The war in Sudan that pits the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) led by General Abel Fattah al-Burhan against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by General Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo – best known as Hemedti – shows no signs of ending.

This, despite intense international efforts to halt the fighting.

The “Quad” which has been trying to resolve the Sudan crisis consists of the United States, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. This coalition proposed a roadmap in September 2025 aimed at ending the conflict in Sudan through a three-month humanitarian truce, followed by a permanent ceasefire, and then a nine-month transitional process to establish civilian-led governance. The Quad’s plan calls for an immediate ceasefire, a humanitarian truce to allow aid delivery, and an inclusive political process.

There is little sign of progress.

Why the war can’t be halted – level one

The war which erupted on 15 April 2023 has pushed millions to the brink of survival, according to the UN.

Over 30 million people now need urgent humanitarian assistance, among them 9.6 million displaced from their homes and nearly 15 million children caught in a struggle for daily survival.

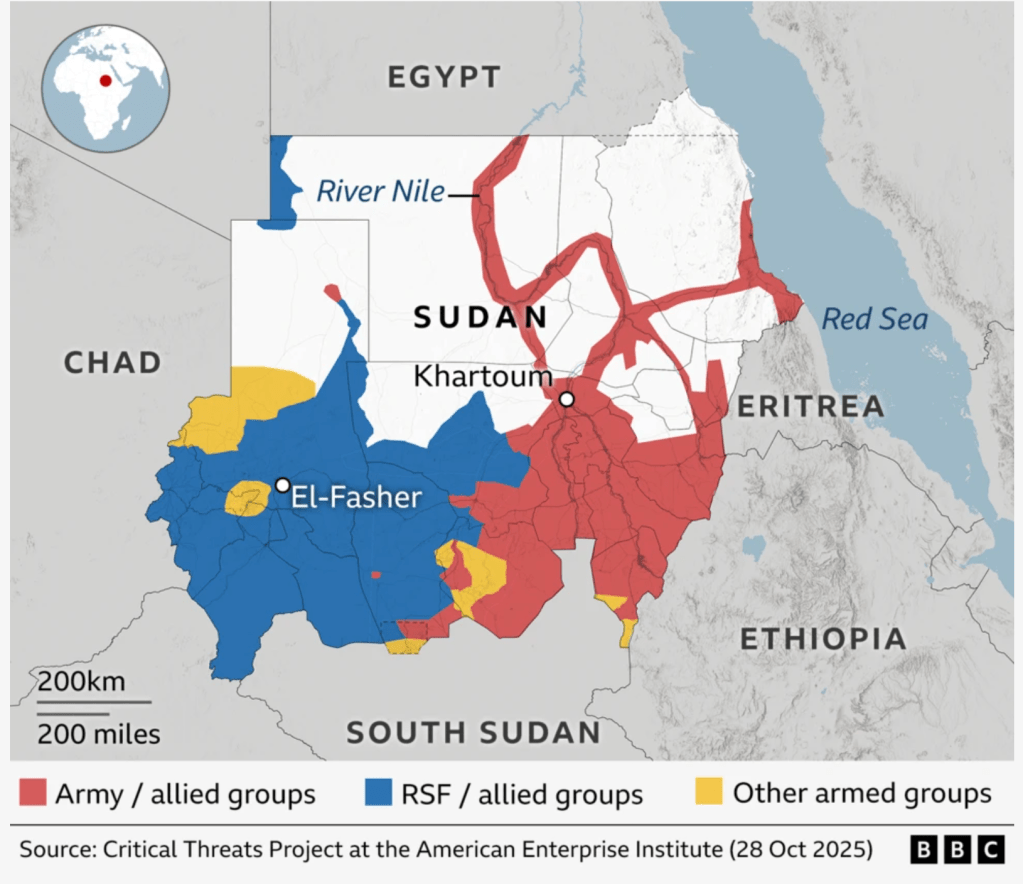

It has left most of western Sudan, bordering on Chad, Libya and the Central African Republic in the hands of Hemedti and the RSF. The centre and much of the east is held by the SAF and al-Burhan.

In one sense, this reflects long-standing tensions: between the people living along the Nile, who generally look northwards to Egypt, and the people of the periphery, who have traditionally been marginalised by the Sudanese elite.

Why the war can’t be halted – level two

If the war is horrific, it has also drawn in too many actors to allow a resolution.

The SAF – and al-Burhan – rely on Egypt, Iran, Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

Egypt is a significant ally of the SAF, recognizing the Sudanese army’s leadership as the legitimate government and is reported to have provided training for SAF pilots and supplied drones, although Egypt officially denies some of these claims.

Iran has supplied drones to the SAF and seeks to use Sudan as a strategic logistical base related to its interests in the Red Sea region.

