In this important intervention Johathan Jansen, Vice Chancellor of the University of the Free State, argues that: “many of the disruptions at the former white English universities is a kind of gangsterism masquerading as progressive politics.”

Martin

The Inaugural Stephen Ellis Memorial Lecture

The Inaugural Stephen Ellis Memorial Lecture

Netherlands Embassy, Brooklyn, Pretoria, Friday 9th October 2015

A quiet contemplation on the new anger: The state of transformation in South African universities

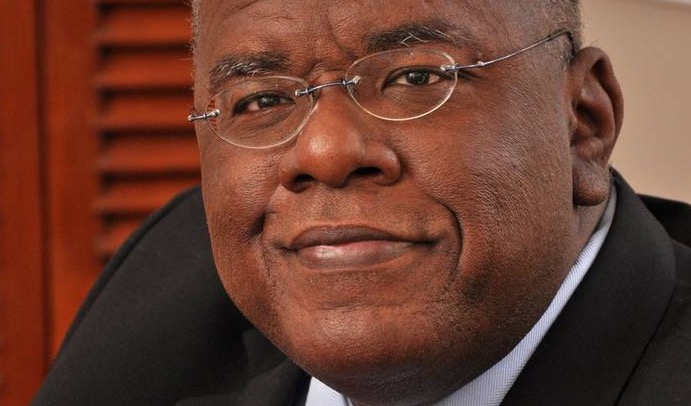

Jonathan D Jansen, University of the Free State

Introduction

From the time of our first meeting Stephen Ellis struck me as a fine English gentleman, a generous human being and a meticulous scholar. I was not surprised that he would be invited to share the honour of Desmond Tutu Professor, an association he always carried with great pride. It was only later, however, that I would come to appreciate the stature of this Oxford-trained historian in the academic world not only as Editor of two prestigious publications, Africa Confidential and African Affairs, but also as author or co-author of a collection of truly outstanding books on the African condition alongside his towering presence in leading world journals concerned with African Studies.

It was however his book External Mission which would behoorlik set the political cat among the self-adulatory pigeons of the ruling party by demonstrating the continuity of behaviours—corruption, racial and ethnic strife, paranoia and excess—before and after 1994. The seamless, unreflective, one-dimensional and heroic accounts of struggle and conquest were shaken by this remarkable work of scholarship which, I am proud to say, had some of its origins in the archives of the University of the Free State. Yet while I do not share Stephen’s preoccupation with the influence of the Communist Party within the ANC—there were hard realities shaping this co-dependency over a century—I know of no other historical work that better explains the state we are in by taking 1994 as a marker of not only change but continuity with the fractured past of the liberation movements, principally the ANC.

I therefore take my courage this evening from the work of Stephen Ellis as I reflect on the present moment, the turmoil on some prominent university campuses, and what it says about our past and future as a young democracy.

In doing so I thank Professor Gerrie te Haar Stephen’s wife and partner, for considering me to do this Lecture, and your unusually charismatic Ambassador, Marisa Gerards, for the invitation and the platform for honouring Stephen in this way.

The new anger

There is a disturbing vignette somewhere in the middle pages of Memoirs of a Born Free, a book by the young black activist Malaika Mahlatsi who renamed herself Malaika wa Azania. As a learner in a middle class white school, she stumbles on the fact that her teacher’s precious dog died. Looking around at the teary group of fellow learners and the heartbroken teacher, Malaika bursts out laughing. “In Soweto, dogs die all the time,” she writes. The school calls the young Malaika on her heartlessness but for the Earth Sciences student at Rhodes University—also a pristine white institution of her choice—the first-time book author would carry that memory of the dismissal of the pain of others as a badge of pride.

I have studied the somewhat unexpected emergence of this new black anger with a mixture of intrigue and concern. Intrigue, because of who the voices are raising this strident critique of post-apartheid society. The critics are mainly middle class black students (or those aspiring to such status) who attended white schools and white universities in South Africa. In other words, they are for the most part children of privilege as far as their educational aspirations are concerned, and unlike the vast majority of young people who enjoyed access to premium institutions and made that experience work for them, their families and communities—this group of disaffected graduates are angry, and appear very angry. The argument of the newly angry is very simple:

Thank you ANC for what you may have done in the struggle, but no thank you. We reject your closed and circular narrative of freedom—that you came, saw, and conquered. That is your narrative, not ours. We are still not free.

Hence Malaika’s sarcastic title, Memoirs of a Born Free. There is an attempt here at a generational break—the old timers with their warm, fuzzy accounts of struggle and victory, and the new generation which does not feel free in the daily grind of forging a living in a white-dominated economy and grasping for learning in untransformed universities. The older generation should stand back and shut up, and allow the next generation to speak unimpeded and express anger unapologetically. In a refrain often heard on the anger platforms: there is an unyielding assault by whiteness on the black body whether in white university classrooms or at white literary festivals or in everyday life.

