For the second time in a matter of months the South African armed forces have defied President Ramaphosa – both times over ties with Iran.

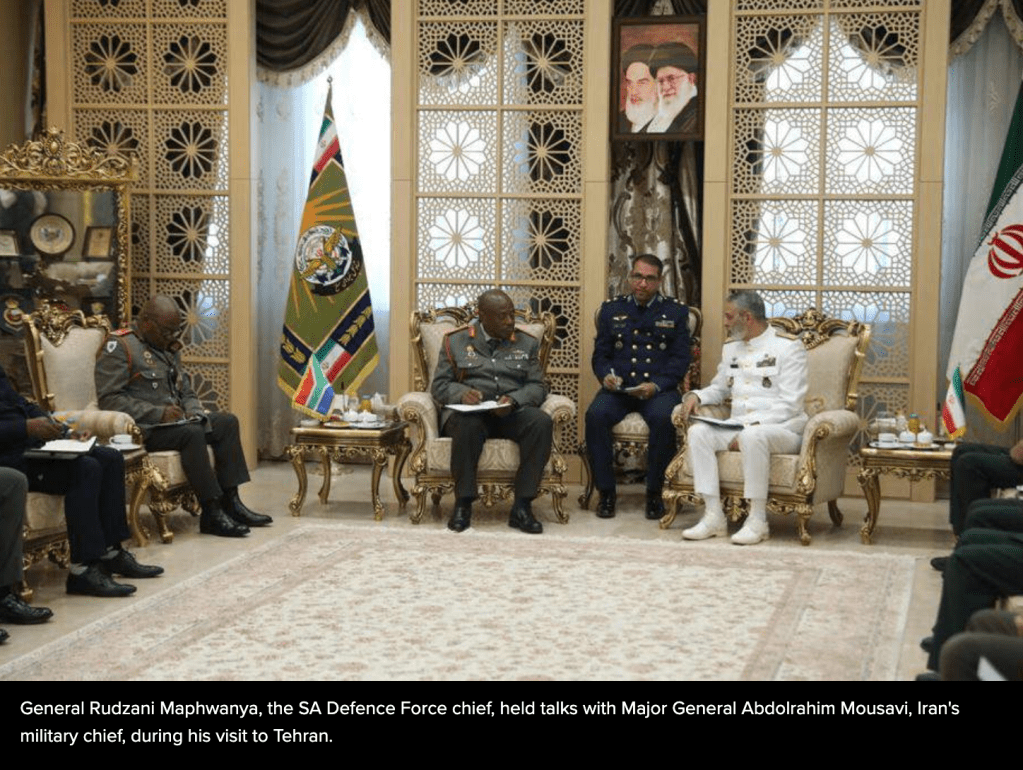

The first instance was in August 2025. Then President Cyril Ramaphosa had to admit that he did not know of or approve SANDF chief General Rudzani Maphwanya’s controversial visit to Iran.

Presidential spokesperson Vincent Magwenya described South African National Defence Force chief General Rudzani Maphwanya’s visit and his remarks “were not helpful…” when SA was “managing a very delicate exercise of resetting diplomatic relations with the United States” and negotiating a mutually-beneficial trade relationship… It is not helpful at all.”

This was the third official rebuke Maphwanya received in two days after International Relations and Cooperation Minister Ronald Lamola and Defence and Military Veterans Minister Angie Motshekga blasted him on Wednesday. Motshekga’s office said she would be “engaging with” him on his return from Iran.

Magwenya said Ramaphosa had not known of or sanctioned Maphwanya’s visit to Iran. That sort of travel approval “starts and ends with the minister (of defence and military veterans),” he said.

