freed humanitarian access can be considered as a short-term remedy to get food access to the poor in need communities in Tigray, northern Ethiopia.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of this study include the use of experienced health workers as data collectors who were backed up by a strong supervision team. The use of digital data gathering using standard Smartphone/ODK for administering the verbal autopsy questionnaire helped to streamline and speed up the interviewing process. The use of a pre-tested questionnaire, which was adopted and designed from the WHO VA tool, was contextualized and translated into Tigrigna to assess starvation deaths. Interviews were also conducted in the subject’s home to reduce recall bias. Since, conducting interviews in a familiar and relevant location can help reduce recall bias by providing participants with contextual cues that enhance memory retrieval. Research indicates that environmental familiarity can facilitate more accurate recollections, as it helps participants connect their memories to specific experiences in that setting [56].

However, this study had the following limitations. First, it relied on respondents’ ability to accurately recall information about the deceased, which can introduce recall bias. Research indicates that the interval between death and the verbal autopsy (VA) interview significantly affects recall accuracy; longer intervals are associated with increased inaccuracies in reported causes of death [57]. Additionally, we acknowledge that the short duration of the study may not adequately account for seasonal variations in cause-specific mortality, which can be influenced by factors such as food production and vector-borne diseases.

Since the funeral ceremony is conducted in a religious area, church and mosque leaders were not communicated; thus, the total number of deaths might be underestimated. The census or complete enumeration survey method was not applied. We were not also able to verify whether the neonates died of hunger or not. Despite efforts to improve the quality of the data, including ongoing training for data collectors and reviewer physicians, supportive supervision, and bringing in ICT experts for daily database control, the validity of the cause of death determined using VA could be impacted by a variety of factors, including the timing of the interview, the interviewers’ skill, not being able to see the signs and symptoms of a deceased person by the interviewer prior to death [50, 58].

Conclusion and recommendations

The findings of this study confirm the total deaths of people in Tigray, Ethiopia, after the Pretoria peace agreement between the government of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). The findings of this study established starvation as the main cause of death in both the IDPs and the community, with statistically significant differences between the two settings. These differences may be attributed to exacerbating factors such as stress, disease, and inaccessibility to food, which disproportionately affect these vulnerable populations. The current household hunger rate in the study area was unacceptably high, suggesting more starvation deaths. Therefore, the study estimates the main causes of death and provides a more detailed picture of mortality in Tigray, northern Ethiopia, which can inform policy, response planning, and priority setting.

The findings reflect a serious humanitarian emergency. Continuous advocacy is expected from the government side to save people’s lives in Tigray. An expedited humanitarian response is warranted from aid agencies to prevent more deaths. Moreover, rehabilitation activities, including the return of the displaced communities to their original homes, should be strengthened to rescue those facing moderate to severe hunger.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- John MP. The Lethal Intersection Between Hunger and HIV/AIDS. International Food Aid Conference, Kansas City April 2007.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO., The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. 2023.

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the UN. The State of Food Insecurity in the World. 2014.

- Universal Declaration of Human, Rights GA. Res. 217, U.N. Doc. A/810, at 71. 1948.

- See generally Sohn. Generally Accepted International rules, 61 WASH. L Rnv 1073. 1986.

- Sabine W, Thomas H, Markus L, Jens M, Sandra S. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Transformative Change through Sustainable Development Goals? Politics and Governance. 2021; 9 (1).

- World Food Programme (WFP). A Global Food Crisis – 2023: Another year of extreme jeopardy for those struggling to feed their families. 2022.

- Warsame AFS, Checchi F. Drought, armed conflict and population mortality in Somalia, 2014–2018: a statistical analysis. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(4):e0001136.Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Julie D. March. Food security and conflict: harvesting resilience in the face of a global crisis 016 CDS23E 2023.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO., The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Building resilience for peace and food security, Rome, FAO. 2017.

- Demeuse R. Acting to Preserve the Humanitarian Space: What Role for the Allies and for NATO? NATO Parliamentary Assembly, Committee on Democracy and Security. 2022.

