Unbroken Chains: Baroness Hayter finds Martin Plaut’s examination of 5,000 years of African enslavement both chilling and enlightening.

Without minimising Europe’s shameful role, this chilling book exposes the extent of the historic slave trade within Africa and across the Middle East

The House

By Martin Plaut Publisher Hurst & Co

12 Jan 2026

This extraordinary, uncomfortable book on the dismal history of the trade in human souls opens with a 1781 quote from Elizabeth Freeman (a telling surname) vouching that, when she was enslaved, she would have given her whole life for just one minute as a free woman on God’s earth.

No more chilling reminder is needed of the psychological as well as physical toll of this subjugation.

But this is not the book House readers might expect. It is not about the Caribbean and Americas and our own shameful role. Rather, it describes how slavery wasn’t invented by the West, nor in the 19th century.

Martin Plaut’s childhood in Cape Town was surrounded by descendants of slaves who had never left the continent. His detailed sources evidence that slavery wasn’t imposed from outside Africa, can’t be conflated with colonialism and was far more extensive than the transatlantic trade later introduced by the Portuguese and then other Europeans.

Between 650 AD and 1900, 40 million Africans were enslaved – not simply at the hands of foreign powers. Africans themselves engaged in this terrible trade centuries before any international intervention, with enslavement beginning on the banks of the Nile.

Even after Europeans became the exploiters, they depended on coastal Africans to capture and supply the men and women from the interior. And while the European slave trade lasted several hundred years, intra-Africa slavery lasted over 5,000 years. Indeed, at the time of the American civil war in the 1860s, the Sokoto Caliphate alone had a slave population equivalent to that of the USA.

Trade across the Indian Ocean was as significant as that across the Atlantic, lasted longer, and the scale was at least as great as that to the Americas and the Caribbean (perhaps 12.6 million over 11 centuries in the former; 11.3 million over 400 years in the latter).

During the 19th century, 115,000 east Africans were taken to Iran, with a similar number to Arabia. The rulers of Madagascar became enormously wealthy from enslavement until the 1820s, which was also widespread in the Ottoman Empire – with perhaps 1.2 million Africans making up to one-fifth of its population in the 16th century.

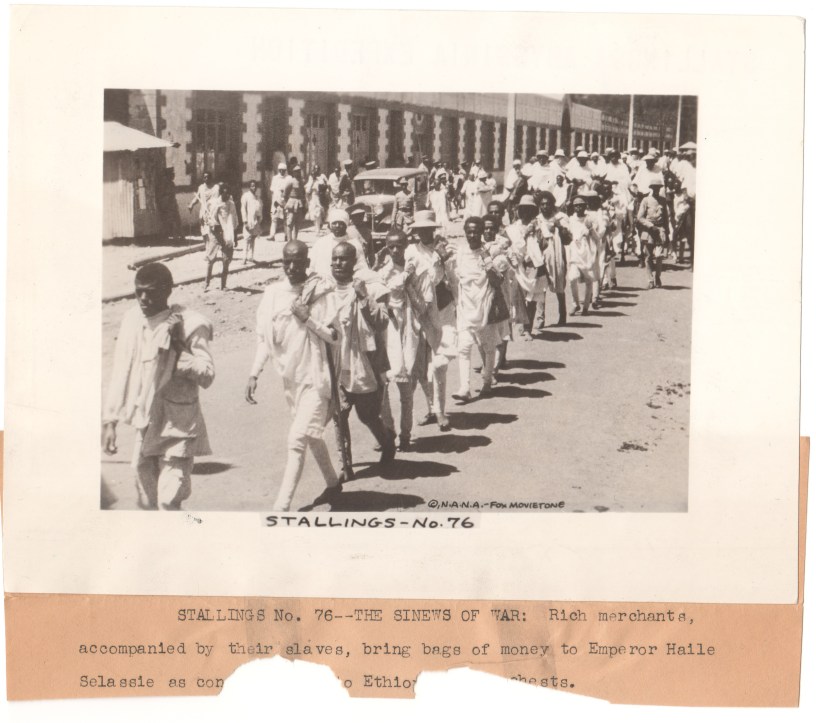

Oman enslaved people from deep within Africa in the clove plantations of Zanzibar (up to 100,000 by the 1830s), with the country playing such a large role that Plaut suggests it made the greatest impact on the history of slavery as the trade became a cornerstone of the Oman’s existence.

What happened within Africa long preceded the transatlantic trade, with forced movement across the Sahara, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean before European involvement. It is neither discussed nor acknowledged by the individual countries, or by the African Union and the Arab League.

International agencies exhibit the same reluctance. Unecso’s ‘Slave Route’ project only examines the transatlantic trade, and neglects to acknowledge the trans-Sahara route where 14 million sub-Saharan captives were made to trek to the Islamic world from the seventh to the 20th century. Millions died en route, and the survivors were forced to work in agriculture, the army, housework or as sex slaves – some sold to Oman, Persia, India and beyond.

Plaut believes that we should all face the horrors that were wrought on millions but that the stony silence of one part of the world needs to end. His uncomfortable book is one contribution to that debate. It will be attacked either for whitewashing our own role in slavery (which it doesn’t) or for stirring up unwelcome memories. But for historians, that should never be a reason for silence.

