By Girma Berhanu Eurasia review

Introduction

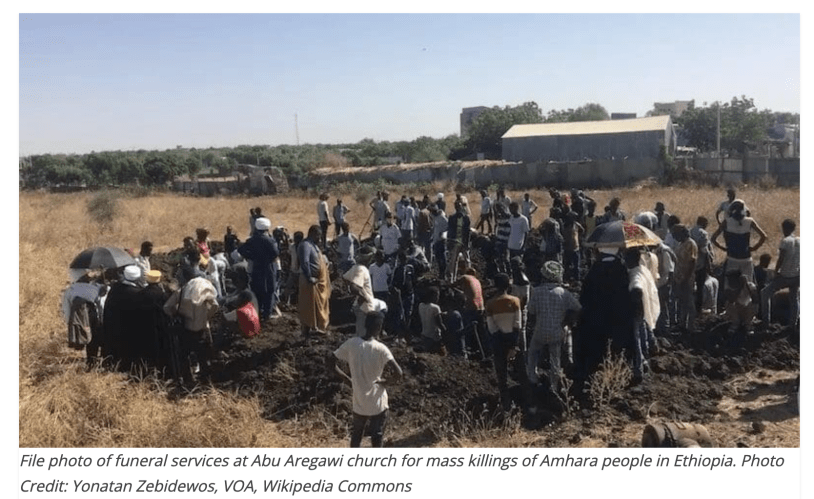

Reports of targeted violence against Amhara academics and professionals have raised growing concern about the safety of intellectual communities in Ethiopia. Some scholars trace these patterns to longstanding political tensions following the 1991 transition of power, arguing that ethnicized political structures have contributed to recurring cycles of conflict and insecurity. Although numerous atrocities have been reported over the past decades, many incidents remain insufficiently documented, and international responses have often been cautious, emphasizing allegations rather than legal determinations.

Notably, the past seven years have seen escalating reports of severe violence affecting Amhara civilians, including members of the educated elite. These developments prompt urgent scholarly inquiry into whether such acts reflect broader patterns of persecution and how they should be understood within the framework of international law — particularly in relation to debates surrounding genocide and the potential dismantling of a community’s intelligentsia.

I considered writing about this phenomenon years ago but waited until discernible patterns began to emerge. Today, the puzzle appears more complete, and the pattern more visible — though it remains in need of rigorous documentation and analysis.

My concern is not purely academic. Two years ago, I lost my cousin. He was jogging early one morning near his residence in the Bole area when he was brutally murdered. He was an accomplished surgeon who had practiced medicine internationally, including in Greece and Bulgaria. To the best of my knowledge, he was not politically active and had no known personal enemies. His killers were never identified, and the limited public information surrounding the investigation has deepened the family’s sense of unresolved grief.

Since then, additional cases have been reported involving the deaths of highly educated individuals of Amhara origin. For example, journalist Martin Plaut, a specialist on the Horn of Africa and Southern Africa, described the killing of Dr. Tsegahun Sime in an article titled “An Amhara doctor killed by the Ethiopian military” (4 February 2026). According to the report, Dr. Tsegahun — a medical professional working at the Amhara Regional Health Bureau — was allegedly detained by security personnel in Bahir Dar and killed several hours later. Colleagues stated that they were unaware of any reason he might have been targeted. Accounts cited in the article describe security forces arriving in a coordinated manner, reportedly under the pretext of receiving guests from the Federal Health Bureau. Dr. Tsegahun was detained around 9:00 a.m., taken for interrogation, and later reported dead after approximately four hours in custody. Witnesses familiar with the events stated that authorities searched his residence, confiscated electronic devices, and subsequently returned his body to the family. The motive for these actions remains unclear based on publicly available information. Commentators have further suggested that, over the past two years, several young Amhara health professionals have been killed under suspicious circumstances. Some reports allege that detainees have later been found deceased, sometimes with their hands bound, in different parts of urban areas. These claims underscore the urgent need for independent investigation and systematic documentation.

Taken together, such cases raise difficult but necessary questions: Are these incidents isolated manifestations of insecurity, or do they indicate a more deliberate pattern of violence against a particular social group? Addressing this question requires careful empirical research, methodological rigor, and restraint from premature conclusions. Only through sustained scholarly and legal scrutiny can the nature and scope of these acts be properly understood.

