There were many South African heroes who fought and finally defeated apartheid. But for me Zora Mehlomakulu is the most memorable, yet she is little known.

A fine obituary was written about her, which is at the end of this article, but here is my view.

Martin

By the 1970’s the black unions had been all but extinguished by attacks over the previous decade by the authorities. The African National Congress and its union arm – the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) – had decided that the only path ahead lay through armed struggle. They went into exile, establishing training centres in Tanzania, Zambia, Angola and Mozambique. But some SACTU activists had been jailed or had decided not to flee abroad. They went quiet. Gradually they were joined by those who were freed from prison.

Without unions the pay of African workers fell until they could truly be described as “starvation wages.” It was a scandal that had to be addressed. It was something that Zora Mehlomakhulu felt acutely.

Mehlomakhulu was born on the 11th of April 1940 in the township of Langa, on the outskirts of Cape Town and joined SACTU in 1963.

She was detained in the same year as the crackdown against the unions and the ANC intensified. Zora decided to remain in the Cape rather than go into exile, only to become active again in the 1970’s. She never denied her SACTU heritage but did not see her later activities as a simple extension of the past. In her view the new forms of organisation were in a different mould: ‘I would say…they are actually in place of SACTU.’

Her determination to become re-engaged in the 1970’s was driven by a determination to continue the fight. As she put it, the decision by the former activists was taken: ‘[By] of ex trade unionists that were banned and house arrested and who actually felt that workers were defenceless. And anyway they had not reached their goal. Something had to take the place in the line of helping workers organise. And how that was going to take place…nobody actually had the right pattern, so our beginning was starting it as a small advice bureau…we had to be cautious of another crush by the government.’

By the early 1970’s white students at universities in Durban, Cape Town and Johannesburg were coming to the same conclusion. They established a series of what were called “Wages Commissions” to campaign for better pay. The students were not sure how to do it, but believed that unions and worker organisation were the way forward.

This was the background to the first planning meeting of the University of Cape Town Wages Commission on 19th November 1972. One of the students, Gordon Young recalled: ‘We started with a concern about poverty. Wages were extremely low so from welfare we came to poverty and saw workers in very shocking conditions… migrant workers… our first campaign as the Wages Commissions was an anti-poverty campaign, but we were beginning to learn that unlike other poor groups in society workers had some potential power… workers did have an opportunity to combine, which squatters or paraplegics or children did not have.’

The beginning

To make this work, the students decided to reach out to the former SACTU activists from the 1950’s and 1960’s – of whom Zora was one. While this work was under way other events took place, of which the students were initially unaware. Meetings were held in the townships of Cape Town in mid 1972 of several people whose bannings had expired. Zora explained that their aim was to decide what to do about unionisation.

‘So a decision was made that trade unions should be started again in the Western Cape, but not under the South African Congress of Trade Unions. And there was a problem of financial resources that we had. Just at the time we came to know about the Wages Commission and then decided after several meetings that we approach them and see what can come of our meetings. So in middle ’72 we did and that is how we came across people who were actually prepared to assist in the initial stages of the whole thing.’

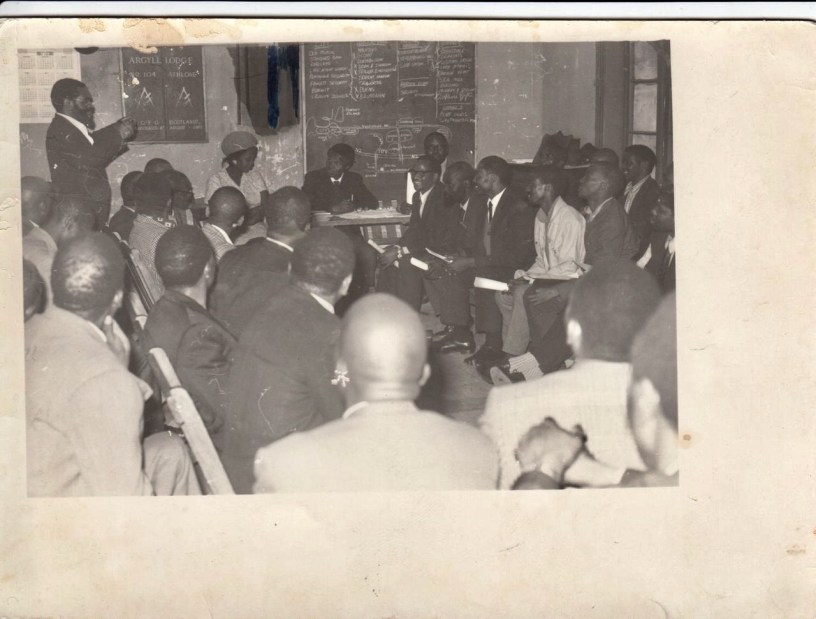

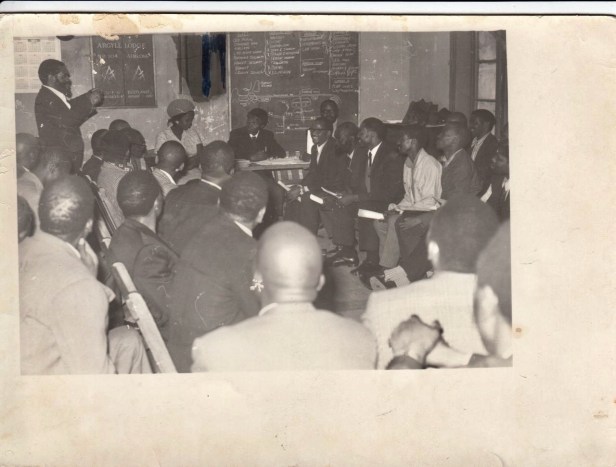

There were preparatory meetings of the Wages Commission in 1972 and then again in January 1973. In the end it was decided to establish the Western Province Workers’ Advice Bureau (WPWAB). It’s aim was to provide advice and help workers organise at Cape Town factories and on the docks. It was formally launched on 9 March 1973, with the constitution presented to workers ‘for their consideration.’

