Narratives of historical entitlement to Eritrea’s port of Assab have gained traction in Ethiopia, mobilizing the population around a nationalist agenda, and Addis Ababa and Asmara are increasingly locked in a tense standoff. Yet, a direct confrontation between the two governments remains unlikely. The Ethiopian government has pulled its forces back from positions where their troops could come into direct contact, and Eritrea cannot risk a confrontation that would trigger more international backlash on top of existing sanctions. Nevertheless, both states are expected to keep supporting opposition groups against one another, prolonging the region’s instability.

Source: ACLED

The Houthis have drawn down their attacks on commercial shipping, but dynamics in the Horn of Africa and Yemen bring the Red Sea to a crossroads between de-escalation and spiraling violence.

11 December 2025

Authors

Luca Nevola

Senior Analyst, Yemen and the Gulf

Jalale Getachew Birru

Senior Analyst, East Africa

By the numbers

From 1 January to 28 November 2025:

- Over 9,090 people died in political violence events in Somalia.

- ACLED records 84% fewer Houthi attacks in the Red Sea than in all of 2024.

- 848 people died in US airstrikes in Somalia (320) and Yemen (528).

The Red Sea has been in turmoil since 7 October 2023, and the crisis dragged on throughout 2025. Gaza-related Houthi attacks remained a major driver of insecurity, while new tensions emerged in the Horn of Africa, fueled by the rival ambitions and interference of regional powers.

