By Ngala Chome

January 21, 2026

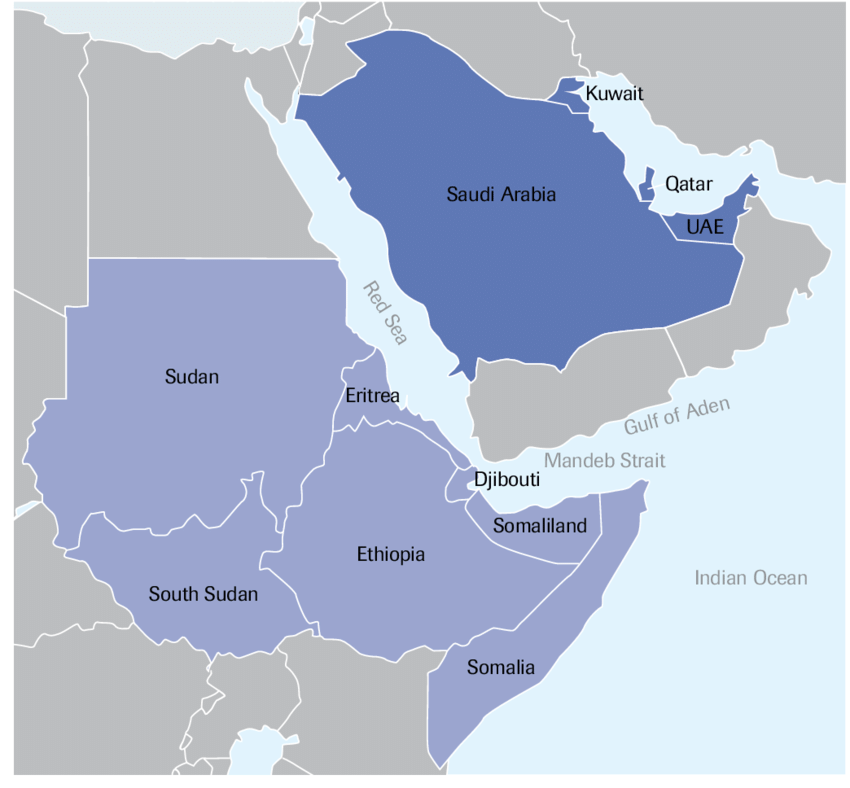

Map of the Gulf and the Horn of Africa

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland continues to reverberate across the Red Sea’s fast-changing geopolitics. How to read the emerging regional map? Certainly not through the lens of colonial cartographies.

The Horn of Africa continues to grapple with the consequences of Israel’s recognition of Somaliland on December 26, 2025 – a region Somalia maintains is part of its sovereign territory. But this recent Israeli pivot towards Somaliland follows a period of heightened regional tension that had escalated in early 2024 following Ethiopia’s reported intention to grant Somaliland diplomatic recognition in exchange for a naval base on the Gulf of Aden.

That incident triggered a tide of Somali nationalism, leading Mogadishu to rally regional allies against Ethiopia and demand the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops from Somalia – much like Mogadishu has now rejected Tel Aviv’s recognition of Hargeisa, and consequently expelled the United Arab Emirates (UAE) from Mogadishu.

Tensions in the region escalated when Egypt, currently in a dispute with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, entered a security pact with Eritrea and Somalia. As part of this alliance, Egypt pledged military personnel and arms to Somalia. In response, Ethiopia increased its military presence along the Ogaden border with Somalia, and encouraged insurgencies inside both Eritrea and Djibouti.

In April 2025, during a visit to Djibouti, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi reiterated that only littoral states should govern the Red Sea, a stance that effectively excludes Ethiopia. Simultaneously, Ethiopia’s ambitions for sea access shifted toward the Eritrean port of Assab after a Turkish-brokered rapprochement between Ethiopia and Somalia in late 2024 led Ethiopia to withdraw its deal with Somaliland. This has further strained relations with Asmara, despite their period of cooperation during the 2020–22 Ethiopian civil war.

