“Unbroken Chains”, which will be published on 28 August, radically expands the scope of how slavery in Africa is understood, moving beyond the widely known trans-Atlantic trade to emphasize a far older, wider, and more complex history.

While the Atlantic slave trade is etched into public memory, this is only a fragment of a story that stretches back over 5,000 years and continues today. Slavery in Africa involved not just Europeans but Arab, Indian, Ottoman, and African actors themselves.

A Global System of Enslavement

Slavery has been practiced throughout history, across all continents. Africa, however, has endured an especially extensive and enduring system. From 650 to 1900, over 41 million Africans were enslaved via different trade routes: across the Sahara, Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic.

If modern slavery is included, the number may approach 50 million.

The Portuguese were the largest European slave traders, transporting nearly 5.9 million Africans—mostly to Brazil. Britain followed, carrying over 3.2 million Africans primarily to the Caribbean and North America.

Africans were not just victims. Many African elites captured and sold slaves, often in exchange for goods such as textiles, alcohol, firearms, and horses. African rulers facilitated much of the trade by marching captives to the coast. European involvement was typically limited to coastal enclaves until the colonial scramble for Africa in the late 19th century.

Britain and the Atlantic Slave Trade

Britain was deeply involved in slavery from the 17th to the early 19th century. British ships, primarily from Liverpool, London, and Bristol, operated within the so-called “triangular trade”: British goods were traded for African slaves, who were transported to the Americas, with slave-produced goods like sugar and tobacco returned to Europe. The economic gains from this trade were vast, enriching merchants and helping to finance Britain’s industrial revolution.

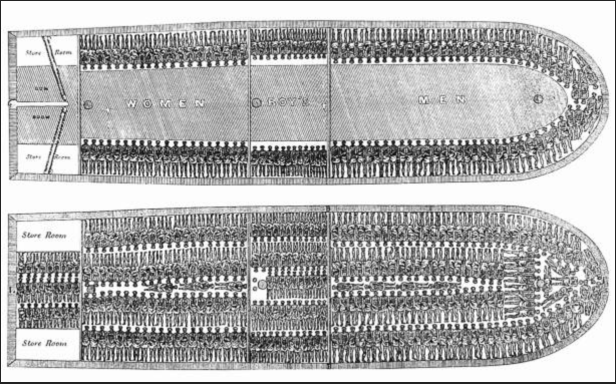

The British developed a sophisticated system to sustain the trade. The Royal African Company (founded 1660) was central to Britain’s early operations. British slave ships were notoriously brutal. Human cargo was packed into holds barely large enough to sit up in.

Fed meagre rations and confined for weeks, slaves were chained, disease-ridden, and subject to shocking mortality rates. Nearly 15% of those embarked died before reaching the Americas. Fear of insurrection led to violent discipline, and slaves who revolted were often tortured or killed. Britain’s role extended to brutal plantation regimes in the Caribbean, where sugar production relied on this coerced labour.

Resistance, Abolition, and the Royal Navy

Britain’s turn from slave trader to abolitionist power is one of the most dramatic shifts in this history. From the late 18th century, religious and moral campaigners, especially Quakers and Evangelicals, mobilized against slavery. Cases like the Zong massacre—in which 131 slaves were thrown overboard so their owners could claim insurance—galvanized public outrage.

Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act in 1807, banning British participation in the international trade. But the struggle to end slavery altogether continued. Slavery was not abolished in British colonies until the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which freed over 800,000 enslaved people in the Caribbean, South Africa, and Canada.

Britain then undertook an unprecedented global campaign to suppress the slave trade. The Royal Navy played a central role, deploying anti-slavery patrols across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Operating from bases in Cape Town and Mauritius, British ships captured hundreds of slave vessels. In 1872 alone, over 15,000 slaves passed through the Zanzibar customs house—evidence of the trade’s resilience.