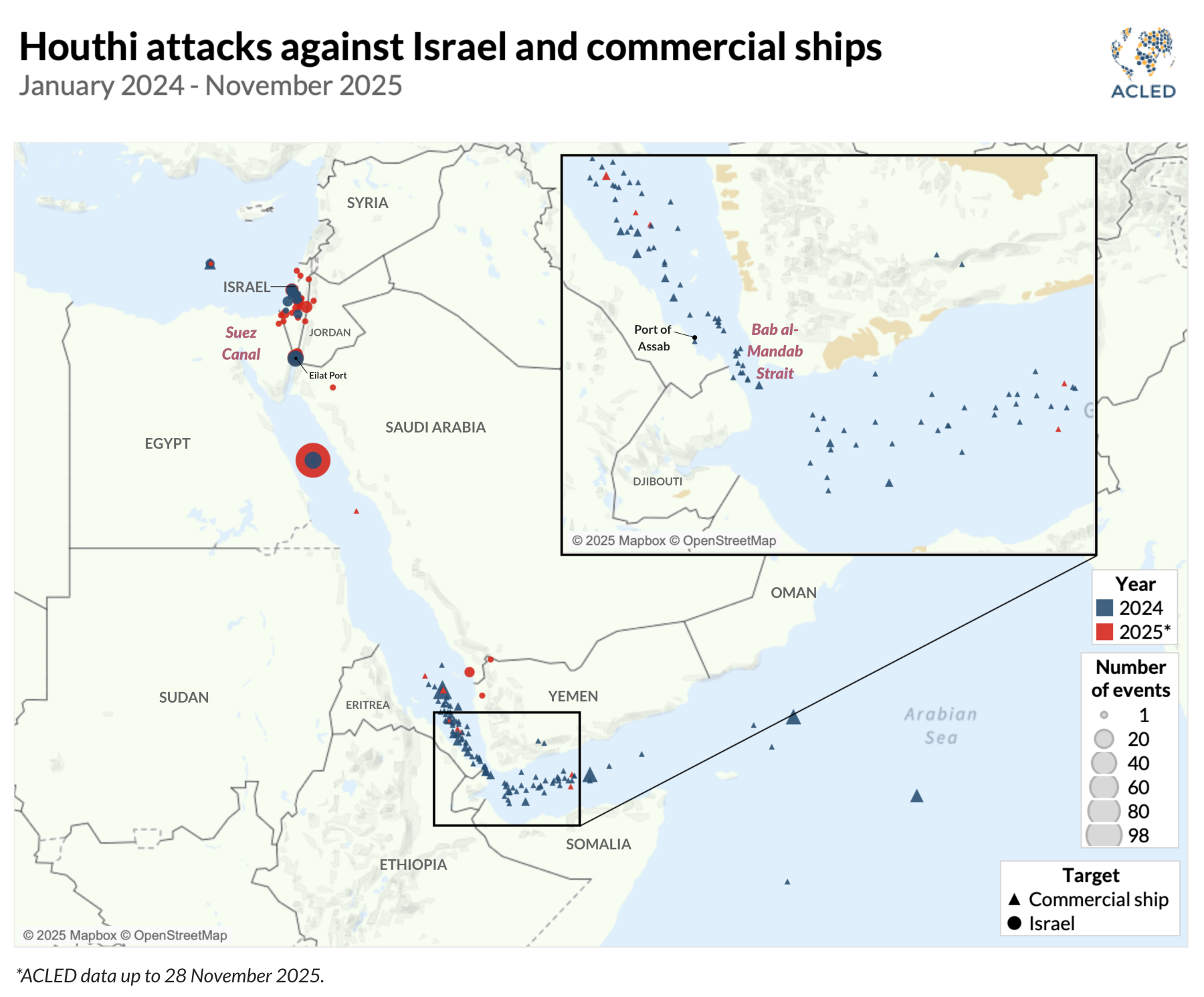

Despite a decline in attacks and a reduced threat to commercial shipping, the Houthis remain a persistent threat (see map below). In 2025, the group shifted its focus to targeting United States warships, prompting Washington to re-designate it as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO)1 and launch a costly air campaign.2 The standoff ended with a ceasefire that produced no clear winners: Attacks on US forces ceased in May, but Houthi long-range capabilities remain intact.

The sharp drop in Houthi attacks on commercial vessels — only 7 in 2025, compared to 150 in 2024 — reflected a strategic recalibration rather than diminished capacity. Their long-range capabilities are evident from the 125 Houthi strikes on Israeli soil in the first 11 months of 2025 — a 120% increase from 2024 — which continued until the Israel-Hamas ceasefire in October 2025. Israel responded with waves of airstrikes on Houthi infrastructure and leadership, pursuing a decapitation strategy that culminated in the decapitation of the Houthi-led Government of Change and Reconstruction in August 2025.

