Security failure is rarely sudden. It unfolds as a series of small collapses that become irreversible. South Africa faces two interacting risks: external capture and internal fracture.

By Joan Swart Defenceweb 18 December 2025

South Africa’s security environment is entering a decisive and dangerous phase, not because of a single event or adversary, but because the state itself is losing the structural capacity to govern, defend, and project stability.

The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) is increasingly expected to fulfil roles that no longer align with its resources, equipment, or institutional health. What results is not a stable state with a weakened military — it is a weakening state whose internal decay directly accelerates military and security collapse.

The common narrative is that South Africa aspires to high constitutional ideals but struggles to implement them. In reality, those ideals have become a form of political currency rather than a coherent national project. The language of rights, sovereignty, and rule of law is invoked when convenient but not backed by sustained investment, institutional discipline, or strategic foresight. As a result, sovereignty is becoming performative. And performative sovereignty is fragile.

The SANDF’s decline is well documented: chronic underfunding, ageing platforms, collapsing infrastructure at bases, a shrinking technical core, and low operational readiness. This trajectory was already recognised a decade ago in the Defence Review 2015, which explicitly warned of “critical decline” if funding and capability were not restored.

But this is only one layer of the crisis. The deeper problem is that South Africa is now too weak institutionally to sustain a modern military at all.

Electricity, water systems, ports, railways, and communication infrastructure — all essential to military readiness — are deteriorating faster than they can be repaired. The security cluster is riddled with corruption, factionalism, and unprofessional political interference. Intelligence structures have neither the cohesion nor the credibility to provide accurate warning, as exposed in the 2021 unrest. This was confirmed by the Expert Panel Report on the July 2021 Civil Unrest.

Armscor and Denel, once strategic assets, are sliding into irrelevance, and procurement has become riskier, more politically distorted, and less aligned with operational needs.

South Africa does not only have a struggling defence force. It has a defence force embedded in a failing state ecosystem. No amount of military reform can succeed inside a governance environment unable to maintain even the minimum conditions for defence capability.

Internal Stability at Risk: A State Losing Its Monopoly on Violence

Domestically, the state is steadily losing its monopoly on violence — the most basic requirement for sovereignty.

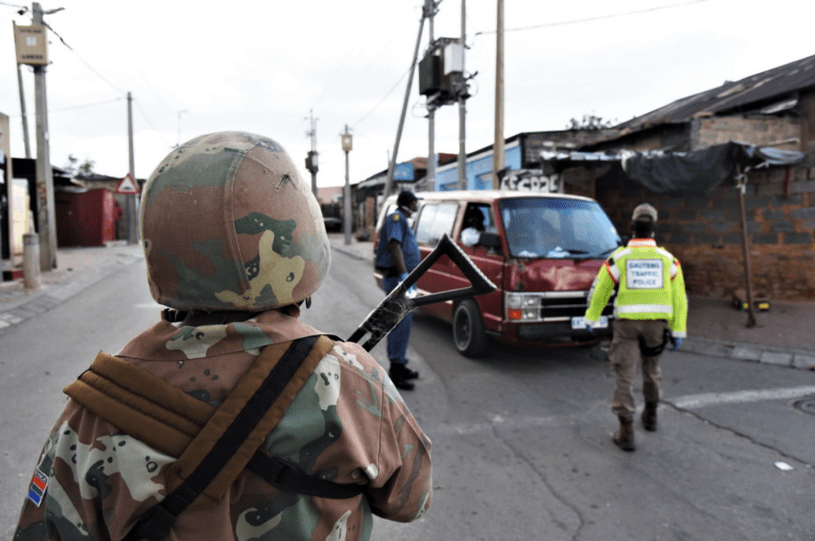

Organised crime syndicates, political militias, and gang-controlled zones exercise de facto authority in provinces like KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng, and the Western Cape. Critical infrastructure is routinely sabotaged or extorted without meaningful consequence.

Border security remains largely symbolic, with porous crossings exploited by smugglers, human-trafficking networks, and criminal groups. The Border Management Authority’s own reporting acknowledges persistent operational gaps and rising transnational crime.

The July 2021 riots were not an anomaly — they were a systems test, and the system failed. The state could not deploy intelligence, command structures, or rapid response forces with any coherence. It took days to restore basic order. The SANDF’s slow mobilisation and limited operational effect revealed the gap between mandate and capability.

South Africa is now in the phase where internal fragmentation becomes self-reinforcing: weakened state capacity allows alternative power centres to emerge, and those power centres further weaken the state.