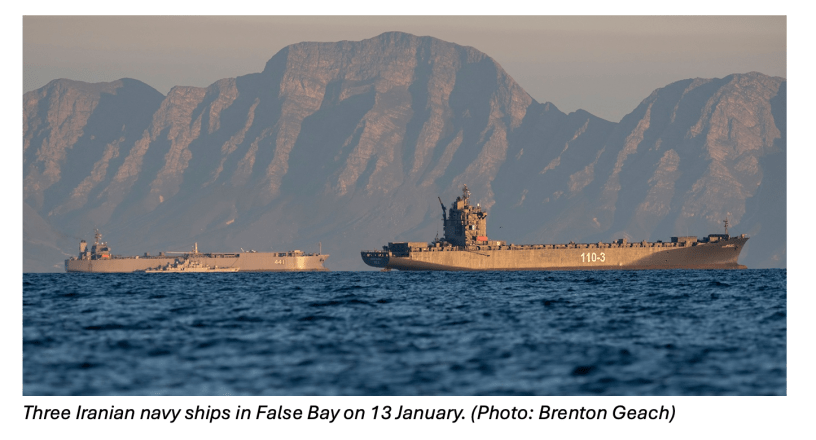

The January 2026 Iranian naval visit

Earlier this month warships flying Chinese, Iranian and Russian flags have been seen sailing into South Africa’s main naval base in Simon’s Town on the Cape Peninsula.

This was in direct defiance of the government. As News 24 reported: “Military chiefs blatantly defied Ramaphosa’s order to exclude Iran from naval exercises since November.”

The military and navy were given orders almost three months ago that Iran must under no circumstances participate in the recent naval exercise near Cape Town. The instruction was apparently repeated on various occasions in the weeks thereafter, but in an act of “blatant defiance”, no heed was paid to it.

According to two senior government sources, the first order was given early in November at an interdepartmental meeting. The instruction made it clear that Iran must not be involved as a participant or even as an observer in the Chinese-led Will for Peace naval exercise at Simon’s Town.

The presidency, the department of international relations and cooperation and the department of defence were present at the meeting.

They [the chiefs of the navy and military] were instructed as early as November that the Iranians must not participate in any way whatsoever. It was repeated in December, and again repeatedly in the week before the exercise took place.

“The four naval vessels forming part of the exercise consist of the United Arab Emirates corvette, Bani Yas, Russian corvette, Stoikiy, South African frigate, SAS Amatola, Iranian corvette, Naghi and Chinese destroyer, Tangshan,” the SANDF said, counting four ships, but actually listing five.

Mysteriously, this notice was later deleted from the SANDF’s Facebook page. The question that arises is what these military chiefs got from Iran in return for their defiance of the government.

Clearly, the South African military take little or any notice of what President Ramaphosa or the South African government instructs them to do. In other circumstances this would be labeled a mutiny.

This has only taken place once before in South African history, when General Botha led the country into the First World War in support of Britain and its allies. The Maritz Rebellion, as it was known was ended in four months, although it cost hundreds of lives. Where is the current military defiance taking South Africa?

Financial Mail

EDITORIAL: The perils of a disjointed government

The Iran naval embarrassment leaves South Africans wondering once again: who’s in charge?

January 22, 2026 at 05:00 amShare current article via EmailShare current article via FacebookShare current article via TwitterShare current article via LinkedIn

Civil authority over the military is deeply entrenched in most democracies, legally and by custom. It has a long tradition in South Africa, which is why the confusion over the failure last week to prevent Iranian participation in joint naval exercises off the Western Cape coast is so astonishing.

What seems clear is that President Cyril Ramaphosa ordered the withdrawal of Iran, and that the order was not obeyed. After that it gets murky. Did defence minister Angie Motshekga fail to pass on the order? Who did she pass it to? Was the order conveyed but not understood? Was it written down? Did someone in the chain of command choose to ignore it?

Intentional insubordination, by an individual or a group, seems highly unlikely, because in this case it would be so obvious and easy to detect. Disobedience of a lawful command is a criminal offence, and wilful disobedience can result in imprisonment, fines and dismissal from the force. Active rebellion would be extremely stupid.

Yet Motshekga has said that the president’s instructions were “clearly communicated to all parties concerned, agreed upon and to be implemented and adhered to as such”. Do these “parties” include the other navies, and not the senior defence force admirals and generals?

A panel was appointed to report in seven days what happened. It should not take even that long to discover where the order ran aground after it left the presidency.