The movement grew slowly at first. The work was hard and slow, and the cost was high, with several people arrested and banned. But it did succeed. Within four years it had the backing of 5,000 workers.

This way of working was embraced by Zora.

Strategy and Tactics

‘We decided to start an advice office and not a union. The Minister of Labour was hard on unions at that time because the workers were still weak. The government wanted committees for the workers — not unions. When the Western Province Workers Advice Office started, we had nothing. We even borrowed a desk and a chair. Times were hard. The workers were scared. They thought unions led to trouble. The bosses were hard too. They used to throw us out — or call the police.’

Zora adopted simple tactics to reach workers, despite management’s disapproval. Even her children were brought into play. She recounted how she went to the docks to try to organise the dockers with her three-month-old baby on her back and leaflets tucked into her blanket.

‘No-one at the gate ever looked at me until one terrible day. Just as I got to the gates, Nosizwe started to scream. She shook all the blankets. The leaflets flew all over the place. The men at the gate came to see what these pamphlets were all about. They were very shocked. Those men thought I was an old woman, coming to do cleaning jobs. They refused to let me through the gates that day. And afterwards I was extra careful at the docks.’

It was a stratagem Zora used repeatedly, either sitting on the grass outside a factory, waiting for workers to come out at lunch time, or explaining that her child was ill, to gain access to the factory floor.

‘Once I was caught at the Dorman Long factory. I went in, as always, looking for my ‘husband’. I went to a room at the back. Then I started a meeting. Suddenly I noticed all the workers looking very hard behind me. I could see in their faces that they wanted to tell me something. The boss had got in quietly while I was talking. But he did not understand me because I was talking in Xhosa. So I said in English: “Not everyone has paid for the hats I knitted. I want my money now.” But the boss knew that I was lying…So he threw me out.’

At the heart of her approach was a determination to have workers themselves decide as much of the strategy as possible, and to be engaged in endorsing or rejecting what had been decided. An Advice Bureau manual, under the heading ‘Things to Remember’, instructed shop stewards instructed to: ‘Always consult the workers. Always report back to the workers.’ The work of the organisers and the support of the Advice Bureau paid off.

By 1975 there were committees at 40 factories and ‘a city-wide union in all but name’ had emerged. It was a small step to the founding of the General Workers Union in 1981. Between these two dates the unions went through extremely trying times. In 1976, coinciding with the Soweto uprising, the state engaged in an intense period of repression. Organisers, including Zora, were arrested and imprisoned for a period of four months. Some were killed.

Theory and Practice

The students and academics often engaged in theoretical debates, for which Zora had little time. As her obituary pointed out: ‘She was one of those tough, independent-minded Langa women. She was not an intellectual. In meetings, while the young students hotly debated the issues of the day, Zora would drop tolerantly off to sleep. But her instincts were built on a rock – the rock of workers’ rights. Many times ‘our young baby’ – that is what she called the growing organization – was threatened by the security police. She never wavered. Many times there were political and strategic challenges. Her answer was always “Workers first”. She had no time for any party line.’

Zora, interviewed about her relationship with whites made clear that their race made little difference, pointing out that her work in the ANC and SACTU had also been with whites. Zora insisted that workers themselves really appreciated the work of the white students who came to help them. She knew that some might be police agents sent to infiltrate the union movement, but that this was as likely to be undertaken by blacks as by whites.

Zora was a remarkable woman: absolutely incorruptible. She declined a car offered to her by the security police. As her obituary put it: “Zora never thought of herself. When she retired from the union, she did not become an industrial relations officer or a Memember of Parliament. She started a training project for unemployed workers. Zora made the workers the cause of her life.”

The High Price Paid

There is no official list commemorating what happened to them, but those connected with the Wages Commissions who were killed, jailed or banned include the following.

Died in detention: Elijah Loza and Storey Mazwembe (both of whom worked at the Western Province Workers’ Advice Bureau); assassinated: Rick Turner and Jeantte Curtis (the founders and inspiration behind the Wages Commissions).

Detained and banned: Zora Mehlomakulu, Paula Ensor, David Hemson, Johnny Copelyn, Jeremy Baskin, John Frankish, Judy Favish, Pat Horn, Gideon Cohen, Jack Lewis, Debbie Budlender, Willie Hofmeyr, Gavin Anderson, Sipho Kubekha, Jeanette Curtis, Jeannette Murphy, Mike Murphy, Elijah Loza, Chris Albertyn, David Davis, Halton Cheadle, Karel Tip and Charles Nupen.