An edited extract from: Unbroken Chains: A 5,000 year history of African Enslavement, published 28 August 2025.

In the global reckoning with slavery, Ethiopia occupies an ambiguous space. Often romanticized as the lone African polity to successfully resist European colonization and celebrated in the pan-African imagination as a beacon of Black sovereignty, Ethiopia has long been cloaked in an aura of moral immunity. Nowhere is this mythology more evident than in the figure of Emperor Haile Selassie I, the so-called “Lion of Judah,” who remains a revered symbol in the African diaspora.

Yet, behind the regal image and resistance lies a less celebrated history—one in which Ethiopia was not only complicit in, but also deeply enmeshed with, the long and brutal history of African enslavement.

A Legacy of Enslavement Before Selassie

The enslavement of Africans within Ethiopia stretches back centuries. Long before European ships docked on Africa’s shores, highland Ethiopia had developed its own internal and external slave systems.

Richard Pankhurst, among the most eminent of historians of Ethiopia, provided this assessment.

Warfare, which in the Ethiopian region dates back to the dawn of history, led to the capture of slaves of many ethnic groups. A significant proportion of the men, women and children thus seized were taken, however, from the less powerful communities of the periphery of the state, notably from what is now the borderlands of the Sudan, from peoples who, being in many cases culturally distinct, were regarded as morally easier to enslave than other inhabitants of the area.

Enslavement was driven by war, raiding, tribute, and conquest—particularly targeting lowland and peripheral populations such as the Oromo, Sidama, and Shankilla peoples. These groups were often deemed “pagan” or “barbarian” by the Orthodox Christian ruling elite and therefore justifiable targets for servitude.

Slaves served in a variety of roles: domestic servants, agricultural labourers, artisans, concubines, and soldiers. Ethiopian rulers built their courts and military apparatuses in part on the backs of the enslaved. While some slaves could rise to influential positions—particularly those integrated into the royal household—the system was brutal and stratified.

Slaves were an integral part of the trade with Arabia and Egypt. By the reign of Emperor Lalibela (ca. 1181 -1221) Ethiopia had trade links with both Egypt and Aden. The commerce in slaves was controlled by Muslims along the coast of the Horn, with Arabs taking most of the profits. Slaves were also taken by dhow up the Red Sea to satisfy the Egyptian demand for Ethiopians who were used as soldiers. As Harold Marcus explains: ‘In return, Cairene and Alexandrian merchants shipped textiles and finished goods to the port of Mitsawa,’ (in present day Eritrea) ‘by then Ethiopia’s most important emporium.’ During the succeeding centuries the trade fluctuated with the fortunes of Ethiopia’s emperors.

Haile Selassie: The Contradictions of a Modernizing Monarch

Haile Selassie, who reigned (with a brief interruption during the Italian occupation) from 1930 to 1974, is often portrayed as a modernizing monarch who guided Ethiopia into the 20th century. A key figure at the League of Nations, a voice against fascist aggression, and a symbol for the Rastafarian movement, Selassie projected a vision of enlightened African leadership. However, beneath the surface of these international accolades lay a troubling domestic reality.

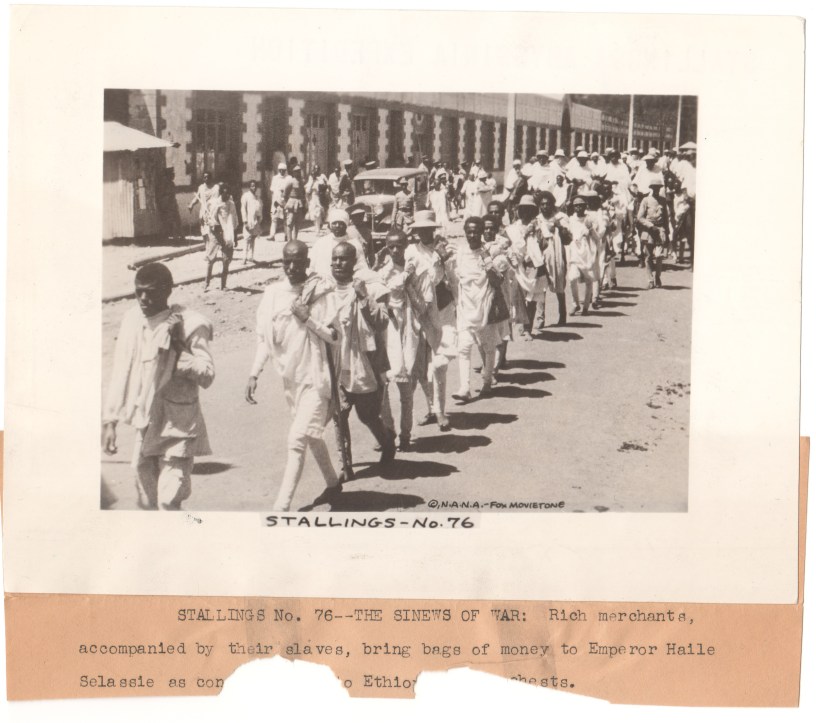

Slavery persisted in Ethiopia well into the 20th century—long after it had been legally abolished in most of the world. When Haile Selassie assumed power, slavery was still legally sanctioned and practiced widely, particularly in rural regions where central authority was weak. Tens of thousands of Ethiopians remained in bondage—some estimates put the number as high as 400,000 in the early 1930s.