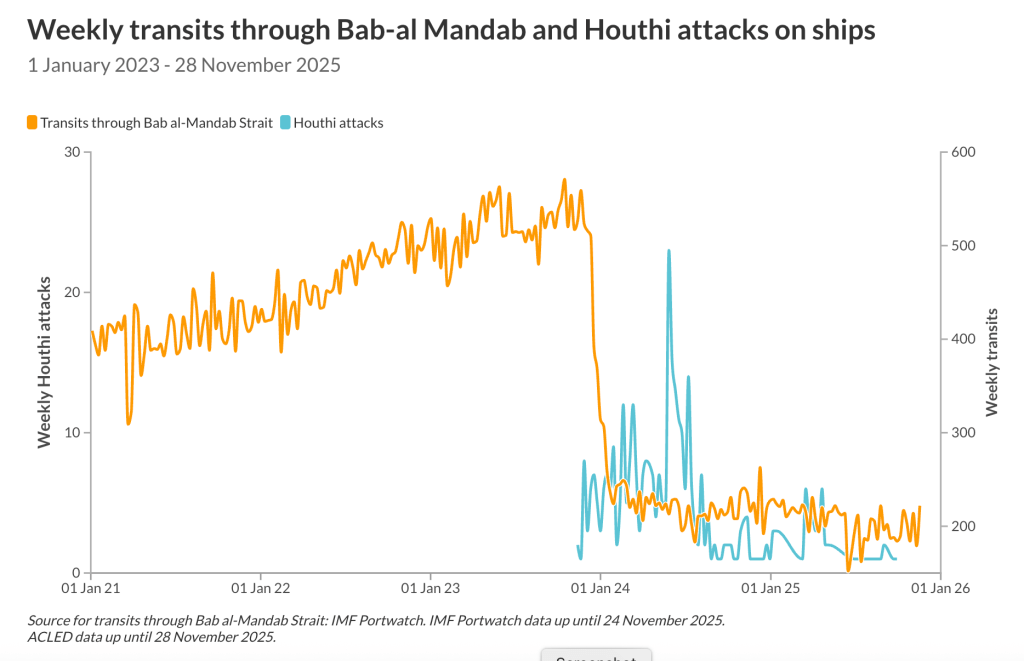

Although Houthi attacks in the Red Sea fell sharply in 2025, commercial traffic has yet to recover: Transits through Bab al-Mandab hit a record low in June 2025 (see graph below) — down 65% from June 2023 — Eilat port halted operations in July, and Suez Canal revenues dropped. This is because the Houthis’ real strength lies not in the volume of their arsenal but in their ability to sustain a high perception of risk.

Houthi long-range capabilities are enabled by Iran and rely on smuggling routes running across the Red Sea from the Horn of Africa.3 These routes have become increasingly two-way, with growing coordination between the Houthis, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), al-Shabaab, and Islamic State (IS) Somalia, as Somali groups trade smuggling support and maritime intelligence for weapons and technical expertise.4 The intensification of smuggling in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden has elicited a strong response: In April, the US Africa Command reported having carried out airstrikes on a stateless vessel carrying conventional weapons in Somali territorial waters.5 Thanks to its role at the heart of a transnational smuggling network, IS Somalia is reported to serve as the financial hub for the wider IS organization.

The Red Sea basin has, however, turned into a hotbed of broader instability and geopolitical competition. In the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia’s push to secure Red Sea access is stoking fears over a new war with Eritrea. Addis Ababa’s claims over Eritrea’s port of Assab in 2025 prompted both countries to mobilize forces and back rebel groups along their shared border.6 Ethiopia’s ambitions have also drawn in Egypt, which is already at odds with Addis Ababa over the Nile dam. Cairo has responded by reinforcing political and military support to Somalia and Eritrea, insisting that only littoral states should control Red Sea access.

Amid ongoing turmoil on both shores of the Red Sea, outside powers compete for political, military, and commercial influence. Qatar, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, along with Saudi Arabia and Egypt, have signed security pacts with regional capitals and provided military support to state and non-state armed groups across the region in exchange for lucrative contracts and political clout.

2026 offers a narrow window for stability in the Red Sea, but it will require regional coordination

The Red Sea stands at a crossroads: The tensions of 2025 could either spiral into renewed conflict or give way to a fragile stabilization, as the region shows signs of both de-escalation and strain.

The 10 October Israel-Hamas ceasefire raises questions about the future of Houthi operations. The group portrayed its Red Sea attacks as acts of solidarity with Palestine, aimed at pressuring Israel to end its campaign in Gaza. Now, the Houthis have paused attacks on Israel, but warned they will retaliate if full-scale operations resume.7 Should the ceasefire collapse, the group would likely resume attacks on Israeli territory, reserving strikes on commercial vessels for more strategic objectives.

The current halt in attacks is positive for regional stability, but it does not change the overall equation: The Houthis still retain long-range drone and missile capabilities that have reshaped the Red Sea’s balance of power and continue to pursue ambitious post-Gaza goals — defeating Israel, “liberating” al-Aqsa, and asserting control over regional waters.8 Furthermore, the group has emerged as a pivotal force within a now-weakened Axis of Resistance, filling the vacuum left by the waning influence of other players in the network. Iran has recently stepped up its transfer of weapons and expertise,9 expecting the Houthis to intervene on its behalf if needed. This alignment is clear in recent Houthi operations, which increasingly respond to events unrelated to Gaza, such as the 12-day war with Iran or the UN “snapback” sanctions.10

Within this framework, the pragmatic cooperation between the Houthis, AQAP, al-Shabaab, and IS Somalia — currently centred on arms exchanges11 — could evolve into a strategic, Iran-backed network capable of heightening regional instability and exerting leverage over both regional and international powers.12 In Yemen, the halt in hostilities between the Houthis and AQAP is holding, while operational coordination is evolving and smuggling networks are expanding along the route linking them to al-Shabaab.13 Islamist groups in the Horn could emulate the Houthis by adopting drone technology to threaten navigation, while the influx of smuggled weapons risks boosting their operational capacity and weakening Somali and African Union stabilization efforts.