- Magdy S. Groups: both sides used starvation as tool in Yemen war, Associated, 1 September 2021.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Monitoring food security in food crisis countries with conflict situations. 2022.

- The New Humanitarian: Tigray’s long road to recovery. Apr 2023. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2023/04/20/tigrays-long-road-recovery. Accessed 6 Jun 2023.

- UN. Adopting Resolution 2417, Security Council strongly condemns starving of civilians, unlawfully denying Humanitarian Access as Warfare Tactics. Volume 24. United Nations; May 2018.

- Perret L. Operationalizing the humanitarian–development–peace Nexus: lessons learned from Colombia, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia and Turkey. Geneva: IOM; 2019.Google Scholar

- African Union: Cessation of Hostilities Agreement between the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the Tigray Peoples’ Liberation Front (TPLF). Nov, 2022. https://www.peaceau.org/en/article/cessation-of-hostilities-agreement-between-the-government-of-the-federal-democratic-republic-of-ethiopia-and-the-tigray-peoples-liberation-front-tplf. Accessed 6 Jun 2023.

- Ben Farmer June. ‘At least 700’ people die from starvation in Ethiopia following food aid suspension 2023. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/climate-and-people/ethiopia-aid-starvation-deaths-tigray-food-aid-un/. Accessed 10 Aug 2023.

- USAID: Pause of U.S. Food Aid in Tigray, Ethiopia. 2023. https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/may-03-2023-pause-us-food-aid-tigray-ethiopia. Accessed 12 Jul 2023.

- Mihret GK, News. Hunger related death rises in Tigray amidst ongoing investigation into food aid diversion, persistent aid suspension, May 2023.

- Dawit E. Hunger haunts Ethiopia’s Tigray region after years of war | Reuters, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/hunger-haunts-ethiopias-tigray-region-after-years-war-2023-07-10/. Accessed 10 Jun 2023.

- Rédaction Africa news with AP. Hunger kills hundreds after US and UN pause food aid to Ethiopia’s Tigray region, officials say 2023, http://www.africanews.com/amp/2023/06/27/hunger-kills-hundreds-after-us-and-un-pause-food-aid-to-ethiopias-tigray-region-officials. Accessed 15 Jun 2023.

- Ethiopia-Global Hunger Index https://www.globalhungerindex.org/ethiopia.html. Accessed 18 Jun 2023.

- Food insecurity. Maternal, Infant, Young Child Feeding (MIYCF) Practices, and nutritional status assessment in Tigray, northern Ethiopia: Post-war scenario. 2023.

- Afework M, Mulugeta G. Saving children from man-made acute malnutrition in Tigray, Ethiopia: a call to action. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(2):e197–e198.

- Prasad V. Guidelines for Investigating Suspected Starvation Deaths. 2003. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313571351_Guidelines_for_Investigating_Suspected_Starvation_Deaths. Accessed 10 Jul 2023.

- Lozano R, Lopez AD, Atkinson C, Naghavi M, Flaxman A, Murray C. Performance of physician-certified verbal autopsies: multisite validation study using clinical diagnostic gold standards. Popul Health Metrics. 2011;9:32.Article Google Scholar

- Verbal autopsy standards: verbal autopsy field interviewer manual for the 2022 WHO verbal autopsy instrument; Geneva; World Health Organization. 2017; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Ballard T, Deitchler M, Ballard T. Household hunger scale: Indicator definition and measurement guide household hunger scale: Indicator definition and measurement guide. Washington, D.C.: FANTA-III; 2011.Google Scholar

- Deitchler M, Ballard T, Swindale A, Coates J. Introducing a simple measure of Household Hunger for Cross-cultural Use. Washington, D.C.: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance II Project, AED.; 2011.Google Scholar

- Aregawi W, Haftom T, Hiluf E, Meron M, Tsegay B, Rieye E, et al. Armed conflict and household food insecurity: evidence from war-torn Tigray, Ethiopia. Confl Health. 2023;17:22.Article Google Scholar

- Agreement for lasting. peace through a permanent cessation of hostilities between the government of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia and the Tigray people’s liberation front (TPLF), Pretoria, the Republic of South Africa, November 2, 2022.