This is how fracture begins.

External Actors Exploiting South Africa’s Vulnerabilities

As the state weakens, foreign powers move into the vacuum — not necessarily with hostile intent, but with opportunistic strategy. The result is rising external influence that erodes sovereignty from the edges inward.

China’s involvement in South Africa has shifted from commercial investment to strategic presence. The overhaul of the De Brug military facility and expanded cooperation agreements illustrate the deepening relationship. DefenceWeb has repeatedly reported on these developments, including concerns raised about the opaque nature of Sino–South African engagements.

Chinese contractors embedded in critical energy, port, and digital infrastructure create dependencies that South Africa is not structurally capable of managing. Beijing does not need coercion — dependency is its leverage.

Despite political rhetoric, South Africa remains economically and ideologically closer to the West than to any BRICS partner. The United States remains one of South Africa’s top trade partners, and AGOA access continues to underpin large export sectors. The U.S. government’s own trade data highlights this strategic interdependence.

But Washington’s foreign policy operates on leverage. It does not destabilise South Africa directly; instead, it uses existing fractures to influence outcomes: trade pressure, diplomatic signalling, security concerns around Russia, and narrative warfare on corruption and terrorism financing.

South Africa’s defence procurement history — from the 1999 Arms Deal to more recent opaque weapons transfers — continues to erode international confidence. The Zondo Commission laid bare how procurement distortions undermine state institutions.

Procurement misaligned with operational reality invites foreign intelligence penetration, misallocation of resources, and obligations to actors whose strategic aims diverge from South Africa’s own.

A State Ripe for Capture or Fracture

Security failure is rarely sudden. It unfolds as a series of small collapses that become irreversible. South Africa faces two interacting risks: external capture and internal fracture.

State capture is not only internal corruption — it is external influence over critical systems, political factions, infrastructure, ports, digital networks, and military partnerships. As dependency deepens, sovereignty erodes.

State fracture arises from internal incoherence: regional governance divergence, failing service delivery, collapsing infrastructure, rising violence, and declining public trust. When the state can no longer guarantee safety, essential services, or economic stability, regions and communities begin to decouple from national authority.

South Africa is exposed to both trajectories simultaneously. Few states survive such dual vulnerability without major reform or major rupture.

The SANDF’s Strategic Trap

The SANDF is expected to guarantee national sovereignty while being denied the basic conditions required to function: adequate funding, operational platforms, secure infrastructure, skilled personnel, and a competent security cluster. It is increasingly a symbolic defence force — expected to project authority it does not possess.

External actors, organised criminal networks, and internal political factions see this clearly, even if the public does not. South Africa has become a soft target not for invasion, but for coercive diplomacy, influence operations, infrastructure exploitation, intelligence manipulation, and strategic dependency.

The country risks losing sovereignty not through war, but through erosion.

Final Thoughts

This analysis is alarmist — because the situation justifies alarm.

South Africa’s strategic decline is neither abstract nor reversible through symbolic reforms. A defence force embedded in a failing state cannot secure sovereignty, maintain territorial integrity, or protect critical assets.

Every month of drift deepens dependency on foreign powers, accelerates internal fragmentation, and increases the cost of recovery.

If the country does not act, the fracture will come from within, and the capture will come from without.

The warning signs are already here.

Dr Joan Swart is a psychologist, author, researcher and director at the CapeXit non-profit organisation.

The defunding of the SANDF – a deep financial dive

Real defence spending has contracted by an estimated 10–15% over the period, meaning that even stable nominal budgets are delivering progressively fewer operational outputs…The SANDF’s backbone—its personnel—is maintained at great cost, yet everything that makes a defence force effective (training, equipment, vehicles, technology, ammunition, maintenance) is either volatile, shrinking, or collapsing.

By Clive Coetzee19 December 2025

Source: Defence Web

In the previous articles, I explored the current state of affairs within the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) and unpacked the broader economics of defence expenditure. In this piece, I turn the spotlight squarely onto the finances of the Department of Defence (DoD) itself. By interrogating the numbers, across budgets, expenditure patterns, and long-term allocations, we can identify the trends, shifts, anomalies, and underlying pressures that have shaped the SANDF’s financial trajectory. Understanding these financial dynamics is critical, as they reveal not only how the organisation has been systematically underfunded, but also the strategic implications of this decline for South Africa’s security posture, force readiness, and institutional sustainability.