Against this backdrop of expanding militant networks and cross-Red Sea coordination, international tensions in the Horn further compound instability. Narratives of historical entitlement to Eritrea’s port of Assab have gained traction in Ethiopia, mobilizing the population around a nationalist agenda, and Addis Ababa and Asmara are increasingly locked in a tense standoff. Yet, a direct confrontation between the two governments remains unlikely. The Ethiopian government has pulled its forces back from positions where their troops could come into direct contact, and Eritrea cannot risk a confrontation that would trigger more international backlash on top of existing sanctions. Nevertheless, both states are expected to keep supporting opposition groups against one another, prolonging the region’s instability.

Still, it’s not all bleak — the Red Sea also shows signs of progress and opportunity. The Israel-Hamas ceasefire could pave the way for peace negotiations in Yemen. With regional powers showing little appetite for renewed military intervention, the halt in Red Sea attacks is creating space for the Houthis and Riyadh to resume discussions on the United Nations peace roadmap. Any agreement will need to include firm guarantees that the Houthis will not resume Red Sea attacks and may also open the door to lifting the FTO designation.

Increasingly eager to present itself as a regional mediator,14 Saudi Arabia could seize the current momentum to revive discussions on establishing a body to coordinate security in the Red Sea — an idea first pursued with the Council of Arab and African Coastal States of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in 2020. At the same time, Riyadh, together with the US, the UAE, and Egypt — the so-called Quad — is working to mediate between the Rapid Support Forces and Sudanese Armed Forces in an effort to secure a ceasefire and support a sustainable peace in Sudan.

Without genuine coordination, the region will remain acutely vulnerable to proxy competition, sudden escalations, and disruptions to global trade, as Gulf actors, Horn of Africa governments, and international powers pursue competing agendas and rely on local groups with their own ambitions. The current pause in hostilities offers a narrow window to stabilize the region. Whether the actors seize it will determine if the Red Sea moves toward lasting de-escalation or slides back into instability with even higher stakes.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco.

Somalia, Ethiopia, and Yemen rank among the top 20 countries with the most deadly political violence in the world.

Ethiopia and Eritrea: What is the possibility of war? — Expert Comment

A direct confrontation between Ethiopia and Eritrea is unlikely despite the threat of military action in both countries. ACLED

26 March 2025 Author

Clionadh Raleigh

President & CEO

ACLED’s CEO, Prof. Clionadh Raleigh, said: “The lines of this potential conflict are too fragmented, and there is more smoke than fire. The prevailing idea seems to be a rising contest between Eritrea and Ethiopia in and over Tigray, which the Ethiopia National Defense Force (ENDF) withdrew from in February. The ruling Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) party is incredibly and dangerously fragmented, and the non-ruling fragment is making a lot of noise. Although the faction has never admitted it, much is being made about their possible opportunistic alliances with the (former and current enemy) Eritrean government on one hand and fragments of the (former and current enemy) Amhara nationalist militias — Fano — on the other hand. So who would fight whom over what is as confusing and unlikely in Tigray as it is outside of the region.”

The complex dynamics are addressed below.

Background

The TPLF’s internal rift has been escalating since the start of the year. The escalation came on the heels of an ultimatum that the National Election Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) issued on 26 December 2024 urging the TPLF to convene its general assembly meeting — a key step in the group’s path to re-registration as a political party — before the 10 February deadline.

Signs of disagreement among the TPLF’s top leaders emerged only days after the TPLF and the Ethiopian government signed the Pretoria agreement, which ended the Tigray war, in November 2022. Divergences over the implementation of the peace agreement resulted in two factions emerging.