Despite limited resources and resistance from Arab and Portuguese slavers, Britain signed treaties with regional powers, including the Sultan of Zanzibar, eventually compelling them to outlaw slave exports. The Royal Navy sustained these operations at great cost—up to 2% of national income for decades and the lives of thousands of British sailors. The last recorded interception of a slave dhow was in 1922.

Portuguese slavery in Angola and Mozambique

Portugal’s role in African slavery was older, deeper, and longer lasting than Britain’s. Portuguese explorers began trafficking enslaved Africans in the 15th century and continued the trade until the late 19th century. Their involvement was most concentrated in two colonies: Angola and Mozambique.

In Angola, the Portuguese transformed local societies through an enduring and violent system of slave raiding and trade. They first established a foothold in the region in the 1570s, founding Luanda in 1576. Angola became the principal source of slaves for Brazil, and by the 17th century, over 1.3 million people had been trafficked across the Atlantic from this region. The Imbangala, ruthless bands of warriors in central Angola, collaborated with the Portuguese to raid and enslave vast numbers of people.

These groups were incorporated into the colonial slave supply system, enriching both African rulers and Portuguese colonists.

Further inland, Portugal created a militarized system of conquest and trade. The Kwanza River served as an entry point into the interior, and new alliances with local groups—such as the kingdoms of Kasanje and Matamba—allowed the Portuguese to reach deep into the continent. The constant demand for slaves in Brazil, especially after the discovery of gold and the expansion of sugar and coffee plantations, sustained this trade. The profitability was enormous, with some Portuguese merchants achieving returns of up to 1,000%.

Mozambique also became a vital node in Portugal’s slave network. Although not as heavily trafficked as Angola, it served two key purposes: as a source of slaves for export to the Indian Ocean world and as a stepping stone for Portuguese ambitions in Asia. From the 16th to the 19th century, slaves were shipped from Mozambique to Brazil, India, the Mascarenes, and Southeast Asia. The Zambezi Valley was the heart of this trade. Portuguese settlers, known as prazeros, established estates (prazos) in the valley, run by private slave armies called achikunda. These armies conducted raids, enslaved thousands, and formed the backbone of colonial power in the region.

Portugal’s reach from Mozambique extended into South Asia and the Far East. Enslaved Mozambicans were taken to Goa, Macau, and even Japan. In return, Indian cloth and arms were traded in Mozambique. Gujarati merchants also played a vital role in financing and staffing Portuguese and Arab slaving operations, particularly in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Indian ownership of land and slaves on Zanzibar and Pemba was extensive.

Even after abolition, Portugal continued profiting from slavery, often turning a blind eye to illicit trafficking. When Brazil officially outlawed slavery in 1888, the focus of Portuguese slaving shifted back to supplying French plantations on Réunion and Mauritius. The colonial economy of Mozambique remained deeply embedded in coercive labour systems until well into the 20th century.

The Broader Impact

Britain and Portugal’s legacies in African slavery are profound. Both powers fuelled internal wars by trading guns for slaves and supported elites who enslaved rivals and civilians. The slave trade reshaped African politics, economics, and military systems, creating instability and warlordism. Dahomey, for example, militarized its society and imported over 100,000 muskets annually from Birmingham. In Angola, Imbangala warbands became mercenaries in service of European needs. In Mozambique, militarized estates ruled large swaths of land.

The subsequent abolition efforts—however laudable—did not erase centuries of suffering or undo the profound social transformations slavery had wrought. Even today, in countries like Saudi Arabia and Oman, the legacy of slavery continues in discriminatory attitudes toward Africans and ongoing labour exploitation.

Conclusion

Slavery in Africa was far more complex and far-reaching than commonly assumed. It involved not only Europeans but also Arab, Indian, Ottoman, and African actors across thousands of years. Britain and Portugal were central to the trans-continental slave trades, but also to their suppression. Their interventions—first as exploiters, then as self-declared liberators—left deep scars. This history challenges simplistic narratives and demands a more inclusive, more honest engagement with the global and African dimensions of slavery.