The financial analysis in this article is grounded in official data sourced directly from the National Treasury, specifically the Estimates of National Expenditure (ENE) Pivot – 7-Year View and the Appropriation Bill datasets. These provide a consistent, transparent, and detailed picture of the Department of Defence’s budget trajectory over time. To support this work, National Treasury developed an interactive dashboard (below) that enables drill-down analysis to level-4 line items, allowing for precise tracking of expenditure and budget allocations from the 2021/22 financial year through to the 2027/28 medium-term horizon.

The combined evidence from the nominal expenditure table (Table 1) and the stability/volatility indicators in Table 2 presents a clear and diagnosable picture of an institution whose expenditure structure is becoming increasingly misaligned with operational requirements. Using average annual percentage change, median change, average percentage contribution, and coefficients of variation (CVs), we can identify which line items are driving cost pressures, which are unstable, and which are effectively collapsing.

Table 1: Nominal Expenditure by Item (R’000)

| Items | 2021/22 Audited outcome | 2022/23 Audited outcome | 2023/24 Audited outcome | 2024/25 Revised estimate | 2025/26 Budget | 2026/27 MTEF1 | 2027/28 MTEF2 |

| Administrative fees | 15603 | 21808 | 24693 | 17595 | 17759 | 18457 | 19821 |

| Advertising | 46668 | 10776 | 20148 | 83754 | 64806 | 65548 | 66880 |

| Agency and support/outsourced services | 774797 | 1037790 | 822967 | 832136 | 870001 | 895559 | 919649 |

| Audit costs: External | 65278 | 76943 | 83365 | 88731 | 93119 | 96879 | 94878 |

| Biological assets | 287 | 0 | 556 | 40 | 142 | 144 | 66 |

| Buildings | 416052 | 748281 | 494167 | 393582 | 394360 | 401968 | 431681 |

| Catering: Departmental activities | 13005 | 25869 | 26344 | 69935 | 80315 | 73988 | 77201 |

| Communication (G&S) | 91587 | 89597 | 85735 | 101444 | 108428 | 113457 | 116067 |

| Computer services | 754174 | 854889 | 735071 | 934593 | 1042602 | 1084389 | 1091262 |

| Consultants: Business and advisory services | 12941 | 19296 | 5579 | 20798 | 17515 | 18330 | 18229 |

| Consumable supplies | 153673 | 150250 | 145372 | 222312 | 207151 | 215497 | 221076 |

| Consumables: Stationery, printing and office supplies | 44447 | 41665 | 50729 | 72128 | 78763 | 82394 | 89080 |

| Contractors | 1215441 | 1377142 | 1180286 | 1872191 | 1619514 | 1758879 | 1785732 |

| Departmental agencies (non-business entities) | 1665991 | 2800160 | 3605308 | 3658159 | 2877755 | 2988765 | 3088137 |

| Entertainment | 805 | 1092 | 1946 | 2822 | 2854 | 2970 | 3059 |

| Fleet services (including government motor transport) | 108132 | 146786 | 131842 | 267082 | 234646 | 250457 | 269362 |

| Foreign governments and international organisations | 55493 | 133421 | 77628 | 0 | 487000 | 455000 | 421000 |

| Infrastructure and planning services | 4908 | 801 | 120 | 4667 | 3678 | 4120 | 4276 |

| Inventory: Clothing material and accessories | 65255 | 214734 | 68692 | 152062 | 163678 | 147552 | 158506 |

| Inventory: Farming supplies | 3042 | 1915 | 2945 | 5015 | 4195 | 4471 | 4754 |

| Inventory: Food and food supplies | 1413474 | 1537789 | 1644783 | 1645449 | 1598113 | 1697890 | 1640615 |

| Inventory: Fuel, oil and gas | 446347 | 647945 | 658732 | 876978 | 896058 | 921185 | 997615 |

| Inventory: Materials and supplies | 94861 | 151765 | 48648 | 127130 | 109614 | 118376 | 126550 |

| Inventory: Medical supplies | 415573 | 63996 | 57666 | 120413 | 129099 | 138420 | 146500 |

| Inventory: Medicine | 242818 | 219505 | 229116 | 253136 | 271134 | 292164 | 337417 |

| Inventory: Other supplies | 61515 | 25603 | 33529 | 76757 | 76846 | 79836 | 83040 |