Targeting of Amhara Intellectuals, Doctors, and Scholars in Ethiopia

The reported targeting of Amhara intellectuals, doctors, and scholars must be examined within the broader context of Ethiopia’s protracted political instability, ethnic polarization, and armed conflict. Multiple human rights reports, media accounts, and survivor testimonies document killings, arbitrary detention, intimidation, and professional marginalization affecting Amhara professionals. While patterns of violence are evident, analysts caution that individual incidents vary in motive, perpetrator, and context, underscoring the need for rigorous, case-specific investigation rather than generalized attribution.

This analysis is informed by long-term observation, original documentation, and sustained engagement with associates of victims. It seeks to differentiate between empirically documented incidents, evolving conflict dynamics, and interpretive or advocacy-based claims. Nonetheless, the cumulative evidence suggests that violence against Amhara civilians—particularly members of the intelligentsia—constitutes a distinct and troubling dimension of Ethiopia’s wider ethnic and political violence.

The targeting of intellectuals warrants particular analytical attention. Comparative genocide and mass-atrocity scholarship demonstrates that systematic attacks on educated elites often function to erode a group’s social cohesion, institutional memory, and capacity for political organization. In this regard, reported killings and intimidation of Amhara professionals raise serious concerns regarding intent and pattern, even as questions of coordination and central direction remain contested and require independent verification.

This study proceeds from the hypothesis that violence against Amhara intellectuals forms part of a broader campaign of persecution against the Amhara population. While definitive conclusions regarding genocidal intent demand careful legal and empirical scrutiny, the repeated nature of the attacks, their concentration in specific regions, and their apparent focus on professional and community leaders warrant further investigation under international human rights and atrocity-crime frameworks.

As Peebles (2023) argues in Ethiopia: Amhara People, Betrayed, Persecuted and Ignored, Ethiopia’s political landscape has increasingly been shaped by ethnic nationalism and exclusionary ideologies. According to his analysis, Amhara communities residing in the Oromia region have faced sustained violence attributed to Oromo nationalist actors, including the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), Oromo Special Forces (OSF), and affiliated youth groups. He further contends that these actions have occurred in an environment of state tolerance or acquiescence, though such claims remain subject to debate and require corroboration through independent investigations.

The targeting of Amhara intellectuals has become more visible in recent years, at times occurring through overt executions and, in other cases, through less transparent forms of violence. Historically, however, this phenomenon is not unprecedented. Earlier episodes—including the sudden deaths of prominent Amhara intellectuals and the summary dismissal of forty-two professors from Addis Ababa University in the early 1990s—suggest a longer trajectory of political exclusion and repression affecting Amhara academic and intellectual life.

In conclusion, while existing evidence does not yet allow for definitive attribution of a single, centrally coordinated campaign, the convergence of documented violence, historical precedent, and contemporary political dynamics indicates a systematic pattern that merits sustained scholarly attention. Further research grounded in detailed case studies, forensic documentation, and comparative atrocity analysis is essential to assess the scope, intent, and accountability of violence directed against Amhara intellectuals and professionals.

In his concluding remarks, Graham Peebles emphasizes that while sustained diplomatic and political pressure should be applied to Western governments—and particularly to the United States administration—the primary source of hope does not reside in Washington or Brussels. Rather, it lies with the people of Ethiopia themselves. Peebles argues that extremist movements such as the OLF/OLA exploit collective fear; indeed, they are sustained by environments characterized by insecurity, distrust, and social fragmentation. Such groups flourish where intercommunal suspicion and political polarization prevail.

Accordingly, Peebles contends that the most viable path toward peace and social cohesion lies in grassroots solidarity: the coming together of Ethiopia’s diverse ethnic and social groups to collectively reject division, manipulation, and hate. It is this internal process of civic unity and mutual recognition—rather than external intervention—that offers the most credible foundation for long-term stability, reconciliation, and social harmony.

Why the Atrocities Against the Amhara Have Not Been Legally Designated as Genocide

The absence of a formal legal designation of genocide in relation to the violence against the Amhara people is, in several respects, puzzling and deeply troubling. At present, major international institutions—including United Nations bodies, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and U.S. government reports—generally characterize the abuses in the Amhara region using terms such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, unlawful killings, and arbitrary detention, rather than genocide. This reluctance persists despite the scale and severity of the violations.

The distinction matters because, under international law, genocide carries a specific and exceptionally high evidentiary threshold. To establish genocide under the 1948 Genocide Convention, investigators must demonstrate specific intent (dolus specialis) to destroy, in whole or in part, a protected group defined by ethnicity, nationality, race, or religion. In practice, this requires proof not only of widespread or systematic violence, but also of intent manifested through official policies, explicit orders, coordinated actions, or consistent patterns that can reasonably be inferred as aiming at group destruction.

