Austerity measures hailed abroad are leaving Ethiopians hungry at home. – Eyob Yohannes

Ethiopia Insight, Oct 08, 2025

On paper, Ethiopia’s debt service looks “manageable.” In its July 2025 review, the IMF praised government reforms as “progress” and unlocked $262.3 million in new financing. In London and New York, bondholders debate haircuts and sustainability ratios, dismissing Ethiopia’s request for a modest 20% cut to its $1 billion Eurobond as excessive.

But in Ethiopia, progress tastes bitter: it translates into bread that costs twice as much, a fuel tank left half-empty, and a medicine shelf stripped bare. It is the silence of a parent calculating which child will eat more today, and which tomorrow.

Ethiopia’s debt had already swelled from $13.7 billion in 2011 to $54.7 billion by 2020, an economic weight and a political liability that reforms now struggle to contain.

Bitter Progress

In June 2025, the government scrapped the fuel subsidy under IMF pressure to ‘rationalize’ prices. Officials called it necessary; citizens called it cruel. Taxi fares soared, and food costs climbed with every kilometer of transport.

Observers pointed out that scrapping fuel and electricity subsidies—together with the birr’s devaluation—pushed the population to the brink.”

In July 2024, Ethiopia floated the birr, another IMF condition. Exporters may cheer, but for families it meant doubled costs for wheat, fertilizer, and school supplies. A mother hears ‘market-determined exchange rate’ and wonders why her child’s antibiotic is suddenly out of reach.

As analysts observed, the float may restore efficiency, but it leaves households drowning in price volatility and diminished purchasing power.

Yes, the IMF sets the conditions. Yes, bondholders refuse compromise. But Ethiopia’s government is not innocent. It borrowed recklessly, building prestige projects while exports stagnated. It rationed foreign exchange through favoritism, rewarding insiders and starving small businesses. It kept subsidies as political shields, then tore them away in one stroke when creditors pressed.

The suffering today is not only imposed from abroad. It is also the deferred bill for choices made at home.

Perilous Timing

Reforms arrive in a fractured country. In Amhara, anger over the April 2023 dismantling of regional special forces erupted into conflict. In Oromia, insurgency grinds on. Add fuel hikes, bread shortages, and soaring transport costs, and pain multiplies. Old grievances harden, leaving ordinary Ethiopians trapped between government decrees, rebel checkpoints, and a market that delivers less each day.

Analysts argue that pushing reforms in the midst of unresolved conflicts only compounds instability and hardship.

There is logic beneath the pain, though. If carried through, reforms could tame inflation, attract investment, and give Ethiopia breathing space. The G20 Common Framework already promises $2.5 billion in debt-service relief through 2028.

But that hope will vanish unless the government admits the truth: that citizens are paying for its mistakes. Unless it builds safety nets that actually reach households. Unless it proves that sacrifice today leads to relief tomorrow.

Support Ethiopia Insight on Patreon

Hard Truths

The IMF cannot measure success only in ratios. Bondholders cannot demand repayment from a country running on hunger. And the Ethiopian government cannot hide behind technical jargon while its citizens tighten belts past the last notch.

Debt reform is not just about creditors abroad. It is about trust at home. A father should not have to choose between bus fare and dinner. A mother should not have to skip medicine for herself so her child can eat.

Until those lives are acknowledged, Ethiopia’s reform will not be progress. It will be despair dressed as policy.

Ethiopia’s reforms are not merely technical tweaks; they are political choices with winners and losers. If the state keeps socializing debt costs onto households while shielding elites and creditors, resentment will deepen.

A sustainable path demands not just debt relief, but a political settlement that places citizens—not spreadsheets—at the center. Without it, Ethiopia risks trading financial solvency for social collapse.

About the author.

Eyob is a writer and data analyst based in Ethiopia. His work explores the intersection of political power, identity, and economic dependency in contemporary African states.

While the article raises important moral concerns about the social impacts of economic reform in Ethiopia, its framing is unduly pessimistic and dismissive of the broader complexities involved in managing national debt and economic recovery.

The tone, though emotive, borders on sensationalism and overlooks key economic and political dynamics that deserve more balanced consideration.