| Laboratory services | 77099 | 78887 | 67644 | 59055 | 69692 | 72768 | 76967 |

| Legal services (G&S) | 18962 | 20879 | 28266 | 46153 | 48361 | 50466 | 54125 |

| Minor Assets | 63018 | 45476 | 67580 | 286075 | 235930 | 220329 | 237655 |

| Non-profit institutions | 7753 | 3446 | 4709 | 11932 | 10979 | 11418 | 11857 |

| Operating leases | 1381017 | 1966538 | 1342994 | 1582217 | 1221570 | 1291215 | 1347718 |

| Operating payments | 189047 | 573738 | 739785 | 702686 | 447170 | 481615 | 416281 |

| Other machinery and equipment | 382592 | 238500 | 401071 | 278758 | 300104 | 306186 | 358233 |

| Payments for financial assets | 3033886 | 3605086 | 4468 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Property payments | 1539990 | 1361846 | 1531984 | 2357035 | 2318539 | 2456188 | 2561664 |

| Rental and hiring | 5122 | 41330 | 25478 | 19798 | 5021 | 5274 | 5504 |

| Salaries and wages | 33701874 | 34660616 | 35307132 | 35148444 | 36703098 | 38421236 | 39940293 |

| Science and technological services | 70229 | 62905 | 39063 | 57688 | 65867 | 66586 | 67130 |

| Social benefits | 167661 | 1357290 | 2312197 | 244401 | 219785 | 249068 | 270346 |

| Software and other intangible assets | 49662 | 75941 | 24789 | 1532 | 2480 | 928 | 1093 |

| Specialised military assets | 0 | 0 | 5344 | 20981 | 20623 | 21886 | 22784 |

| Subsidies on products and production (pc) | 1480055 | 1478501 | 1446251 | 1399984 | 1464582 | 1531681 | 1600300 |

| Training and development | 186636 | 204731 | 125426 | 208931 | 233717 | 242851 | 253237 |

| Transport equipment | 180328 | 343697 | 159568 | 116304 | 91910 | 75542 | 70828 |

| Travel and subsistence | 1071883 | 1452898 | 1970219 | 1044892 | 1007317 | 1059812 | 1126480 |

| Venues and facilities | 10470 | 13223 | 16660 | 19901 | 24470 | 25779 | 26919 |

| Grand Total | 51823728 | 58211551 | 55861879 | 55506648 | 55940704 | 58517876 | 60662249 |

Source: National Treasury/Own Calculations

Table 2: Stability/volatility Indicators by Item (%)

| Items | AverageChange | MedianChange | CV Change | Average Contribution | Median Contribution | CV Contribution |

| Administrative fees | 5,22 | 5,66 | 4,23 | 0,03 | 0,03 | 0,15 |

| Advertising | 51,05 | 1,59 | 2,74 | 0,09 | 0,11 | 0,52 |

| Agency and support/outsourced services | 4,09 | 2,81 | 4,26 | 1,55 | 1,52 | 0,07 |

| Audit costs: External | 6,60 | 5,69 | 0,99 | 0,15 | 0,16 | 0,11 |

| Biological assets | 1,57 | -27,08 | 83,66 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 1,09 |

| Buildings | 5,84 | 1,06 | 6,76 | 0,83 | 0,71 | 0,26 |

| Catering: Departmental activities | 46,25 | 9,59 | 1,52 | 0,09 | 0,13 | 0,55 |

| Communication (G&S) | 4,28 | 3,47 | 1,88 | 0,18 | 0,18 | 0,10 |

| Computer services | 7,11 | 7,78 | 1,95 | 1,63 | 1,68 | 0,13 |

| Consultants: Business and advisory services | 39,85 | 2,05 | 3,02 | 0,03 | 0,03 | 0,31 |

| Consumable supplies | 7,88 | 0,18 | 2,85 | 0,33 | 0,36 | 0,18 |

| Consumables: Stationery, printing and office supplies | 13,27 | 8,66 | 1,26 | 0,12 | 0,13 | 0,27 |

| Contractors | 9,04 | 5,07 | 2,96 | 2,72 | 2,90 | 0,17 |

| Departmental agencies (non-business entities) | 14,02 | 3,59 | 2,20 | 5,20 | 5,11 | 0,22 |

| Entertainment | 27,84 | 19,86 | 1,11 | 0,00 | 0,01 | 0,41 |

| Fleet services (including government motor transport) | 21,71 | 7,14 | 1,99 | 0,35 | 0,42 | 0,33 |

| Foreign governments and international organisations | -2,57 | -7,02 | -30,87 | 0,40 | 0,23 | 0,90 |