No, Europeans didn’t invent African slavery

By Pat Murphy | Jan 13, 2026

African slavery long predates European involvement, according to a new book

Title: Unbroken Chains: A 5,000-Year History of African Enslavement

Author: Martin Plaut

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Publication Year: 2025

(Available from Amazon)

As far as many people are concerned, African slavery is synonymous with the moral cataclysm of the Transatlantic slave trade, where Europeans shipped millions of unfortunate Africans to the Americas, both north and south. It was an undeniably brutal process.

Still, Martin Plaut’s Unbroken Chains: A 5,000-Year History of African Enslavement reminds us that “it’s only a fragment of the story.” Slavery in Africa goes back much further than that. And much of it had nothing to do with Europeans.

Four main themes struck me:

• The pervasiveness of African slavery before the Europeans;

• The fact that the Transatlantic slave trade was effectively a business partnership between Europeans and Africans;

• The contrasting roles of the two main European players—the Portuguese and the British;

• The mistaken conflation of Transatlantic slavery with European colonization of Africa.

Before the Europeans

Plaut ascribes the earliest evidence of African slavery to a stone carving from circa 2900 BCE. It’s to be found at the second cataract of the Nile and depicts a boat “packed with Nubian captives for enslavement in Egypt.”

Indeed, slave trading prevailed across the continent for centuries, involving all sorts of indigenous participants. For example, Ethiopia “used slaves from the earliest times.” If you were strong, you preyed on the weak.

And the sorry business wasn’t necessarily confined within Africa’s geographical boundaries, the Indian Ocean trade being a prime example. Initiated by Arab and Indian traders and later joined by Europeans, the practice extended over a much longer time period than the Transatlantic trade and cumulatively exported more slaves.

Plaut takes note of the arguments that slave systems weren’t always equally harsh. And, on balance, plantation slavery in the Americas was harder than what was practised in Africa.

But that doesn’t imply that the African method was benign. To quote an old saying among the Akan people of Ghana: “A slave’s life is in his master’s hand.”

And in Plaut’s reckoning, it was all “still slavery.”

Partnership

African American historian Henry Gates Jr. put it succinctly: “Erasing the role of black agents in the slave trade. That’s just dishonest. It’s bad history.” Nonetheless, it happens all the time.

European slave traders mostly bought their slaves from Africans and then shipped them across the Atlantic. After initial capture (by Africans), slaves were sometimes marched to the sea over vast distances before coming into European hands.

But why would Africans sell other Africans to Europeans?

In Atlantic Cataclysm, slavery historian David Eltis asks the question, and his answer is that, prior to the 20th century, there was no sense of a pan-African identity: “Africans sold other Africans because they did not know they were African.”

Put another way, the conception of one’s identity was much narrower than “being African.” It was more a matter of what ethnic group or tribe you belonged to. Prisoners taken in war and people deemed to be outsiders were excellent candidates for enslavement. In fact, wars were sometimes launched for the explicit purpose of accumulating human inventory.

The Portuguese and the British

While they were certainly major players, the British didn’t initiate the Transatlantic slave trade. That dubious distinction belongs to the Portuguese, who got into the business in the 1400s. They were also the largest European participant over the whole period.

That said, there was a span of roughly 75 years when British involvement surpassed that of the Portuguese. However, the situation changed dramatically in the 19th century.

First, the 1807 Slave Trade Act banned future slave trading across the British Empire. Then the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act tackled existing slavery, ending it in most British colonies and freeing more than 800,000 slaves in the process. And starting in 1808, the Royal Navy had begun interdicting slave ships departing from Africa. It was a process that cost the lives of some 17,000 British sailors over a 52-year period—a ratio of one sailor for every nine freed slaves.

To quote Plaut: “This was in stark contrast to the role of other slave traders, including the Arabs, the Ethiopians or the rulers of North Africa, whose routes across the Sahara continued to extract the slaves they desired.”

Slavery and colonialism

There is an argument that Transatlantic slavery was enabled by European colonization of Africa. This gets chronology the wrong way round.

Colonization requires control over territory and, when the Transatlantic trade took off in the 1700s, the physical European presence was mostly confined to coastal areas. As late as 1870, only 10 per cent of Africa was under European control, a figure which grew to 90 per cent between then and 1914. But by that time—when extensive colonization became feasible—the Transatlantic slave trade had died out.

Summing up

Of course, none of this renders the history of Transatlantic slavery any less reprehensible. But it would be useful, not to mention honest, to include all of the participants in our understanding of what happened.

And if we insist on a historical moral reckoning, we should look at the totality of African slavery rather than just the Transatlantic dimension. There should be no free passes.

Unsurprisingly, there seems to be little appetite for that.

Our Verdict: ★★★★☆

Unbroken Chains strips away the comforting myth that African slavery began and ended with Europeans. Author Martin Plaut traces a far older, continent-wide system of enslavement involving African, Arab and European actors, forcing a reckoning with history as it actually happened. His book is rigorous, unsparing and deeply uncomfortable—exactly what an honest account should be.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

Explore more on History books, Slavery, Colonialism, Human Rights

The views, opinions, and positions expressed by our columnists and contributors are solely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of our publication.

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country.

Congratulations — again! — Martin. Very gratifying, for sure!

John