Turkey has also supported the SAF with drones and various warheads, aiming to maintain influence and secure access to the Red Sea.

Saudi Arabia leans toward supporting the SAF given its interest in the region’s stability.

Hemedti and the RSF. They are backed by the warlord in eastern Libya, General Khalifa Haftar. The area Haftar controls allows the UAE to fly vast quantities of aid – military and humanitarian – to Hemedti. The UAE is his most important backer.

“The RSF is but one of the nodes in a network of non-state actors the UAE has curated over the past decade.” Andeas Krige.

Below is a detailed article outlining how the UAE flies in supplies via Puntland in Somalia, but other routes, including Uganda have been used.

In return Hemedti pays the UAE from the gold he extracts from mines he controls along the border. Once a camel trader, he has become immensely rich.

In the past the Russians supported the RSF, via the Wagner Group, but this appears to have fallen away.

Race as a factor

There is a racial element that underlies the RSF: African ethnic groups in the Darfur area are regarded by the Barggara, of whom Hemedti is one, as “enslaveable”.

The Baggara Arabs traditionally regarded certain African tribes in Darfur and surrounding regions as “enslavable,” particularly those groups who were non-Arab and often of darker skin and different cultural backgrounds. Key tribes that were targeted for enslavement by the Baggara included various Nilotic and other indigenous African groups in the region.

This included groups such as the Fur (though also rulers of Darfur), Zaghawa, and especially the Fur’s southern neighbors and more peripheral groups in Dar Fertit, who were often labeled as “Fertit” or people from the forest zone, seen as more vulnerable to enslavement.

The Baggara, as nomadic Arab cattle herders, traditionally practiced slave raids primarily targeting African farming and village communities whom they viewed as inferior and socially subordinate. These slave raids were a longstanding practice connected to the economic system and social hierarchy of the region, reinforced over centuries by warfare, raiding, and trade.

Thus, the “enslavable” groups were primarily African ethnic groups living in Darfur’s southern and peripheral zones, typically those who were non-Arab, and who had less political power or military strength, making them vulnerable to capture and enslavement by the Baggara.

In this the Baggara are little different from the Fulani, who are spread across much of the Sahel, and who founded the Sokoto Caliphate in Niger and Nigeria, which had at least 2 million slaves when it was finally destroyed by Britain in 1903.

There is strong evidence that the RSF has taken out and butchered men and women purely because of their race.

Why the war can’t be halted – level three

If the West really wanted to end the war it could. But many nations are too engaged with the UAE to take on the powerful families who control the emirates.

The UAE’s western allies, particularly the United States and the UK, have made several significant commitments and promises to the UAE centered around security, economic partnership, and technological cooperation.

Security and Military Cooperation

•The UAE is a close and capable military partner for the United States in the Arab world. This includes deployments alongside US forces in coalition counterterrorism, stabilization, and peacekeeping missions, provision of logistical support for US troops, aircraft, and naval vessels, and hosting joint training exercises.

•The UAE hosts the Joint Air Warfare Center and contributes to combating extremist groups like Al Qaeda and AQAP, as well as supporting a peaceful transition in Yemen and fighting terrorism finance networks.

•The US-UAE defense cooperation agreement, renewed for 15 years, includes the stationing of thousands of American soldiers and massive arms contracts to enhance UAE’s military capabilities.

•France also remains a significant military ally with a base in Abu Dhabi and arms supply relationships.

Economic and Technological Promises

•The UAE-US bilateral trade is robust, exceeding $34.4 billion in 2024, supporting over 161,000 US jobs in sectors like aviation, healthcare, and infrastructure.

• The UAE remains committed to the Abraham Accords, promoting peace and cooperation in the Middle East, while condemning terrorism and extremism. It has taken a firm stance supporting peace initiatives in the region, including calls for ceasefire and humanitarian aid in Gaza.

Britain and UAE also have long standing security and defense collaborations. Since the signing of a Defence Cooperation Accord in 1996, their armed forces have worked closely to ensure stability in the Arabian Gulf region. The UK provides military training, defense technology, and intelligence-sharing, which bolster the UAE’s security capabilities.

In summary, western allies have promised strategic military support, deepened economic ties, advanced technological cooperation, and sustained diplomatic backing aimed at regional stability and prosperity with the UAE as a central partner.

Putting these ties at risk to pressurise the UAE to end its support for the RSF appears implausible.

For all of these reasons it is difficult to see the war in Sudan ending: too many forces are involved and too many futures are at stake.