One faction is loyal to the president of the Tigray Regional Interim Administration, Getachew Reda, and advocates for the TPLF to concentrate on determining accountability for the devastation in Tigray resulting from the conflict.

The “old guard” faction, aligned with TPLF party President Debretsion Gebremichael, instead prefers to begin the internal assessment from the establishment of the interim administration in March 2023 and focus on the activities of the interim administration.1

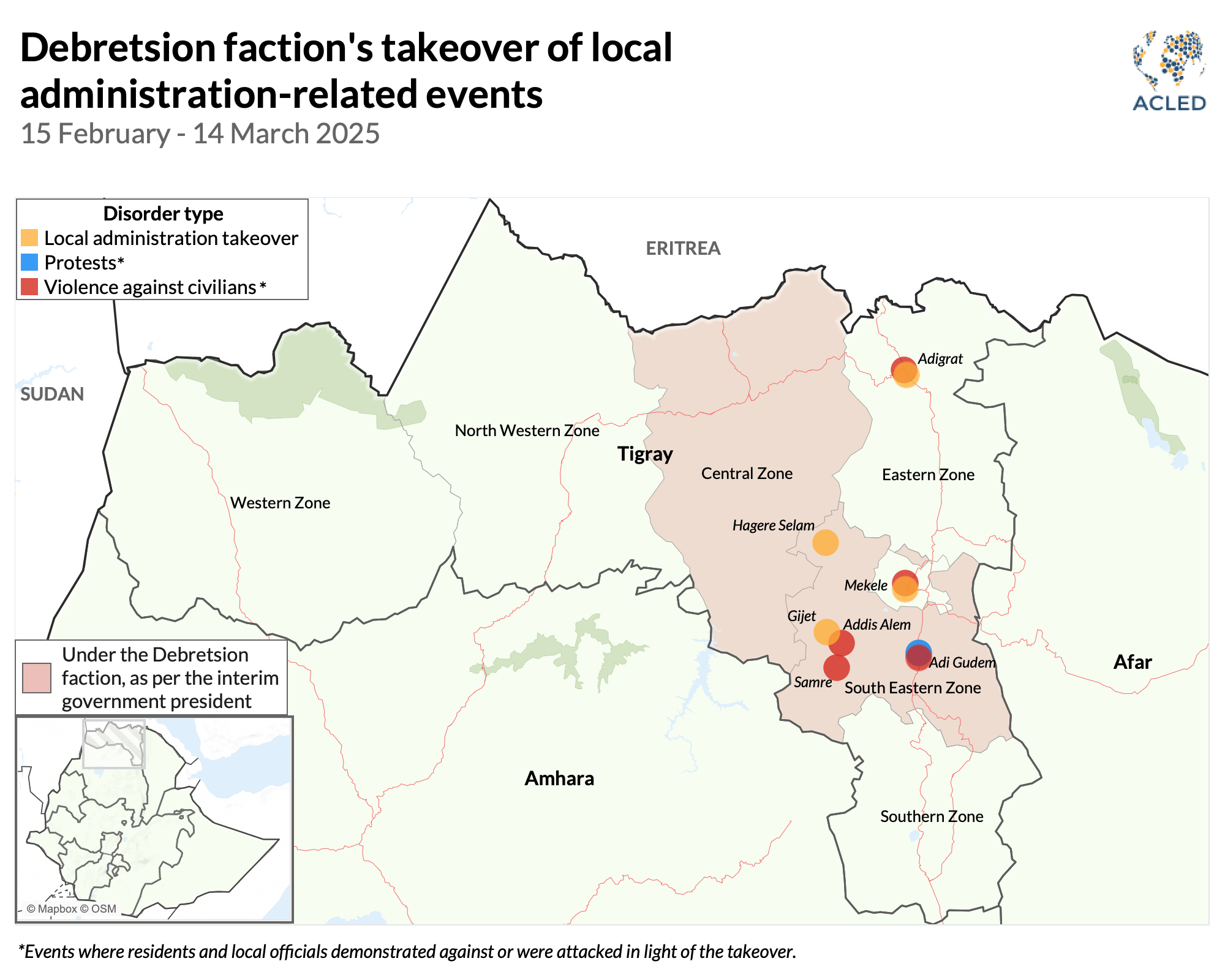

The NEBE’s December 2024 statement forced the Debretsion faction to step up its efforts to capture the interim administration. Since mid-February, members of the Tigray Defense Forces who support the Debretsion faction began to forcefully confiscate local administrations’ official seals and take control of administration offices (see map below; for more, see the Ethiopia situation update (5 March 2025) and Ethiopia situation update (19 March 2025)).

Will the real TPLF please stand up?

Getachew Reda, who leads the ruling faction in the TPLF split, has accused the Debretsion faction of colluding with the Eritrean government to initiate a war between Ethiopia and Eritrea on a number of occasions since last year.2 On 17 February, the former president of Ethiopia also accused the Eritrean government of trying to take advantage of the TPLF’s internal dispute to incite war in Ethiopia.3 The Eritrean government responded by expressing that it has no interest in the TPLF internal dispute and accusing the Ethiopian government of planning to invade Eritrea to gain access to the Red Sea4 (for more on Ethiopia’s quest for sea access, see this report). Since then, many reports have indicated the high possibility of war between the two countries.5

The main assumption

Many observers believe the Eritrean government is collaborating with members of the Debretsion faction and Fano militias — which are fighting the Ethiopian government in the Amhara region — to attack the Abiy Ahmed-led government.

Why might this be an accurate assumption?

There are signs of possible conflict in the Tigray region, just as there were before the start of the two-year war in northern Ethiopia, like the Eritrean forces’ mobilization6 and the Ethiopian government showing the public various acquired and produced weapons.7