For Ethiopia, the loss of access to the Red Sea has elicited a sense of nationalistic nostalgia for the period when Eritrea was part of the country, specifically regarding ownership of the ports of Assab and Massawa. For Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali, who is currently facing numerous insurrections, the issue of sea access serves as a catalyst for jingoism to redirect nationalist passions.

In contrast, Israel’s entry into the Horn of Africa’s geopolitical theatre has far more recent origins, and is motivated by events that followed the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack on its soil. This crisis led the Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen to launch missiles targeting Israel and disrupt international shipping in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Israel’s involvement also reflects the significant rupture between Saudi Arabia and the UAE, that now promises to recalibrate alliances across regional capitals throughout the wider Horn of Africa.

Integrating the Horn and the Gulf

The Horn of Africa is now being integrated into the security systems of the Indo-Pacific, the Mediterranean, and the wider Middle East. Indeed, the geopolitical competition for control along the Red Sea – around which the devastating wars in Yemen and then Sudan were forged – intensified significantly following the events in Israel of October 7.

The subsequent expansion of the Israel-Hamas conflict, which came to involve the Houthis in western Yemen, threatened to further destabilize not only the Middle East and the Gulf, but also the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden along the Horn of Africa coastline. This instability posed a severe threat to international merchant shipping and global oil transit.

Given that over 10 percent of global trade passes through the Bab-al-Mandab and the Suez Canal annually, these developments have come to underscore the critical geostrategic integration of the Horn of Africa and the Gulf region.

While analysts and foreign missions often view the Horn of Africa and the Gulf as separate portfolios, these two regions are increasingly forming a new geopolitical confluence. Separated by as little as 60 kilometres across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, the colonial, cultural, religious, and kinship ties between the former Ottoman Empire and the Horn of Africa remain significant.

These connections should not be overlooked or obscured by modern readings of the Muslim world that prioritize European colonial cartography. Today, consequential networks of influence are being built across the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, shaping new power configurations.

And while this integration is driven primarily by intensifying competition for influence over the Red Sea’s trade and transit routes, it is also being shaped by competing political visions for the future of the Muslim world, specifically between various forms of Islamism and their detractors.

This state of affairs could be traced to the geopolitical shifts following the 2011 Arab Spring, which saw traditional Middle Eastern powers such as Syria, Libya, Egypt, and Iraq eclipsed by the rise of Gulf states as the primary regional powerhouses. And they have not only been courted by traditional global powers (the USA, China, Europe and Russia) for their loyalty; they have been negotiating increasingly central roles as collaborators and strategic partners. Consequently, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE came to assume prominent roles in the mediation of the Israel-Hamas conflict, though their differing agendas contributed to an unstable ceasefire.

In fact, significant diplomatic divisions had persisted among these states, especially following the 2017 Saudi-Emirati-led blockade of Qatar. The UAE, for example, has remained the only one of the three Gulf states to have signed the 2020 Donald Trump sponsored ‘Abraham Accords’ that seek normalization of relations between Arab-Muslim states and Israel. Furthermore, varying levels of commitment to countering Islamist causes and differing diplomatic stances toward Iran – the leader of the ‘Axis of Resistance’ involving Hezbollah, the Houthi Movement, and Hamas – shaped mutual suspicions.

These rifts underscore the fragility of the diplomatic framework surrounding the crisis in Gaza, as seen in the Israeli attack on Hamas negotiators in Doha on September 9, 2025. Shortly after this incident, Saudi Arabia signed a defence pact with Pakistan – a nuclear power and a growing defence-industrial player in the Muslim world – offering protections similar to those of the NATO alliance.

Unconfirmed reports suggest that Turkiye and Egypt, but also Malaysia, Somalia, Indonesia, and Azerbaijan are considering joining this security arrangement. Analysts refer to the potential multilateral defence alliance as the new ‘Muslim-NATO’.