In many conflicts, even extreme and sustained atrocities are not legally classified as genocide unless this intent can be conclusively demonstrated. Importantly, the absence of a genocide designation does not imply that the crimes committed are minor. War crimes and crimes against humanity represent some of the gravest violations of international law. Moreover, legal classification often lags behind events on the ground, sometimes taking years and depending on the outcomes of international investigations, commissions of inquiry, or judicial proceedings.

International reporting has documented unlawful killings, drone strikes, mass arbitrary detentions, and widespread repression affecting civilians in Ethiopia’s Amhara region. While these acts unquestionably constitute serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law, whether they meet the legal threshold for genocide remains contested within international legal discourse. This discursive hesitation has had tangible consequences: the scale of Amhara suffering has been muted in global forums, and the deaths of Amhara civilians have failed to receive the sustained international attention they warrant.

Some analysts argue that, in active conflict zones, professionals such as doctors, academics, and judges may become targets because state authorities suspect them of aiding opposing forces, even when they are providing neutral or humanitarian services. Since 2023, armed confrontations between Ethiopian federal forces and the Fano militia in the Amhara region have created an environment in which professionals are frequently accused of supporting one side or the other. There are credible reports of medical professionals being beaten, arrested, intimidated, or killed after being accused of treating wounded fighters. Hospitals have reportedly been raided, and patients detained on the basis of mere suspicion.

Human rights organizations further report that the conflict has been accompanied by an extensive crackdown on dissent. Amnesty International has documented mass arbitrary arrests targeting academics, judges, civil servants, and other influential figures, warning that such practices severely undermine freedom of expression and the rule of law. Authorities have justified these actions as necessary to “stabilize the Amhara region,” yet the selective targeting of educated and professional classes raises serious concerns about political repression and collective punishment.

Others interpret these abuses as part of a broader pattern of communal and political violence affecting multiple ethnic groups across Ethiopia. Widespread harassment and detention of journalists and human rights defenders have driven many into exile, significantly limiting independent documentation of abuses in conflict-affected areas. These conditions further complicate efforts to establish legal accountability at the international level.

Regardless of the explanatory framework adopted, there is substantial evidence of killings, attacks, arbitrary arrests, and intimidation disproportionately affecting Amhara professionals, scholars, and community leaders—often described as the “intelligentsia” or social backbone of the Amhara community. Collectively, these practices have created an exceptionally high-risk environment for educated Amhara individuals. Whether or not these acts are ultimately adjudicated as genocide, their cumulative impact is the systematic dismantling of the community’s intellectual, moral, and organizational leadership.

To date, no international court or UN body has formally declared that a genocide is occurring against the Amhara people. However, the United Nations has repeatedly warned of the presence of risk factors for genocide in Ethiopia. The UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide has highlighted continued ethnic targeting, credible reports of serious violations against civilians—including Amhara populations—and patterns of violence that warrant urgent preventive action. Some scholars and advocacy groups argue that the threshold for genocide may already have been met, although this remains legally unproven.

Under the Genocide Convention, genocide requires demonstrable intent to destroy a protected group, not merely large-scale or indiscriminate violence. Courts typically require compelling evidence of: (1) intent to eliminate the group, in whole or in part; (2) systematic actions directed toward that objective; and (3) a degree of coordination suggestive of policy or organized practice. Based on several years of research, documentation, and analysis, I contend that these criteria are present in the case of the Amhara. In particular, the targeting of the Amhara intelligentsia appears aimed at uprooting the educated class that serves as the voice, memory, and organizational foundation of a historically marginalized population.

The Ethno-Political Crisis in Ethiopia: Targeting Intellectuals, Cultural Erasure, Historical Revisionism, and the Psychology of Power

One explanation advanced for the targeting of Amhara professionals concerns the role of malicious envy, rooted in a widespread perception that Amhara intellectuals have historically demonstrated high levels of professional competence, ethical conduct, and moral authority within Ethiopian society. This perception, whether accurate or constructed, has rendered Amhara professionals symbolically threatening in periods of intense ethno-political competition.