Exclusive: Inside the UAE’s secret Sudan war operation at Somalia’s Bosaso

Source: Middle East Eye

Colombian mercenaries, regular transport flights and cargo marked ‘hazardous’ reveals a vast covert operation fuelling the RSF massacres in el-Fasher

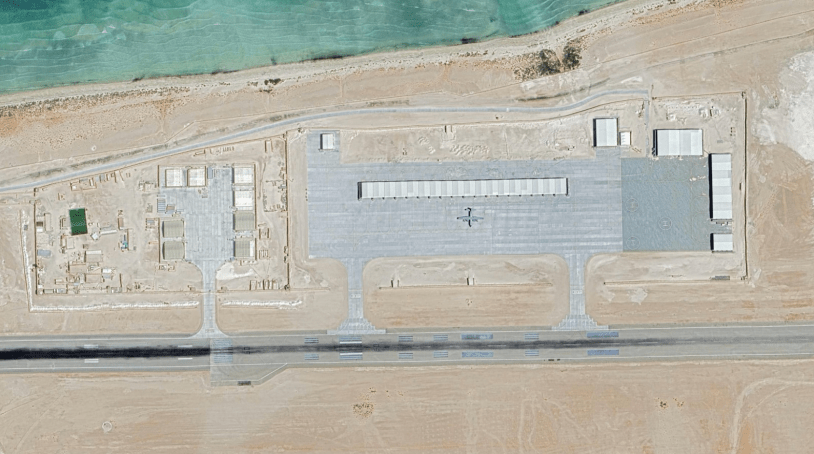

Bosaso, on the Puntland coast of Somalia, has become key to the UAE’s support of the RSF in Sudan (Supplied)

Published date: 31 October 2025 11:13 GMT

At Bosaso Airport in Somalia’s Puntland state, the thunderous sound of large aircraft hitting the tarmac echoes out across the port city.

Minutes after landing, the aircraft can be identified. It is a white IL-76 heavy cargo transport plane, and it is parking next to a very similar aircraft.

For local residents, the sound of such planes was unusual two years ago, when they first began landing in Bosaso. Not anymore. Moments later, undisclosed heavy logistical materials are seen being offloaded from the aircraft.

“They’re frequent and the logistics are transferred immediately to another aircraft that is on standby and is destined for the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan through the neighbouring countries,” said Abdullahi, a senior Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) commander at Bosaso Airport, who spoke to Middle East Eye using a different name for security reasons.

According to flight tracking data, satellite imagery, multiple local sources, and US and regional diplomats, the origin of these planes and their cargo is clear: the United Arab Emirates.

The destination, as Abdullahi said, is Sudan and the RSF, which this week has captured el-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state, after over 500 days of siege. The paramilitary’s fighters have committed terrible atrocities in the wake of their triumph, filming themselves massacring fleeing civilians and carrying out mass executions at hospitals.

Over a period of months, a pattern could be seen in the cargo aircraft tracked by MEE coming into Bosaso.

The planes would not remain long at the airport and would arrive during periods of minimal activity at the airport. Publicly available air traffic data shows that the UAE increasingly uses Bosaso Airport as the arrival times of the aircraft are sometimes changed.

“During loading and offloading, they are heavily guarded, as they carry sensitive materials and logistics that are not publicly disclosed,” Abdullahi said. Supplies also come into the port at Bosaso.

For years, the UAE has been funding Puntland’s PMPF, a regional force established to combat piracy. The soldiers there say none of the materiel arriving on transport aircraft is brought to their camp, as the shipments are large and beyond their requirements.

Flight tracking data previously reported by MEE has revealed that the UAE has significantly increased the supply of weapons into Bosaso, with US intelligence saying that these include Chinese-made drones.

A senior manager at Bosaso’s port revealed for the first time to MEE that, for the past two years, the United Arab Emirates has funnelled over 500,000 containers marked as hazardous through Bosaso.

Unlike standard cargo, which is documented with a letter of origin and destination, these Emirati shipments have no description of their contents. The port manager said that the logistics operations are shrouded in secrecy: upon arrival, the containers are swiftly transferred to the airport and loaded onto standby aircraft.

Security for these shipments is exceptionally tight, MEE’s sources in Bosaso said. When a ship docks, PMPF forces are deployed to cordon off the port and prevent filming. Only personnel on duty are granted access, and they are explicitly warned against recording anything during the offloading and transit process.

The sources contended that the clandestine nature of the operation proves the goods were not for domestic use.

“If they were, we would see where they were stored or find the empty containers,” the senior manager said. Instead, he said, “it was just transit”, meaning that Bosaso was a covert stopping point.

Middle East Eye wrote to the government of the UAE and to regional authorities in Puntland requesting a response. Neither replied. The UAE has previously denied sponsoring the RSF.

Colombian mercenaries

Located on the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden, Bosaso airport hosts several heavily fortified military facilities, including one occupied by UAE commanders and security personnel believed to be South Africans.

To the north of the airport lies a separate camp housing Colombian mercenaries involved in the war in Sudan.

