Source: The Ethiopian Cable

Note: This is an excellent summary. However, I disagree with this assessment: “The Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission, tasked with issuing a “final and binding” ruling, floundered after issuing a 2002 ruling that Badme belonged to Asmara.”

The Boundary Commission was required under the Algiers Agreement to rule on where the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia lay, based exclusively on custom and colonial maps. This they did. Badme was awarded to Eritrea and that – legally – was the end of the matter. Despite Ethiopia having sworn to abide by its ruling, the Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi then attempted to wriggle out of it, and was reprimanded by the UN Secretary General for doing so. Despite Ethiopia’s claims, the border remains legal under international law. It can only be altered by mutual agreement of both nations.

Martin

| Issue 318 | 10 February, 2026 |

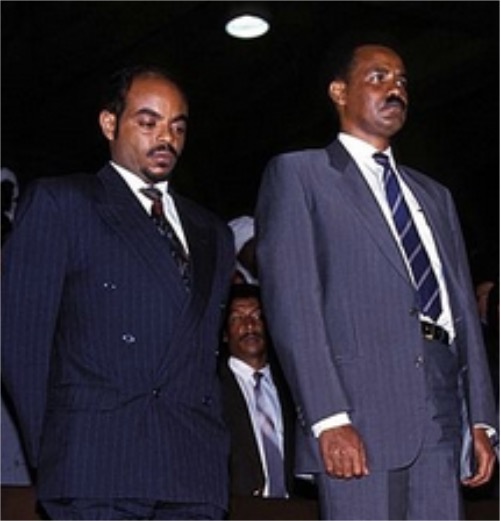

| There are rivalries born from distance, and rivalries born from closeness. Nearly three decades of Ethiopia-Eritrea feuding —barring the brief, destructive interregnum in Tigray —is borne of the latter. The depth of the socio-cultural linkages between modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea dates back centuries, with the shared highlands part of the sophisticated Axumite kingdom that stretched into the Arabian Peninsula. But as ever, the tyranny of geography is a blessing and a curse, and the friction between Ethiopia and Eritrea has long been underpinned by a persistent failure to define their relationship at four key junctures; post-independence, post-2000 war, post-reconciliation in 2018, and post-Pretoria. First, it is worth addressing the latest reworking of their corroded ties by Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed in parliament, who wrongly attributed the relationship breakdown to the atrocities committed by Eritrea during the Tigray war, citing massacres in Shire, Axum, and Adigrat. Whitewashing the crimes of the Ethiopian military, Abiy even asserted that his officials had been dispatched to plead with Asmara over their conduct. Few are buying such blatant revisionist histories; the Eritreans worked hand in glove with the Ethiopians, including in Axum, where Addis’s forces failed to intervene as the Eritrean military went house by house, killing indiscriminately. Not only that, but Abiy’s latest claim drew an immediate rebuttal from former Foreign Minister Gedo Andargachew, whom the PM claimed had been repeatedly dispatched to Asmara to protest Eritrean military conduct. Andargachew, however, contended that his mission to Eritrea in January 2021 was to congratulate—not object to– Asmara’s behaviour. Eritrean Information Minister Yemane Gebremeskel further dismissed Abiy’s claims as deliberate falsehoods intended to rationalise future war. But taking the longer view of Eritrean-Ethiopian relations, today’s mutual discord has broadly defined relations since Eritrea’s independence in 1993. During the long attritional war with the Derg regime, though the twin Eritrean and Tigrayan resistances to the Addis regime shared a Marxist ideology, as well as strategic operations, there were points of contention. Most famously in 1985, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) severed the supply lines of their Tigrayan partners to Sudan at the height of a raging famine. Still, when the Derg collapsed in 1991, both fronts took power, and for a brief moment, it appeared that two ideologically aligned governments might inaugurate a new regional order. But it was not to be. The subsequent 1993 independence referendum, which overwhelmingly affirmed the Eritrean people’s wish for freedom, marked the pinnacle of their bilateral relations, even if Abiy and others seek to deny its legality today. The new border was flung open, with Asmara still using the Ethiopian birr as its currency, as the Eritrean port of Assab hummed with imports for its southern neighbour. But a failure to capitalise on the bonhomie would prove its undoing, as well as the autocratic turn of the Eritrean regime. Indeed, both regimes emerged from tightly controlled liberation movements, not pluralistic civic orders, with decision-making highly centralised and personalised, and institutions weak or deliberately sidelined. At every moment when technical, rules-based, bureaucratic cooperation was required, both sides defaulted instead to leader-driven politics; a style ill-suited to managing sovereignty between former comrades. In particular, no formal demarcation of the border took place, even though colonial maps were inconsistent and villages– such as