Why might it be inaccurate?

Unlike the two-year war in Tigray, the Debretsion faction lacks massive support from the residents of the Tigray region and the Tigrayan diaspora, who have not yet recovered from the war. Hence, reigniting a new round of conflict with the Eritrean government’s support will defy the faction’s main purpose, as it seeks to regain support from the Tigray people. The Debretsion faction also lacks support from the international diplomatic community.

Fano militias are also weak and are struggling to come under one umbrella due to their structure and lack of common ideology. Basically, these factions are making a lot of noise about how strong they are.

The possibility of war

A direct confrontation between Ethiopia and Eritrea is unlikely despite the threat of military action in both countries.

There is an indication that the ENDF is trying to avoid a direct confrontation. According to Getachew, the ENDF withdrew from major towns in Tigray in February.8 The Ethiopian government’s tactic is to avoid being stationed in areas surrounded by potential adversaries to avoid a direct confrontation.

The Eritrean government also cannot afford a direct confrontation with the ENDF due to repercussions from the international community on top of current sanctions by various governments.

ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data) is an independent, impartial, international non-profit organization collecting data on violent conflict and protest in all countries and territories in the world.

Footnotes

- 1Lewam Atakelti, “‘We will save the party by peacefully and legally eliminating the TPLF wing that held the conference,’” Reporter, 2 October 2024 (Amharic)

- 2YouTube @fanabroadcastingcorporate, 13 March 2025 (Amharic)

- 3Mulatu Teshome Wirtu, “To avoid another conflict in the Horn of Africa, now is the time to act,” Aljazeera, 17 February 2025

- 4X @hawelti, 18 March 2025

- 5Nosmot Gbadamosi, “Tigray Power Struggle Risks Ethiopia-Eritrea War,” Foreign Policy, 19 March 2025

- 6Borkena, “Eritrea Mobilizes Military Reserves, Imposes Travel Restrictions Amid Rising Tensions with Ethiopia,” 21 February 2025

- 7YouTube @EBCworld, 8 March 2025 (Amharic)

- 8YouTube @Reyot, 17 March 2025 (Amharic)