Whatever the reason, one suspects gross incompetence somewhere.

Whatever emerges from the inquiry into the Iran naval embarrassment, somebody must take political responsibility

No less disturbing is the impression that the department of defence has been working independently of its international relations counterpart when it plans such exercises. Such an arrangement might almost have been designed to undermine the national interest, raising the spectre of a rogue military.

All this speaks again to a government that is not joined up. There appears to be no co-ordination between ministries, yet this is a fundamental principle of how cabinet government should work. Administration of a country is an endless option of difficulties, where priorities have to be identified and compromises hammered out. Yet the style of all ANC presidents has mainly been to appoint ministers and let them do their own thing.

Motor industry policy is undermined by inappropriate taxes. British American Tobacco is considering closing its manufacturing operation because the government has failed to deal with the scourge of illicit cigarettes. Smelters and steel plants close because protectionist measures are not thought through and electricity tariffs are a blunt instrument. Transnet closes branch railway lines when the country is crying out for revenue from rail tourism. Amid the confusing thickets of often conflicting legislation and regulation, it is the law of unintended consequences that reigns supreme.

Whatever emerges from the inquiry into the Iran naval embarrassment, somebody must take political responsibility — that is the minister. And one or more of the top defence bureaucrats, generals and admirals must take professional responsibility.

The president has to fire people. If he does not, he will have revealed he is not in command.

Who Is Really in Charge in South Africa?

Iran’s inclusion in a BRICS naval exercise reveals a civil-military relations problem in Pretoria.

By experts and staff

Published January 26, 2026 11:15 a.m.

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

Earlier this month, several members of the BRICS grouping conducted joint naval exercises, called “Will for Peace 2026” off South African waters. China led the training, participating alongside their South African hosts, Russia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates. South Africa’s enthusiasm for BRICS is not new. The somewhat inchoate grouping embodies a widely held desire in South African foreign policy circles to create alternative structures to those perceived as dominated by Western powers. But the incident was particularly newsworthy because of what it revealed about the gulf between South Africa’s military leadership and the civilians to whom, constitutionally, that leadership should be accountable.

The timing of the exercise, which spanned January 9 to 16, coincided with the violent Iranian crackdown on a mass civilian uprising aimed at fundamentally changing the nature of the Iranian government. Whether the optics of working with Iranian security forces as they massacred their own citizens troubled him or not, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa reportedly was concerned that doing so would worsen the already deeply troubled U.S.-South Africa relationship. Thus, President Ramaphosa expressly directed that the Iranian navy should not participate. And yet, they did.

Predictably, the U.S. Embassy in Pretoria complained about South Africa “cozying up” to the Iranians. But the fallout for the U.S.-South Africa relationship is a secondary issue. Rather, the incident exposed an alarming disconnect between the civilians constitutionally and democratically empowered to set policy, and South African military officials who appear to have simply disregarded lawful instructions.

South Africa’s Defense Minister issued a statement asserting that all parties had been informed of the President’s directive and committing to establish a Board of Inquiry to investigate what happened. But the critically important issue of whether or not the chain of command was simply ignored risks being lost in debates about how South Africa should respond to the United States’ neo-imperialist turn or what the nature of South Africa’s relationship with Iran should be, an issue also amplified by South Africa’s abstention from a resolution at the United Nations Human Rights Council aimed at broadening the UN’s investigation into Iran’s repression. Those are urgent, important topics that need discussion and exploration, but a situation in which South Africa’s armed forces are pursuing their own ideas about geopolitics is a five-alarm fire.

Accountability is often elusive in South African senior circles—in part because the African National Congress, the party Ramaphosa leads, is not just one part of a coalition government, but is also an entity divided against itself. Holding the party together has often come at the expense of imposing any real consequences to those undermining the government’s decisions and directives. This is not the first time South African military leaders appear to have gotten out over their skis when it comes to Tehran. It’s worth watching closely to see whether the issue fades into memory with no actual clarity about just what happened. South Africa prides itself on its hard-won democracy. Whether or not its leaders will acknowledge it, an unaccountable military is a serious threat to that precious asset.