Source: Sahan – Somali Wire – Issue 921 | February 4, 2026

Yesterday morning, Mogadishu residents were woken by a noise unlike the usual dawn bustle of bajaj taxis — F-16 Viper fighter jets sweeping over the city. Beyond the shock and awe of the newest batch of Turkish military hardware in the Somali capital, it was the latest potent symbol of the centre stage Somalia has taken within Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s grand neo-Ottoman vision. As if in a military parade, Turkish drones, jets, helicopters, and warships have all made appearances in Somalia in recent weeks, displaying some of Türkiye’s latest homegrown tech —as well as the F-16s licensed from Lockheed Martin. And so, the steady militarisation of bilateral relations—and Ankara’s penetration of Somalia’s security sector—continues apace.

For some time, Ankara has sought to restructure the Somali National Army (SNA) and impose its own model on the Somali military—just as the Somali president’s own Justice and Solidarity Party (JSP) has been modelled on the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated AKP Party in Türkiye. The current structure of the hapless Ministry of Defence, led by the hawkish Ahmed Fiqi, is believed to be destined for the Turkish chopping block as well, with Ankara similarly seeking to reconstitute the department in its own image. But with the agreed-upon federalised National Security Architecture from 2017 long abandoned, one can expect a far more centralised security model in its place– epitomised by the launch of the new Defence Board this week, nominally intended to “align operational objectives, institutional reforms and national leadership decisions.”

Today, too, a new Chief of Defence Forces (CDF) will be inaugurated at the purported request of the Turkish government, with Brigadier General Ibrahim Mohamed Mohamud formally assuming his new post. Few will mourn the unceremonious exodus of Odowaa Yusuf Rageh as CDF; his premiership will mostly be remembered for acquiescing to Villa Somalia’s continued politicisation of the SNA and his own flight from Adan Yabaal last April when Al-Shabaab overran the town in Middle Shabelle. But his replacement appears, on first glance, potentially even more inept, with Mohamud having no combat experience and having been rapidly promoted through the ranks via his affiliation with Ankara. Rather than bringing aspirations to reconstitute an alliance against an ascendant Al-Shabaab, the concern is that the new CDF will serve as a conduit for Turkish interests —and those opposed to such stakes extend well beyond the confines of Al-Shabaab.

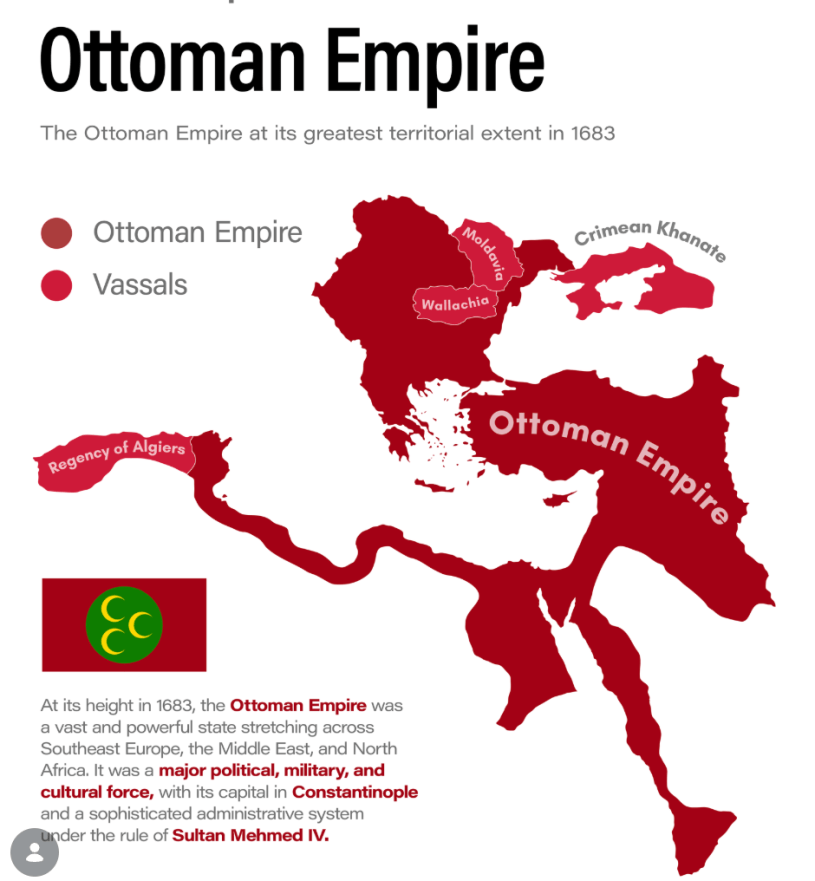

Particularly since the Ethiopia-Somaliland Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in 2024, Villa Somalia has come to count on Ankara as its most dependable foreign ally. Bound by a shared Islamist politics and linkages established during Hassan Sheikh’s first administration, Somalia’s federal government has been eager to hand over the keys to the kingdom to Türkiye, including the prospect of billions of barrels of offshore oil and gas in a wildly unbalanced deal. Injections of military aid have followed, as have proclamations by senior Turkish officials of “protecting” Somalia; routinely harking back to the days when parts of the Somali coast fell under Ottoman rule.