Selassie’s relationship to slavery was deeply ambivalent. On the one hand, he understood the need to present Ethiopia as a modern, civilized state to the international community. On the other, he depended on the feudal nobility—many of whom were slaveholders—for political support. His reforms were thus cautious and calculated.

In 1923, under pressure from the League of Nations, Ethiopia formally outlawed the slave trade. Yet this was largely a symbolic gesture. Slavery itself remained legal until 1942, and even then, enforcement was spotty at best. The emperor issued edicts condemning slavery and establishing commissions to oversee manumission, but these often lacked teeth. Reports from foreign diplomats and journalists throughout the 1930s and 1940s describe ongoing enslavement in the provinces, forced labour masquerading as tax, and widespread resistance from landowning elites to any attempts at emancipation.

Haile Selassie himself owned slaves early in his career and they worked on his royal estates. While the emperor legislated, and spoke out against the practice, his own family continued to benefit from it. Some 600 slaves were sent to Haile Selassie’s wife as late as 1927. His reluctance to confront slavery head-on allowed the institution to linger longer in Ethiopia than in almost any other part of Africa. His balancing act—appeasing foreign allies while preserving the loyalty of internal power brokers—meant that genuine abolition was more rhetorical than real for much of his reign.

Slow Reform

The experience of slavery remains deeply ingrained in Ethiopia. The Gumuz suffered slavery until the second half of the twentieth century, well into the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie and possibly even longer. John Young recalls Gumuz explaining to him that ‘Oromos were taking slaves until 1993 and that students had to carry weapons to school to defend themselves,’ to prevent the children from being captured and enslaved. Gumuz elders continue to relate the deprivation they suffered well beyond this; describing the confiscation of their property, their eviction from their lands and their enslavement.

They are by no means the only ethnic group with these memories. Ethiopians alive today recall the slaves they knew in their childhoods. Parents would ask for a fair-skinned Oromo slave and a darker-skinned slave from the border region with Sudan when they were asked for their daughter’s hand in marriage. Slaves were regularly beaten in public to show a master’s ability to rule. Abductions and shackling were normal, and if babies cried when their mothers were seized, they were killed.

Myth and Memory

The persistence of slavery in Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia challenges the simplistic narrative of a morally untainted African monarchy. While Ethiopia avoided the formal colonization that befell much of the continent, it did not escape the internal hierarchies, exploitation, and racialized labour systems that characterized empires. It reproduced many of those same structures.

Selassie’s reluctance to address slavery decisively reflects a broader tension in African postcolonial leadership: the gap between the symbolic role of liberator and the practical obligations of maintaining power in deeply hierarchical societies. In this respect, Selassie was hardly unique. But his global reputation—as a moral exemplar and father of African unity—makes the dissonance particularly stark.

On 5 November 2021, during the war launched by Ethiopia and Eritrea against Tigray, an alliance was formed between the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front and eight other ethnic groups. In a live feed from the National Press Club in Washington, where the alliance was signed, the Oromo representative complained bitterly: ‘I have been treated like a slave all of my life.’ The wounds of enslavement in Ethiopia run deep and have not been expunged.

Today, discussions of slavery in Ethiopia remain muted. The subject is underrepresented in textbooks, rarely discussed in public forums, and often dismissed as a colonial smear. Yet without acknowledging this past, the country cannot fully reckon with the enduring inequalities rooted in that history.

Conclusion

Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia was a paradox: a nation that symbolized African freedom while perpetuating African enslavement. While the emperor’s diplomatic legacy is secure, his domestic record demands re-examination. To confront Ethiopia’s role in the history of African slavery is not to diminish its achievements, but to deepen our understanding of a continent shaped as much by internal contradictions as by external coercion.

its plain Truth that Haile Silasie and old Monarchy has done slavery as a meanse of their rule.

itd absolutely true story more can be written as it’s very important points to solve today’s problems in the Ethiopian Epire most of the conflicts are symptom of the problems but the root cause lies in worst history

many thanks for this dig out go a head for with evidence like reacharf Pankhurst professor demand claler many moreneutrals.