- Checchi F, Roberts L. September,. Interpreting and using mortality data in humanitarian emergencies: a primer for non-epidemiologists. 2005. https://odihpn.org/resources/interpreting-and-using-mortality-data-in-humanitarian-emergencies. Accessed 10 Sep 2023.

- Seal JA, Jelle M, Grijalva-Eternod SC, Mohamed H, Ali R, Fottrell E. Use of verbal autopsy for establishing causes of child mortality in camps for internally displaced people in Mogadishu, Somalia: a population-based, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e1286–95.Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Starvation Deaths by Country. 2023. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/starvation-deaths-by-country. Accessed 18 Sep 2023.

- Araya T, Lee SK. Conflict and households’ acute food insecurity: evidences from the ongoing war in Tigrai-Northern Ethiopia. Cogent Public Health. 2024;11(1).

- Tigray Region. Ethiopia: SMART Survey Pooled Report. Bureau of Health, UNICEF Ethiopia. Retrieved from UNICEF Ethiopia; 2023.

- Canavan ME, Brault MA, Tatek D, Burssa D, Teshome A, Linnander E, et al. Maternal and neonatal services in Ethiopia: measuring and improving quality. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:473–7.Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Yigzaw K, Gashaw A, Abebaw G, Tadesse A, Mezgebu Y, Solomon M, et al. Tuberculosis and HIV are the leading causes of adult death in northwest Ethiopia: evidence from verbal autopsy data of Dabat health and demographic surveillance system, 2007–2013. Popul Health Metr. 2017;15:27.Article Google Scholar

- Gupta N, Hirschhorn LR, Rwabukwisi FC, Drobac P, Sayinzoga F, Mugeni C et al. Causes of death and predictors of childhood mortality in Rwanda: a matched case-control study using verbal social autopsy. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18(1).

- Manortey S, Carey A, Ansong D, Harvey R, Good B, Boaheng J et al. Verbal autopsy: analysis of the common causes of childhood death in the Barekese sub-district of Ghana. J. Public Health Afr. 2011; 2(2).

- Wutor BM, Osei I, Babila Galega L, Ezeani E, Adefila W, Hossain I, et al. Verbal autopsy analysis of childhood deaths in rural Gambia. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(7):e0277377.Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Gebretsadkan G, Mahlet A, Tedros B, Ferehiwot H, Freweini G, Tigist H, et al. Prevalence and multi -level factors associated with acute malnutrition among children aged 6–59 months from war affected communities of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, 2021: a cross -sectional study. Confl Health. 2023;17:10.Article Google Scholar

- Tesfay N, Tariku R, Zenebe A, Habtetsion M, Woldeyohannes F. Place of death and associated factors among reviewed maternal deaths in Ethiopia: a generalised structural equation modelling. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e060933.Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Rosário VNE, Costa D, Timóteo L, Rodrigues AA, Varanda J, Nery VS, et al. Main causes of death in Dande, Angola: results from Verbal autopsies of deaths occurring during 2009–2012. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:719.Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- United Nations. The sustainable development goals report 2020. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2020.

- Seal A, Checchi F, Balfour N, Haji Nur A, Jelle M. A weak health response is increasing the risk of excess mortality as food crisis worsens in Somalia. Confl Health 11;12:(2017).

- Baqui AH, Black RE, Arifeen SE, Hill K, Mitra SN, Sabir A. Causes of childhood deaths in Bangladesh: results of a nationwide verbal autopsy study. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(2).

- Nahar Q, Alam A, Mahmud K, Sathi SS, Chakraborty N, Siddique AB, et al. Levels and trends in mortality and causes of death among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: findings from three national surveys. J Glob Health. 2023;25:13.Google Scholar

- Melaku YA, Sahle BW, Tesfay FH, Bezabih AM, Aregay A, Abera FS, et al. Causes of death among adults in Northern Ethiopia: evidence from Verbal Autopsy Data in Health and demographic Surveillance System. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e106781.Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Malnutrition. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition. Accessed 20 Sep 2023.