Onshore, meanwhile, Turkish military stakes have particularly settled on the airstrip around Warsheekh in Middle Shabelle, the site of Ankara’s proposed ‘space’ launch site. Nominally intended to launch satellites from, Somalia’s equatorial position and long coastline also make it an ideal launching pad for ballistic missiles. Following Al-Shabaab’s raid on several nearby villages in January, the deployment of these F-16 jets to Mogadishu appears intended to help shore up Türkiye’s considerable military stakes and hardware. Despite yearnings from some ardent nationalists that these jets might even be deployed to shoot down Somaliland President Abdirahman Irro, their mandate is understood to be–thankfully– more confined.

It was little coincidence either that the first port of call for Somali President Hassan Sheukh Mohamud following Israel’s unilateral recognition of Somaliland on 26 December was Ankara. There, further military cooperation pledges were ostensibly thrashed out away from the prying eyes of the Somali parliament, most prominently agreeing upon a Turkish military base in Laas Qoray in the contested Sanaag region on the Gulf of Aden. A riposte to Israeli and Emirati interests along the waterway, Turkish warships were deployed offshore soon after. Site surveys and initial reconnaissance have already been carried out, and the prospects of rivalrous Middle Eastern military installations along the Gulf of Aden– Israeli in Berbera and Turkish in Laas Qoray– may now be a matter of time. Many of these defence and resource agreements have bypassed meaningful parliamentary scrutiny, sitting in a legal grey zone that stretches — if not outright violates — Somalia’s provisional constitutional limits on foreign basing and federal resource authority.

Beyond the bristling geopolitical rivalries along the Gulf of Aden, any development of a Turkish base is certain draw the ire of Puntland as well as Somaliland. Already, Operation Onkod (Thunder)—the planned Puntland offensive against Al-Shabaab in the Cal-Madow Mountains—has seemingly been paused, not because of the necessary rest and rotation of its security forces, but because of the belligerent tactics pursued by Mogadishu in Sool and Sanaag backed by its foreign partners. Further, the TURKSOM military base, Ankara’s largest overseas facility, continues to train thousands of Gorgor recruits; a shining beacon of Turkish charity and anti-jihadist credentials. But concerns about an extension of Gorgor training to Laas Aanood are also abounding following the TURKSOM commander’s attendance at the inauguration of Abdikhadir Aw-Ali Firdhiye as North-Eastern State president last month. Construction of a new military base, underwritten by China, has been slated to begin near the Dhulbahante-majority town, possibly at Gooja’ade.

So, on the surface, Turkish military support can appear a stabilising presence, with persistent drone strikes inflicting pain on Al-Shabaab, even if the jihadists have considerable reserves to call upon. And if deployed to the battlefield, F-16 fighter jets could prove another significant asset —if wielded within a broader, cohesive military strategy that takes the fight to Al-Shabaab– and not against Somalia’s subnational administrations. But there are two broader issues here; the first is political, with Turkish influence in Somali politics undoubtedly accentuating the federal government’s centrifugal inclinations. An emboldened President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has shown little regard for the fracturing political settlement, with Turkish money and arms helping to project a strongman image domestically, akin to Erdogan. Yet this is a misnomer: a security sector framed by a foreign power and loyal to a Hawiye cabal cannot unify the country. Rather, it instead risks further fracturing Somalia’s settlement into a handful of externally backed, heavily armed polities. Although the ruling JSP may model itself on its dominant Turkish counterpart, it is highly doubtful that, without foreign assistance, Villa Somalia could maintain its fragile hold over Mogadishu.

The second dimension remains more of an unknown. Impressive Turkish military materiel is useful for keeping Al-Shabaab at bay, though the jihadists are still ensconced on the peripheries of Mogadishu. But F-16s and Akinci drones will not win the war against the insurgents; the answer there is– as ever– political. And perhaps a more concerning conjecture would be that further Turkish military interventions against Al-Shabaab could, at some point, feasibly push the jihadists to move more aggressively into Mogadishu and urban centres to limit their losses.

Viper F-16s are no doubt fearsome weaponry; a staple fighter jet long sought after by American allies and enemies alike. But the Somali political elite in Mogadishu would do well to understand that Turkish self-interest remains at the forefront of all their dealings, not some venerable do-good instinct. And while the sound of jets ripping through the morning air is a potent symbol, they cannot obscure the noise of the Somali state coming apart at its seams.

The Somali Wire Team

Somaila was in turnmoil for years, and it was abandoned to its own by west. In fact, most of Africa had abusive relationships with west. Russia, China and Turks offered better solutions, and it paid off quite fast. Would you prefer Russia or China to step up for this one too?

Of course they dont do it for free either. But being replaced this fast, should tell you something important.