Pictures exclusively obtained by MEE show dozens of Colombians carrying backpacks disembarking from an aircraft at Bosaso airport and heading directly to the camp.

When shown the images, Abdullahi immediately recognised them, saying: “Yes, they’re Colombian mercenaries operating from here in large numbers.”

The Colombian personnel arrive in Bosaso on international commercial flights, transiting through the airport almost every day before continuing on to Sudan, where they fight alongside the RSF.

Somali soldiers from the PMPF, who are stationed at the airport, rarely have access to the Colombians’ camp. Abdullahi explained that “the mercenaries have built a new hospital within their compound, which they use to treat soldiers wounded in Sudan.

“I recall one occasion when a plane carrying injured soldiers landed at Bosaso airport and the aircraft door was visibly stained with blood,” he said.

The maritime police officer told MEE that the camp also serves as a medical transit point for wounded RSF fighters, who are later flown to other destinations for further treatment.

Just next to the airport, the United Arab Emirates has installed a military radar system – believed to be French – designed to protect Bosaso airport from potential attacks.

As MEE reported recently, Bosaso is connected to a ring of bases built and expanded by the UAE across the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea. The bases, on the islands of Mayun, Abd al-Kuri, Samhah; at the Somaliland port of Berbera and the Yemeni port of Mocha, are all on territory nominally controlled not by the UAE but its allies or clients.

Soldiers stationed in Bosaso say the presence and activities of Colombian mercenaries in the area have become increasingly concerning, leaving many PMPF soldiers feeling unsafe.

“We believe there is a high risk that the Sudanese government could target activities at Bosaso airport,” said Abdullahi.

‘A plane carrying injured soldiers landed at Bosaso airport and the aircraft door was visibly stained with blood’

– Abdullahi, Puntland Maritime Police Force officer

Before Sudan’s war began in April 2023, the country offered scholarships to thousands of Somali students, with one of the notable beneficiaries of this scheme being Somalia’s current defence minister, Ahmed Moallim Fiqi.

Several Puntland Maritime Police Force soldiers admit they are uneasy about cooperating with the foreign personnel involved in the Sudan war, fearing their work might indirectly support a genocide against a country they consider a close ally.

At the beginning of the year, the US government determined that the “members of the RSF and allied militias have committed genocide in Sudan”, a conclusion that has been reached by many human rights groups.

“I believe it’s morally unacceptable to assist mercenaries engaged in fighting a nation that has long supported Somalis – including members of my own family,” the soldier said.

Somalia and the UAE

For years, the United Arab Emirates has provided financial assistance to Mogadishu and trained Somali soldiers to combat armed groups such as al-Shabab.

But this relationship has darkened significantly in recent years, as the UAE has aided and abetted regional administrations like Puntland and Somaliland, which have designs on splitting away from Somalia.

‘Mogadishu is unable to object, given that it is unprepared to counter the UAE’s expanding influence’

– Abdirashid Muse, analyst

Mogadishu maintains control over Somali airspace and authorises all flights into the country, but it has no authority over Bosaso’s port and airport.

Despite the uneasy relationship that exists between Hassan Sheikh, Somalia’s president, and the UAE’s Mohammed bin Zayed, the government in Mogadishu has not openly confronted Abu Dhabi over its military activities in Puntland.

“Mogadishu is unable to object, given that it is unprepared to counter the UAE’s expanding influence,” said Abdirashid Muse, a regional analyst and critic of the UAE’s activities in the Horn of Africa.

He agrees with Abdullahi, noting that the UAE’s activities in Bosaso are deeply concerning, as they risk drawing Somalia into broader geopolitical rivalries among regional powers.

Puntland’s state president, Said Abdullahi Deni, is widely regarded as a close ally of the UAE, largely due to the financial support that could strengthen both his administration and his political ambitions.

How the UAE built a circle of bases to control the Gulf of Aden

Meeting the UAE’s Deputy Prime Minister Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan recently, US President Donald Trump laughed and referred to him, on camera, as having “unlimited cash”.

Martin Plaut, an academic specialising in conflicts in the Horn of Africa, said the UAE’s involvement in the war in Sudan is driven primarily by its interest in obtaining gold and expanding regional influence.

In the case of Puntland, he said its strategic location and relative independence made it an ideal operational base for the UAE.

“Puntland remains one of the least surveyed and overseen areas in the world. It’s simply a convenient place for the UAE to operate from – and nobody is going to ask them any questions,” Plaut told MEE.

In July, Deputy Prosecutor Nazhat Shameem Khan of the International Criminal Court (ICC) told the UN Security Council that the ICC has “reasonable grounds to believe” that both war crimes and crimes against humanity are being committed in Sudan.

“Puntland authorities could be complicit and may have a case to answer,” said Plaut.