| Infrastructure and planning services | 602,51 | -8,70 | 2,59 | 0,01 | 0,01 | 0,62 |

| Inventory: Clothing material and accessories | 47,94 | 7,53 | 2,25 | 0,24 | 0,26 | 0,37 |

| Inventory: Farming supplies | 13,93 | 6,45 | 2,94 | 0,01 | 0,01 | 0,29 |

| Inventory: Food and food supplies | 2,63 | 3,14 | 2,03 | 2,82 | 2,86 | 0,05 |

| Inventory: Fuel, oil and gas | 15,54 | 5,55 | 1,21 | 1,36 | 1,57 | 0,23 |

| Inventory: Materials and supplies | 25,75 | 7,45 | 3,04 | 0,20 | 0,20 | 0,28 |

| Inventory: Medical supplies | 5,77 | 6,53 | 10,70 | 0,28 | 0,23 | 0,86 |

| Inventory: Medicine | 5,94 | 7,43 | 1,43 | 0,46 | 0,47 | 0,13 |

| Inventory: Other supplies | 18,25 | 3,95 | 3,38 | 0,11 | 0,14 | 0,37 |

| Laboratory services | 0,59 | 3,37 | 20,54 | 0,13 | 0,12 | 0,10 |

| Legal services (G&S) | 20,86 | 8,68 | 1,14 | 0,07 | 0,08 | 0,37 |

| Minor Assets | 54,63 | 0,63 | 2,46 | 0,29 | 0,38 | 0,61 |

| Non-profit institutions | 22,39 | 3,92 | 3,16 | 0,02 | 0,02 | 0,39 |

| Operating leases | 2,63 | 5,04 | 10,27 | 2,56 | 2,40 | 0,17 |

| Operating payments | 30,87 | 1,34 | 2,83 | 0,89 | 0,82 | 0,37 |

| Other machinery and equipment | 4,45 | 4,84 | 8,55 | 0,57 | 0,54 | 0,21 |

| Payments for financial assets | -30,17 | 0,00 | -1,81 | 1,72 | 0,00 | 1,71 |

| Property payments | 10,56 | 5,12 | 2,15 | 3,55 | 4,14 | 0,23 |

| Rental and hiring | 96,84 | -8,97 | 3,10 | 0,03 | 0,01 | 0,91 |

| Salaries and wages | 2,89 | 3,40 | 0,67 | 64,03 | 65,03 | 0,04 |

| Science and technological services | 2,57 | 0,95 | 10,97 | 0,11 | 0,11 | 0,18 |

| Social benefits | 117,04 | 10,93 | 2,52 | 1,21 | 0,44 | 1,22 |

| Software and other intangible assets | -15,20 | -22,40 | -4,44 | 0,04 | 0,00 | 1,32 |

| Specialised military assets | 50,19 | 2,05 | 2,37 | 0,02 | 0,04 | 0,82 |

| Subsidies on products and production (pc) | 1,37 | 2,19 | 2,67 | 2,63 | 2,62 | 0,04 |

| Training and development | 9,60 | 6,99 | 3,50 | 0,37 | 0,38 | 0,19 |

| Transport equipment | -5,85 | -19,39 | -8,51 | 0,26 | 0,21 | 0,63 |

| Travel and subsistence | 5,35 | 5,75 | 5,70 | 2,21 | 1,88 | 0,29 |

| Venues and facilities | 17,41 | 21,21 | 0,58 | 0,03 | 0,04 | 0,30 |

| Grand Total | 2,78 | 2,22 | 2,01 | 100,00 | 100,00 | 0,00 |

Source: National Treasury/Own Calculations

The financial trajectory of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), as revealed through the nominal expenditure trends in Table 1 and the stability/volatility indicators in Table 2, paints the picture of a defence institution caught in a prolonged cycle of stagnation, structural imbalance, and quiet erosion. Over the seven-year period from 2021/22 to 2027/28, total defence spending grows at an average nominal rate of just 2.78% (median 2.22%), with a low coefficient of variation (CV) of 2.01 for year-on-year change. On the surface, this suggests stability; yet, once inflation is factored in—4.6% in 2021, 7.0% in 2022, 6.0% in 2023, 4.4% in 2024, and around 3% projected for 2025—the picture shifts dramatically. Real defence spending has contracted by an estimated 10–15% over the period, meaning that even stable nominal budgets are delivering progressively fewer operational outputs. With inflation assumed at approximately 4% in 2026 and 2027, the small MTEF increases barely stabilise purchasing power, let alone reverse the long-term decline.