famously Badme– existed in a liminal space of administration. And as the 1990s drew to a close, relations soured further, including over Eritrea’s introduction of the Nakfa in 1997 and port fees. And the subsequent year, a clash over Badme spilt over into a vast, futile war that lasted two years, leading to tens of thousands killed. Though the Algiers Agreement, signed in December 2000, may have ended active hostilities, it did little to resolve the root causes of the conflict and lacked crucial political buy-in. Persistent calls for clarification on the amendment to the vague and fraught Pretoria agreement from 2022 have distinct echoes of the 2000s as well. The Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission, tasked with issuing a “final and binding” ruling, floundered after issuing a 2002 ruling that Badme belonged to Asmara. And though Ethiopia nominally accepted the ruling, it continued to call for dialogue on several issues to stall implementation, while both parties sought to undermine the agreement’s limited provisions. Post-war, Meles Zenawi’s government subsequently sought to systematically —and effectively —constrain Eritrean influence in the region in the 2000s, leveraging its status as the regional hegemon. An embittered Asmara, on the other hand, was no doubt the ‘spoiler’ of the Horn, warring with Djibouti, with Sudan, instigating instability in Ethiopia, and even supporting Al-Shabaab in Somalia. Indefinite national service and a siege mentality reigned, with Asmara brutally repressing any glimmer of opposition or freedoms at home. The third ‘failure’ of bilateral clarification came in 2018, with the sudden rise of Abiy to the tiller in Addis and the subsequent Gulf-brokered ‘peace’ bringing the young leader hand in hand with the despot in Asmara. Early signs of trust-building, including the resumption of flights and a brief reopening of the border, sparked a flurry of unearned optimism, earning Abiy a Nobel Peace Prize– and notably not his Eritrean counterpart. But the performative politics soon run aground, with any attempts to institutionalise these apparent linkages failing. And yet the rapprochement was never truly about normalising Eritrean-Ethiopian relations, but rather about reorganising regional power. The wily Isaias, in particular, wielded the agreement to escape isolation and neutralise his friends-turned-foes in Mekelle, while Abiy sought to reshape Ethiopia’s internal balance of power. The cost of the normalisation was steep– hundreds of thousands of Tigrayan lives in the 2020-2022 war, with a litany of atrocities carried out by Eritrean and Ethiopian forces. Despite the revisionist histories being propagated by apologists for either regime, the Ethiopian and Eritrean armies are both culpable for the host of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Tigray. The fourth is the Pretoria agreement. Eritrea was not a signatory to the rushed, patchy accord signed in November 2022 that ended the hostilities of the Tigray war, but it has been Addis that has systematically sought to undermine the fragile cessation of hostilities agreement. The failure of the accord to bring in all parties, and to begin working towards a shared political understanding of the war itself, is now unravelling across multiple theatres. It has accentuated the conflict in Amhara, where the Eritrean-backed Fano insurgency continues to rage, while the situation in Tigray– as well as between Addis and Asmara– teeters back on the edge of full-blown conflict. Another diplomatic tit-for-tat concerns Addis accusing Eritrea of maintaining forces in Ethiopia, a claim categorically denied by Asmara in recent days. The nature of the politics of Asmara and Addis today hardly lends itself to a structural, formalised relationship. The first remains dominated by a cabal of ageing People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) members, with the militarised shell-state itself wholly under their control. Ethiopia, on the other hand, has degenerated into a vying court for Abiy’s attention, with the corruption of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front-era giving way to cannibalistic proportions. Neither leader appears much inclined towards a bureaucratic form of governance, nor durable foreign relations– an issue further accentuated by the particularly accentuated rivalrous politics of the Gulf at this moment. This might allow another sudden coming-together over Red Sea access, perhaps brokered by one of their Gulf patrons again, but it is highly doubtful that it can be stable. And so each moment of peace has carried within it the seeds of the next rupture — a rivalry born of closeness unmanaged. The Ethiopian Cable Team |