Stretching across northern Nigeria and Niger, the Sokoto Caliphate was as ‘one of the largest slave societies in modern history,’ according to Mohammed Bashir Salau, who wrote, Plantation Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate: A historical and comparative study.

In the middle of the nineteenth century it extended more than 1,500 kilometres, from the mountains of Mandara, in present day Cameroon, to the city of Dori, in what is now Burkina Faso. The caliphate was one of several slave empires that were created by West African jihads in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Sokoto Caliphate

The Sokoto empire lasted for a century and was only finally extinguished when Britain conquered it in 1903. Outside of Nigeria the Caliphate is not generally recognised or understood, although regional domination and enslavement were at the heart of its existence.

Usman dan Fodio rose from Fulani scholar and preacher to respected religious leader. He emerged from a devout Islamic family to become an inspirational figure who launched the jihad that founded the Sokoto Caliphate in 1804. The Sokoto jihad was spearheaded by men who wanted a return to a pure form of Islam based on their understanding of seventh century Arabian cultural and religious practices.

Elected ‘Commander of the Faithful’ by his followers, Usman dan Fodio initiated his jihad. In a series of fierce battles, he succeeded in taking Gobir in 1808 and establishing the Caliphate the following year.

The Caliphate distributed land holdings to individuals and families, who in turn developed their estates to grow a wide variety of crops. The largest holdings went to the Fulani elite.

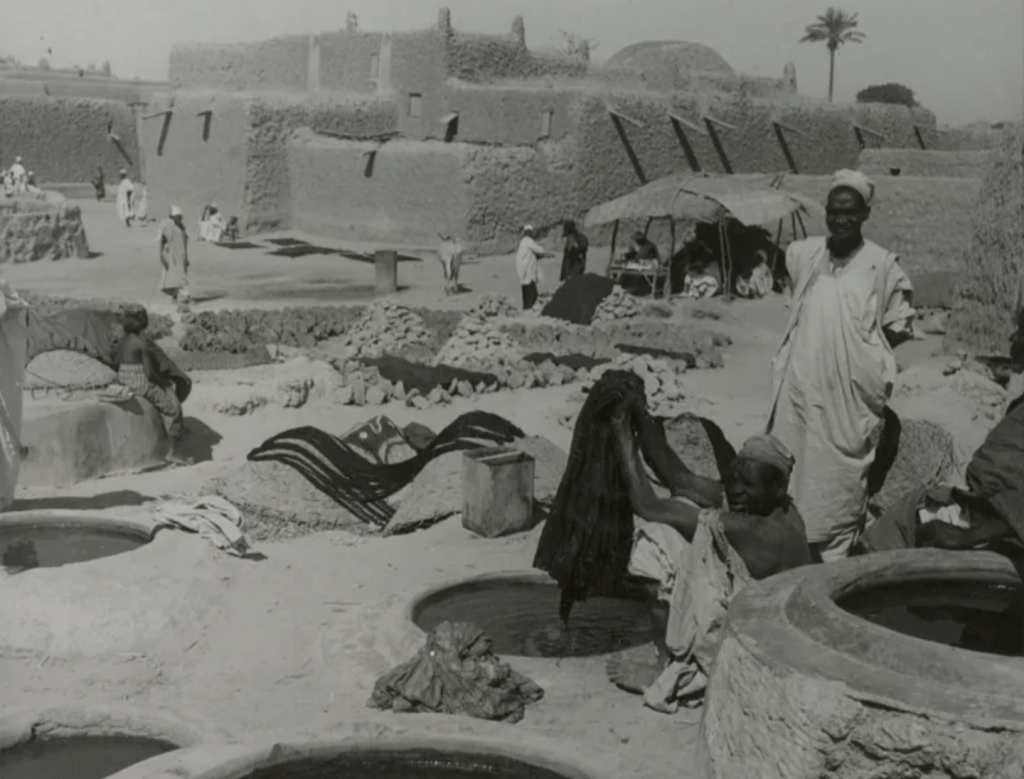

They cultivated cotton, indigo, millet and sorghum as well as irrigated crops such as rice, tobacco, onions, sugar cane and wheat. Their plantations produced kola and shea nuts. Cotton was dyed in pits. To work these Sokoto relied on vast numbers of slaves.