At the core of this structural malaise is the overwhelming dominance of personnel-related expenditure. Salaries and wages absorb an average of 64.03% of the entire SANDF budget (median 65.03%), with a remarkably low CV for contribution (0.04), indicating a rigid and entrenched cost centre. Yet personnel spending grows at only 2.89% annually (median 3.40%), below inflation and barely above the total budget growth rate—meaning real wages for soldiers and officers are stagnating or shrinking. Social benefits add further pressure. Although they average a staggering 117% annual change (with a volatile CV of 2.52), this is driven by erratic spikes—such as the explosion from R167 million in 2021/22 to R2.31 billion in 2023/24—likely linked to early retirements, pension obligations, or severance as force levels shrink. The combination of these two items reflects a classic “wage bill trap”: personnel costs are essential and politically immovable, yet their size—consuming more than 65 cents of every rand—crowds out funding for training, maintenance, equipment renewal, and operational readiness.

Other expenditure items show clear signs of stress, often reflecting external cost drivers such as energy prices or the growing reliance on outsourcing. Inventory: Fuel, oil, and gas grows by an average of 15.54% per year (median 5.55%, CV 1.21) as global energy volatility pushes the item from R446 million to nearly R1 billion by 2027/28. Contractors (9.04% average change, CV 2.96) and property payments (10.56%, CV 2.15) both contribute meaningful shares—2.72% and 3.55% respectively—indicating the SANDF’s increasing dependence on external providers to maintain basic operational and support functions. Transfers to departmental agencies (non-business entities), averaging 14.02% growth and contributing 5.20%, spike sharply in certain years—such as the R3.6 billion in 2023/24—likely reflecting procurement cycles or Armscor-related support. These items underscore a defence system that is increasingly reactive to market forces rather than strategically guided by long-term force design.

The volatility in several categories highlights deeper instability that complicates planning and weakens readiness. Biological assets—though small—show extreme variability (CV 83.66), swinging unpredictably between expenditure and zero. Far more concerning, medical supplies (CV 10.70) collapse from R416 million in 2021/22 to R58 million in 2023/24 before partially recovering. Operating leases (CV 10.27) and transfers to foreign governments and international organisations (CV -30.87) also fluctuate wildly, with the latter reflecting inconsistent funding for peacekeeping obligations. These swings create fiscal whiplash, making it difficult to sustain health readiness, logistics, and international commitments.

Most concerning is the unmistakable decline in capital renewal and modernization. Transport equipment shrinks by an average of -5.85% per year (median -19.39%), dropping from R180 million to just R71 million—a clear sign of deferred maintenance and stalled fleet replacement. Software and intangible assets, essential for modern command-and-control and cybersecurity capacity, decline by -15.20% annually, falling from R50 million to less than R1 million. Payments for financial assets fall to zero after 2023/24, removing what little fiscal buffer the system had for once-off adjustments. Collectively, these declines constitute a hollowing-out of capability: the organisation retains personnel but loses the tools, technology, and mobility required to function as a modern defence force.

Taken together, the expenditure profile reveals a defence force whose budget is profoundly misaligned with its operational mandate. The SANDF’s backbone—its personnel—is maintained at great cost, yet everything that makes a defence force effective (training, equipment, vehicles, technology, ammunition, maintenance) is either volatile, shrinking, or collapsing. Training itself grows at 9.60% on average, but its share is a negligible 0.37%, far too low to sustain proficiency across the services. The result is an institution increasingly unable to fulfil domestic or regional missions despite nominally “stable” funding.

The financial analysis reveals a department caught in a structural whirlpool—reactive, constrained, and increasingly unable to align its spending with its strategic mandate. Addressing this trajectory will require a deliberate and coordinated effort to restructure and revitalise the organisation, ensuring it can adapt to persistent fiscal pressures while rebuilding capability and long-term sustainability.

While the current and previous articles have focused on the financial and economic dimensions of the SANDF, the next set of articles will shift attention to the human capital side of the organisation. This upcoming series will examine personnel numbers, staffing trends, and the full cost of maintaining the SANDF workforce, providing a deeper understanding of how employee-related pressures shape the broader defence trajectory.

Dr Clive Coetzee is Department of Economics & Defence Organisation and Resource Management School Chair under the Faculty of Military Science at Stellenbosch University.