‘Unbroken Chains: A 5,000-Year History of African Enslavement’ by Martin Plaut (2025); C. Hurst and Co. Publishers Ltd; London; 307 pages (Book review by Graeme Kemp)

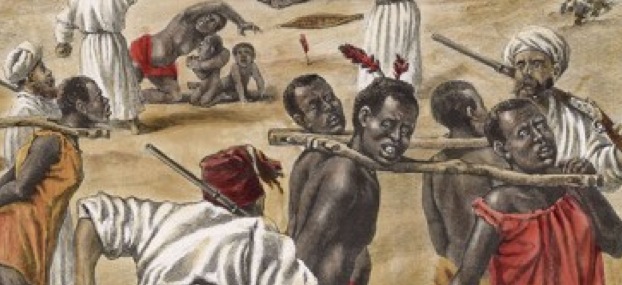

Source: The Equiano Project

Feb 20, 2026

By Graeme Kemp

In August 1625, sixty adults and children were seized from Mount’s Bay in Cornwall in the west of England. Fishing boats from coastal towns such as Penzance and Looe were boarded, their crews taken and their vessels left to drift. The captives were transported across the Mediterranean and sold into slavery.

Remarkably, this enslavement came not from Europe but from North Africa. The Barbary corsairs sailed from ports in what are now Tunisia and Algeria, raiding European coastlines for captives. Other expeditions were launched from Tripoli. As Martin Plaut explains in Unbroken Chains, Thomas Ceely, the mayor of Plymouth, complained to the authorities about the scale of the threat. In a single year, a thousand sailors were taken from the region. In one ten-day period alone, twenty-seven ships and 200 people were seized.

Incredibly, the island of Lundy in the Bristol Channel was used intermittently as a corsair base between 1625 and 1636 to conduct raids on the English coast. The danger was so severe that shipowners in ports such as Southampton, Barnstaple and Plymouth were reluctant to put to sea. The Barbary pirates operated under the protection of the Ottoman Empire, giving their activities geopolitical backing.

Transported to North Africa, European captives were treated brutally and humiliated in slave markets. Female virgins were particularly prized as sex slaves. Mortality rates were high; Plaut notes evidence suggesting that up to 20 per cent of such slaves died annually in the seventeenth-century Maghrib. The probable mortality rates among these European slaves may even have exceeded those among enslaved Africans working on sugar plantations in the Americas.

This history of European enslavement by North African states is shocking. Yet Unbroken Chains is not written as a provocation but as a serious, nuanced history of Africa and slavery. Plaut notes that between 1580 and 1680 roughly half of all Barbary captains were themselves of European origin. Unemployment among sailors appears to have fuelled this phenomenon, with Dutch and English mariners among those who joined corsair fleets.

The book challenges many popular assumptions, including the idea that slavery in Africa was always imposed from outside the continent and that the Trans-Atlantic slave trade was the only significant form of African enslavement. Plaut also disputes the claim that Britain was the dominant Trans-Atlantic slave-trading power, arguing instead that Portugal began earlier and finished later than any other European state.

A sobering table in the book sets out the scale of multiple slave systems: the Indian Ocean trade (800–1900), the Trans-Atlantic trade (1501–1867), the Trans-Saharan trade (650–1800), the Barbary corsair trade (1530–1869), Ottoman slavery (1800–1900), slavery under the Sokoto Caliphate, Iran (1800–1900) and Ethiopia (1935). Plaut estimates that more than 41 million people were enslaved across these systems. The book concludes with a discussion of contemporary slavery in Africa and how it might be ended.

Plaut stresses the importance of historical honesty and complexity. Quoting the Ethiopian scholar Mekuria Bulcha, he writes that the notion that slavery was simply imposed on Africa by “white Christians from Europe and Muslim Arabs from the Middle East and Asia” has no basis in history. Africans themselves engaged in slave trading for centuries before external intervention and, in some regions, enslavement persists to this day.

He explains, for instance, how the Sokoto Caliphate, which spanned northern Nigeria and Niger and extended into parts of modern Cameroon and Burkina Faso in the nineteenth century, was a state fundamentally structured around slavery. Plantation labour formed the backbone of its economy. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Asante in present-day Ghana also used slaves to strengthen their armed forces, enhancing the power of African elites.

European culpability is not minimised. The Portuguese enslavement of people in Angola was catastrophic. Exploiting divisions within the Kingdom of the Kongo caused by civil war, Portugal extracted an estimated 1.3 million people between 1500 and 1700. The Kingdom of the Kongo itself relied on slave soldiers. The book also features illustrations, including a photograph of the influential Zanzibar slave trader Hamad bin Muhammad al-Murjabi, who controlled large parts of central Africa.

The final chapters turn to slavery in Africa today. Plaut describes what he calls “racial slavery” in Mauritania, where ‘white’ Moors or Beydane dominate ‘black’ Moors or Haratine. He also examines contemporary slavery in Mali, Niger, Sudan and Libya. Organisations such as the African Union, the Arab League and the United Nations, he argues, have been slow or ineffective in confronting chattel slavery and related abuses in recent decades. Slavery remains a grim reality in parts of the continent.

On the question of reparations, Plaut highlights the immense complexity involved. If multiple societies were both perpetrators and victims across different systems, who compensates whom? Why is compensation most often discussed solely in the context of the Trans-Atlantic trade? Should Europeans seek redress for the Barbary slave trade? The historical record does not lend itself to simple moral accounting.

The book contains one minor geographical error, describing Lundy as being in the English Channel rather than the Bristol Channel. Aside from this, Unbroken Chains is an engrossing and thoughtful historical study. It resists simplistic narratives and instead presents slavery as a global, multi-directional and deeply entangled institution. It deserves wide attention and serious discussion.

Buy Unbroken Chains: A 5,000-Year History of African Enslavement (2025) on Amazon here.