They were essential for every aspect of the Caliphate’s economic life, as well as serving in domestic households as servants or concubines.

As Professor Paul Lovejoy put it:

Caliphate military campaigns fed a steady stream of war captives into the economy, and this ready supply of slaves accounts for the relative stability of slave prices during the whole [nineteenth] century, with real prices perhaps even declining in the last third. The aristocracy retained many of these captives, but a well-developed commercial sector also transferred them to central markets.

The British Conquest

The British penetration of Nigeria’s interior was led by commercial interests which came together in the Royal Niger Company. However, following the Conference of Berlin (1884 – 1885) Africa was divided between the imperial powers, and Britain found itself competing with the French and Germans for control of West Africa.

By the end of the nineteenth century the British had pushed far up the Niger and began clashing with the Sokoto Caliphate. This culminated in 1903, when Sir Frederick Lugard finally conquered Sokoto. The West African Frontier Force, of just 21 officers and 500 troops, but armed with machine guns and artillery, defeated the caliph’s army of 2,000 cavalry and 6,000 infantry. For Sokoto the British victory was terminal.

‘When the sun set that day on the smoking ruins of Burmi, with the dead lying thick in the trenches, on the ramparts, and among the houses, the Fulani Empire came to an end.’ [Hugh A. S. Johnston. The Fulani Empire of Sokoto, op. cit. p. 257]

Lugard found he had inherited some 2 million slaves from the Caliphate, despite Britain having freed all its own slaves across its Empire in 1833, with the last being emancipated by 1838. It was to take a further 20 years for the last of the Sokoto slaves to be freed, despite the fact that many looked to Britain as their liberator.

‘A flag-touching dance,

Is performed by freeborns alone,

Anybody who touches the flag,

Becomes free,

He and his father [master], Become equals.’

Sokoto under British rule

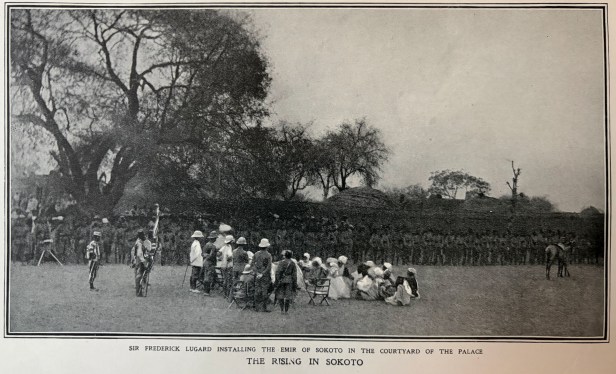

Few images exist of life under British rule, but this shows Lugard installing a new Emir of Sokoto in 1906.

The photograph, taken from The Graphic of 3 March 1906 is important. It shows the British on chairs while the Emir appears with his followers sitting on the ground in front of them. The image speaks for itself!

The accompanying story (for which the Graphic clearly had no contemporary photographs) was about the garrison of the Northern Nigeria Regiment supported by one company of mounted infantry having come under attack. “It would appear from the Lagos telegram that the whole of the latter has been wiped out, including three officers. The outbreak is said to be the work of a new Mahdi.”

In addition to the three British officers, 25 “native troops” had been killed. The British residence in Sokoto was said to be safe and “local chiefs are loyally co-operating in suppressing the rising” aided, no doubt, by the 150 troops that were being rushed to Sokoto to end the uprising.

Below is another photograph of the Northern Nigerian Regiment with British officers in less troubled times.

The rebellion was not long lived and Britain found other ways of controlling Sokoto.

London believed in a “hearts and minds” approach – bringing elites, including chiefs and Emirs to Britain so that they might see how troops were trained. The sub-text was that rebellion would be useless, since the Empire was so powerful.

Below if a photograph from 20 June 1934.

The photograph, by Acme of New York, has this description on the rear. “African chiefs witness British Tommies in Action. The three West African chiefs, the Sultan of Sokoto, interested spectators at a demonstration of machine gunning by British Soldiers at Ash Ranges, Aldershot. England.”

It is worth pointing out that by this time the chiefs were seated, with only their followers sitting on the ground!