As argued in my previous report, Ethiopia is currently experiencing one of the most profound socio-political and cultural crises in its modern history. The country is witnessing what may be characterized as a form of ethnic apartheid, manifested through atrocity crimes, the systematic targeting of the intelligentsia, state-led cultural destruction, and the fragmentation of Ethiopian national identity. Central to this crisis is a political order dominated by actors aligned with Oromo ethno-nationalist ideology, who exert disproportionate influence over key state institutions, including the military, political apparatus, economy, and social infrastructure.

Under the rubric of ethnic federalism and political empowerment, there has been a sustained effort to dismantle the symbolic and institutional foundations of Ethiopian statehood—particularly those associated with Amhara heritage and the broader Ethiopian national project. Historic sites have been deliberately destroyed, urban neighborhoods razed, and long-established communities forcibly displaced to the margins of major cities, including Addis Ababa. These acts constitute not only material destruction but also symbolic violence directed against collective memory, belonging, and historical continuity.

Concurrently, the Amharic language—long the lingua franca of the Ethiopian state—has undergone systematic marginalization. Cultural traditions associated with Ethiopian identity, many of which are closely linked to Orthodox Christianity and Amhara historical experience, have been either sidelined or actively suppressed. This multifaceted assault may be conceptualized as culturicide (the destruction of cultural identity), linguicide (the erosion or elimination of language), and historicide (the erasure or revision of historical narratives). These processes build upon a longer trajectory of ethnocide and have recently been accompanied by the targeted killing of Amhara intellectuals.

A particularly troubling dimension of this transformation is the appropriation and rebranding of national symbols, histories, and cultural heritage as exclusively Oromo or as belonging solely to the Oromia region—often articulated through ideological frameworks such as Kegna. This dual process of cultural dispossession on the one hand, and cultural monopolization on the other, raises important political and psychological questions regarding power, identity, and legitimacy.

One explanatory framework lies in the psychosocial dynamics of identity politics, particularly the interaction between malicious envy and collective inferiority complexes in the formation of ethno-political ideologies. Malicious envy denotes a destructive orientation in which the objective is not merely to attain parity with another group, but to strip that group of its status, achievements, and symbolic capital. An inferiority complex, by contrast, reflects deeply internalized feelings of inadequacy, often arising from perceived historical marginalization, exclusion, or unfavorable social comparison.

Both dynamics are associated with low collective self-esteem and tend to produce compensatory political behavior—such as exaggerated identity claims—or aggressive strategies aimed at displacing or delegitimizing the “other.” In the Ethiopian context, these psychological dispositions appear to inform the rhetoric and policy choices of certain segments of the Oromo nationalist elite, whose discourse reveals both resentment toward Ethiopia’s historical national identity and a determination to reconstruct the nation’s narrative through a narrowly defined ethno-nationalist lens.

The outcome of this process is not an inclusive or pluralistic federation, but rather an emerging project of ethno-hegemony that fundamentally undermines national cohesion. Its consequences are far-reaching: the erosion of shared civic identity, intensified ethnic polarization, and the gradual dismantling of a historically multi-ethnic and culturally rich civilization.

If left unchallenged, this trajectory poses a serious threat to the long-term viability of Ethiopia as a unified political entity. It demands urgent scholarly, political, and civil society engagement—not only to address the immediate manifestations of violence, displacement, and repression, but also to confront the deeper ideological and psychological forces driving this destructive transformation.

Politics, in this sense, functions as a particularly fertile arena for the expression of malicious envy at the collective level. As power, resources, and symbolic authority are contested, ethnic identities become increasingly politicized, intensifying intergroup rivalry. In Ethiopia, political parties, ideological factions, and regional administrations are often inseparable from ethnic identity. When one group consolidates political dominance, rival groups may experience not only a desire for comparable influence, but also a destructive impulse to discredit, weaken, or erase the status of their perceived adversaries. These dynamics fuel polarization, obstruct compromise, and foreclose meaningful dialogue.

Recognizing the role of malicious envy at the group level offers valuable insights into intergroup conflict beyond conventional material or institutional explanations. It highlights the emotional, symbolic, and identity-based dimensions of rivalry, underscoring that such conflicts are driven not only by competition over resources, but also by struggles for recognition, dignity, and historical legitimacy. Acknowledging these dynamics is essential for developing conflict resolution strategies grounded in shared identity, equity, and cooperation rather than zero-sum ethno-political competition.

Like what your read?

Please consider supporting Eurasia Review, and thanks for you consideration!

Girma Berhanu

Girma Berhanu, Department of Education and Special Education (Professor), University of Gothenburg