- Dyson T. On the demography of south Asian famines: part I. Popul Stud. 1991;45(1):5–25.Article Google Scholar

- Gender Inequality, women are hungrier. 2023. https://www.wfpusa.org/drivers-of-hunger/gender-inequality/. Accessed 15 Sep 2023.

- Guerrier G, Zounoun M, Delarosa O, Defourny I, Lacharite M, Brown V, et al. Malnutrition and mortality patterns among internally displaced and non-displaced population living in a camp, a village or a town in Eastern Chad. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e8077.Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Seaman J. Famine mortality in Africa. IDS Bull. 1993;24(4):27.Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Smith J, Doe A. The role of Environmental Context in Memory Recall: implications for Research Methodology. J Cogn Psychol. 2023;45(2):123.Google Scholar

- Hernandez A, Morrow R, O’Rourke K. The impact of recall bias on verbal autopsy data: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22(1):130.Google Scholar

- Fottrell E, Byass P. Verbal autopsy: methods in transition. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32:70–81.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Tigray Health Bureau and Tigray Health Research Institute for their overall activities and support during the data collection. We would like to thank the data collectors and Physicians. The support from the woreda administrators, study participants, and health extension workers is dully acknowledged.

Funding

The study didn’t receive any specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Tigray Health Research Institute, Tigray, EthiopiaMekonnen Haileselassie, Hayelom Kahsay, Tesfay Teklemariam, Ataklti Gebretsadik, Ataklti Gessesse, Abraham Aregay Desta, Haftamu Kebede, Nega Mamo & Degnesh Negash

- Tigray Regional Health Bureau, Tigray, EthiopiaMengish Bahresilassie, Rieye Esayas & Amanuel Haile

- School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Mekelle University, Tigray, EthiopiaGebremedhin Gebreegziabiher, Amaha Kahsay, Gebremedhin Berhe Gebregergs, Hagos Amare & Afework Mulugeta

Contributions

AM, HK, AH, MH, GBG, HA, TT, RE, and AK conceptualized and designed the study. MH, GBG, HA, TT, AG, AG, GG, NM, DN, HK, AAD, and AK participated in supervision and fieldwork. MH, GBG, HA, and TT made significant contribution to data management and analysis. MH drafted the manuscript. AM, HK, AH, MH, GBG, HA, TT, and MB critically reviewed the first draft of the manuscript and contributed to further development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mekonnen Haileselassie.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participation

Ethical clearance was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Tigray Health Research Institute (Reference number: THRI/4031/0379/16) and a support letter was obtained from Tigray Regional Health Bureau. Oral informed consent was obtained from each subject after the purpose and nature of the study were explained to each study participant. Privacy of the study participants was strictly protected throughout the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Cite this article

Haileselassie, M., Kahsay, H., Teklemariam, T. et al. Starvation remains the leading cause of death in Tigray, northern Ethiopia, after the Pretoria deal: a call for expedited action. BMC Public Health 24, 3413 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20932-9

- Received10 January 2024

- Accepted02 December 2024

- Published18 December 2024

- DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20932-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:Get shareable link

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Keywords

- Sections

- Figures

- References

- Abstract

- Background

- Methods and materials

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion and recommendations

- Data availability

- References

- Acknowledgements

- Funding

- Author information

- Ethics declarations

- Additional information

- Electronic supplementary material

- Rights and permissions

- About this article

Advertisement

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

Contact us

- General enquiries: journalsubmissions@springernature.com

- Read more on our blogs

- Receive BMC newsletters

- Manage article alerts

- Language editing for authors

- Scientific editing for authors

Follow BMC

By using this website, you agree to our Terms and Conditions, Your US state privacy rights, Privacy statement and Cookies policy. Your privacy choices/Manage cookies we use in the preference centre.

© 2024 BioMed Central Ltd unless otherwise stated. Part of Springer Nature.chrome-extension://iplffkdpngmdjhlpjmppncnlhomiipha/unpaywall.html