Recognizing Somaliland and its implications for the Horn

The outcome is that Israel has formed a security alliance with the UAE, and has gravitated toward the Emirati-led, but fragile ‘Axis of secessionists’. This refers to the UAE’s geopolitical strategy of supporting non-state and separatist actors across the Middle East, the Southern Arabian periphery, and the Horn of Africa. While this approach provides the UAE with strategic depth, it frequently places Abu Dhabi in opposition to central governments and regional rivals such as Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Notably, prior to recognizing Somaliland, Israel had signalled acceptance of the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) in Yemen. This relationship initially emboldened the STC to pursue an expansionist agenda, seizing oil-rich areas in Hadhramaut and al-Mahra near the Saudi border, which caused significant concern in Riyadh. Although Riyadh has since moved to reclaim these areas and the STC has been dissolved following the withdrawal of UAE security personnel, the resulting rift between the UAE and Saudi Arabia remains profound.

The Saudi Arabia and UAE rupture in Yemen not only parallels the civil war in Sudan, when both countries elected to support opposing sides of the ongoing civil war; their face-off is now sending ripples throughout the Horn of Africa.

It is notable that the Egyptian-led ‘Tripartite Alliance’ against Ethiopia’s ambitions for sea access originally included countries that have since aligned with states traditionally opposed to Israel. These include Iran, which is known to have developed relations with Asmara; Turkiye and Qatar, both of which remain strong allies of Mogadishu; and Saudi Arabia, which, together with Egypt, supports the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) in Khartoum. The SAF itself enjoys positive relations with Somalia, Eritrea and Egypt, i.e., the three signatories of the 2024 alliance of littoral states against Ethiopia.

While the UAE (which allies itself with Addis Ababa) has closed ranks with Israel in their support of Somaliland, Abu Dhabi continues its support of other separatist causes in the region, from Puntland to Jubaland in Somalia, the Libyan National Army in Eastern Libya, to Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Nowhere were these recalibrations of regional alliances in the Horn clearer than during the recent inauguration of Somalia’s newest federal member state, North Eastern State (NES) under Abdikhadir Ahmed Aw-Ali Firdhiye in Laas Aanood. The 16 January event inside a little-known location of Northern Somalia’s arid terrain was attended not only by Somalia’s President, Hassan Sheikh Mahmoud but also ambassadors from Saudi Arabia, Turkiye, China, Sudan, Djibouti and the Sudan Armed Forces, a loose alliance of countries that are opposed to Israel’s recognition of Somaliland on one level, and are against any possibilities of an Israeli military outpost along the Gulf of Aden on another.

The possibility of a proxy, or live conflict along the Gulf of Aden has never been more imminent. Days after Israel’s recognition of Somaliland – believed to have included amongst other agreements, the establishment of an Israeli outpost at the Somaliland port of Berbera – another agreement was hammered out between Mogadishu and Ankara for the establishment of a Turkish military base at Laas Qoray, a territory on the Somaliland coast outside Hargeisa’s control. Berbera and Laas Qoray lie only 357 kilometres apart.

These recent developments depict the geopolitical competition for influence and resources that has been taking shape along the Horn of Africa over the last decade, encompassing significant deposits of hydrocarbons, minerals, agricultural land, and strategic access to vital waterways and ports. Beyond material factors, it is important not to overlook the deeper ideological contest regarding competing visions for the future of the Muslim world. Put differently, this is also a contest between Islamist visions – represented principally by Iran, but also Qatar and groups like the SAF – and their detractors, most notably the emerging alliance between Tel Aviv and Abu Dhabi.

In sum, the emergence of middle powers on the global stage, particularly Gulf states, in the context of increasing global multipolarity, has become the major destabilizing factor in the Horn of Africa, leaving it in a state of flux and transition. More than ever before, these contestations, as they straddle the Horn and the Gulf, are bringing to life a new geopolitical confluence, with major consequences for the immediate future of the region and beyond.