First, reforming a debt-laden economy requires both technical rigor and social sensitivity. It is not a binary choice between ratios and people it must be both. The IMF’s involvement and focus on fiscal metrics, while imperfect, are not inherently dehumanizing. These tools exist to ensure macroeconomic stability, without which sustained social progress becomes impossible. To suggest that bondholders or creditors are blind to human cost is to ignore the nuanced global discourse around debt restructuring, especially in low-income countries.

Second, the piece unfairly paints the Ethiopian government as a monolith hiding behind “technical jargon.” This oversimplifies the political economy of reform and ignores the efforts of many within the country who are working to balance fiscal discipline with social protection. Ethiopia’s leadership like many others navigating economic crisis is caught between competing pressures: meeting creditor expectations to regain access to capital markets, and responding to immediate domestic needs with limited resources.The article also fails to recognize that not all reform outcomes are regressive. Yes, there are winners and losers in economic transitions, but the long-term objective is to create a more sustainable, inclusive economy. Highlighting the sacrifices of everyday Ethiopians is important, but doing so without acknowledging the broader necessity of reform risks romanticizing the status quo, which itself has failed to deliver prosperity for many.

Lastly, the call for a “political settlement that places citizens—not spreadsheets—at the center” is valid, but it should not come at the cost of rejecting the hard economic truths that countries like Ethiopia must face. Constructive reform must be both technically sound and socially just. Rather than deepening cynicism, the focus should be on how to strengthen transparency, accountability, and citizen participation in the reform process.In short, Ethiopia’s path forward must be one of balance—not despair versus policy, but integrated solutions that value both fiscal sustainability and human dignity. That is a far more productive and empowering narrative.

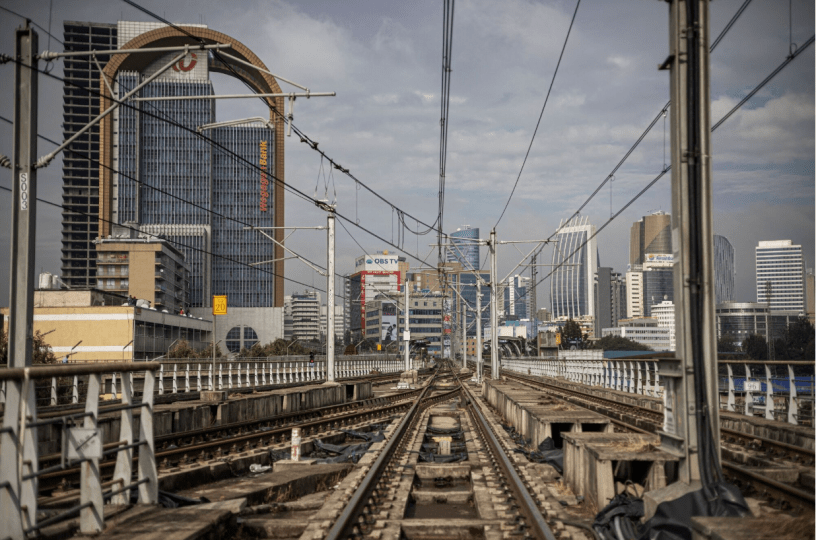

One thing is clear: when you write about Ethiopia or Dr. Abiy, you are upset about the development in Ethiopia, or the PM is doing something great. I think you have heard news that is not what you want to hear, such as the inauguration of GERD, the first phase LNG refinery, the launch of fertilizer plant, the second phase LNG refinery, and the big ones: the mega airport and Pulse of Africa media. These projects are turning your eyes red. But Dr. Abiy’s train that drives Ethiopia’s prosperity is going fast; you can’t stop it with false narratives and disinformation. Period!

This article provides a compelling and human-centered perspective on Ethiopia’s debt crisis. While reforms may appear positive to international creditors, the everyday reality for ordinary citizens is harsh, with soaring costs for essentials like food, fuel, and medicine. It highlights the need for policies that balance financial obligations with social protections. Sustainable debt relief must prioritize the welfare of Ethiopian households to prevent social collapse and restore trust in governance.

Martin Plaut’s continued criticism of Ethiopia can be interpreted as evidence of the significant progress the country is making. His dissatisfaction appears to arise not because Ethiopia is deteriorating, but because it is developing and changing in ways that contradict his long-held negative perspective