Getachew Reda’s apparent attempt to balance political survival with rhetorical restraint risks normalising the very impunity that devastated Tigray. Ambiguity may buy political space, but it does so at the expense of truth — and at the expense of the victims whose suffering remains unacknowledged by those in power.

Source: Selam Kidane

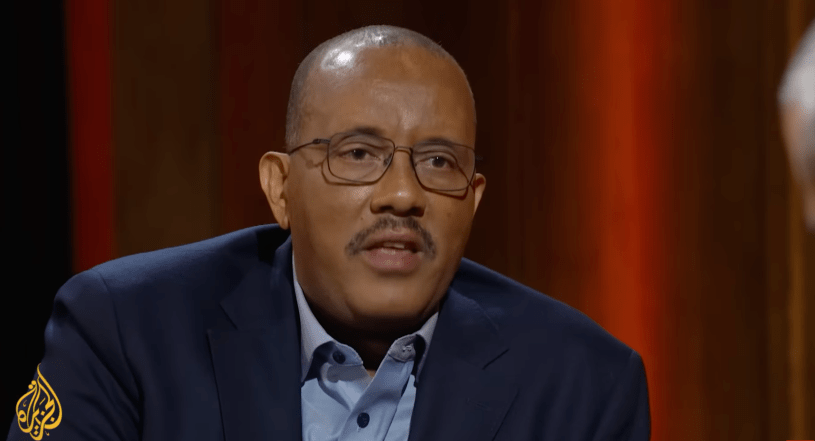

Al Jazeera’s Head to Head is one of the most demanding political stages in contemporary media. It takes courage, and considerable intellectual agility, to sit opposite Mehdi Hasan, whose interrogation style leaves little room for evasions or rhetorical manoeuvre. To appear on that platform is to invite scrutiny of the highest order. Under such conditions, Getachew Reda demonstrated notable poise. He maintained his calm under pressure and navigated Mehdi Hasan’s rapid-fire questioning with the discipline of a seasoned political actor. In almost any other context, his performance would have been considered strong enough.

But that is precisely where the deeper concerns begin.

For those of us who have lived through or studied the impact of the war in Tigray, Getachew’s sudden ambiguity around the genocide was deeply disquieting. This was not merely a shift in tone; it was a retreat from clarity. His framing that “crimes related to genocide” occurred, but accountability should be left to courts without naming the individuals responsible felt like an intentional blurring of lines that were once drawn boldly and unequivocally.

More troubling still was his argument that the region faces no imminent threat of renewed war because the leaders involved now possess “ hearts.” This line of reasoning collapses under the weight of recent history. These very leaders did not display such benevolence when atrocities were unfolding, when civilians were being targeted, or when the humanitarian blockade starved a region. If their moral restraint did not prevent the original descent into violence, on what grounds should we trust it now?

To insist that future peace rests on the goodwill of those who presided over catastrophic harm is to detach analysis from evidence and to confuse hope with historical amnesia.

And yet, there is a layer of complexity that must be acknowledged. Getachew Reda is operating in a political context where survival, literal and political, is not guaranteed. It is conceivable that he is attempting to chart a new path: one that does not yet exist, but which he hopes might emerge if he remains close enough to the levers of power. Perhaps he believes that by staying alive and maintaining a presence within Ethiopia’s political architecture, he may eventually influence the implementation of the Pretoria Agreement or push for some form of accountability from within.

That interpretation is understandable. But it does not make his current position principled! nor does it make it convincing!

There are moments in political history where pragmatism becomes a necessary tool, and others where pragmatism becomes indistinguishable from complicity. The pursuit of justice after genocide does not lend itself to the “art of the possible.” Justice is not a negotiation; it is a moral imperative. If the road toward justice has become blocked, diluted, or rendered politically impossible, the solution is not to shift the moral goalposts or soften the vocabulary around atrocity.

In such moments, integrity demands one of two paths:

either to call out the injustice clearly, even at personal cost, or to acknowledge the limits of one’s position and continue advocating from a less powerful but more principled place.

Getachew Reda’s apparent attempt to balance political survival with rhetorical restraint risks normalising the very impunity that devastated Tigray. Ambiguity may buy political space, but it does so at the expense of truth — and at the expense of the victims whose suffering remains unacknowledged by those in power. When justice is deferred indefinitely, it risks becoming permanently out of reach.

Accountability for the genocide in Tigray cannot be left to vague promises of future institutions, nor entrusted to the goodwill of leaders who have repeatedly demonstrated that moral restraint is not their guiding principle. Transitional justice requires clarity, courage, and a willingness to confront political realities without capitulating to them.

This is not a call for recklessness, nor a dismissal of the dangers inherent in Ethiopia’s political environment. It is a reminder that certain principles, especially those relating to mass atrocity, cannot be subordinated to political expediency. Justice may be aspirational, but it is also foundational. Without it, there can be no genuine reconciliation, no sustainable peace, and no moral legitimacy for any political actor involved in the aftermath of the war.

Getachew Reda may genuinely believe he is charting an unmarked road toward peace and justice. But roads toward justice are not created through silence, ambiguity, or rhetorical caution. They are forged by confronting truth, naming responsibility, and insisting that the lives destroyed in Tigray are not political inconveniences but moral obligations.

If justice has become impossible within the current structure of power, the response is not to dilute it, but to continue demanding it, from whatever position one holds, however precarious. To do otherwise is to risk becoming an instrument in the erasure of suffering that demands remembrance, accountability, and redress.

Selam Kidane

London

UK