But I am drawn to the new anger not only by intrigue but also by a deep concern that once again, as Stephen might have put it, the continuity of destructive behaviours from the past show up in the character of student protests now. There was without any doubt a glorious element to student and indeed community protests which helped set us free. But it is time to acknowledge that there was also the dark side which made us like the perpetrators of that crime against humanity. I speak of unbridled anger, intolerance of dissent and violent confrontation which while understandable, to some extent, in the heat of apartheid, cannot possibly define the content and contours of protests after apartheid. That dark side sometimes included complete disregard for the humanity of others such as in the horrific “necklacing” episodes and the torture, even death, of suspects in camps. It included the emphatic dismissal of education—liberation now—and the loss of status for teachers and teaching from which the post-apartheid school system has never recovered. There is that anger and intolerance that still runs in our veins and shows up all too frequently in the way we protest on the streets, on campuses and, dare I say, in Parliament. That behaviour comes from our violent past and continues into the present.

We have not learnt, in other words, how to conduct ourselves in the context of a democratic state. We have lost the dignity of protest exemplified in the behaviours of people like Walter Sisulu and Beyers Naude and Neville Alexander. In other words, there are left unexplored radical forms of protests that are not reducible to violence and insult and the degradation of things we do not like. Too many influential persons who should know better applaud this dehumanising behaviour that comes with the new anger and it is already clear that the long-term costs will be devastating to school and society.

“Fuck-off whites”—the repeated, shocking words of a young man following the presentation of one especially angry black Ruth First Fellow at Wits—might have unsettled the chairman (and the handful of whites and blacks in the audience) but it carried much support among young blacks in the crowded Great Hall of this chronically unsettled campus. The chairman was at pains to condemn this vile behaviour through a conceptual distinction long lost among this class of youth, between anger and hatred. I have sat in enough of these kinds of outbursts to have felt the heat of this native hatred among young people who had not spent a day living under apartheid or a night in the cells of the white regime; but the anti-white sentiment is undisguised.

By the time the Rhodes Must Fall (RFM) moment came along there was at hand a massive, monumental symbol against which this rage could be levelled—the Rhodes statue on the UCT campus. First the image was doused in human excrement and made the subject of daily mockery until finally the statue was pulled down, Saddam Hussein-like, to the cheers of middle class students, some whites in their number, and consigned to a covered destination off the campus. Rhodes just happened to be in the way, a handy target for a collective anger against the institution. A few weeks later, and things had largely died down. The RFM moment was never going to become a movement; anger alone never sustains anything despite sporadic attempts at revival.

But what exactly is the grievance? At first glance, it is hard to tell. As one astute black scholar observes, “there’s a lot of finger pointing in no particular direction.” Looking closer, the institutional critique is much clearer—the anger seems to be levelled against the lack of transformation: too few black professors, a neo-colonial curriculum, an unwelcoming institutional culture, everyday racism on campus. On that score, there can be little disagreement, and most university leaders will show scorecards of progress while acknowledging complexity in overcoming these problems as quickly as we all wish it could be done.

The grievance becomes a little more complex, however, when it moves away from the straightforward target of university transformation (more black professors) to anger in the realm of black/white relationships. This was what the Ruth First lecture promised to bring to light—the complexity of interracial friendships. At this point the anger becomes intense, even threatening for what then happens is a public baring of the soul of something long suppressed—an unrequited love from white friends. We must pause here.

Not all young people struggle with interracial friendships. In fact, it is my observation across schools and universities that most young black and white South Africans eventually “find each other” through the constant negotiation of social and cultural relations that accommodate difference and accentuate sameness. The earlier such friendships start, the better and many such black/white relations blossom into intimate relations and even marriage. How that happens is the subject of my latest book Leading for Change: race, intimacy and leadership on divided university campuses (Routledge 2015) and my forthcoming book Race, Romance and Reprisal (2016). In other words, the angry voices of a minority do not represent the totality of experiences of interracial friendships among youth in post-apartheid society. The volume of angry noise, however, is out of proportion to the breadth of intimate experiences binding black and white youth.

Still, among the disaffected there are nuances in these bouts of anger. Some believe these interracial friendships carry no value and should be stopped. Others castigate whites for entering these friendships on social and cultural terms which favour them, the privileged: to hell with these kinds of friendships. The complaint goes something like this—

“We have to speak their language and suppress our own; they make no effort to learn our languages. We are tired of smiling in friendships which actually demean us, make us feel less. We become like them, except white on the outside even though our essence, the inside, remains black. We are tired of living these two lives, the one representing our poor mothers and families, the other cavorting with whites in the realm of privilege. We are coconuts no more.”

What does this mean? It is important, first of all, to pay attention to this strain of disaffection among black youth. In one sense, it is nothing new. Some time ago Ellis Close made similar points in The Rage of the Privileged Class wherein he described the experiences of African Americans inside the hostile world of corporate America. Notes Close,

“[S]enior corporate executives and senior partners in law firms are … expected to conform to a certain image. And though their positions may not require golden hair and blue eyes, they do require the ability to look like–and be accepted as–the ultimate authority

In other words, even though black students (or executives) more and more enjoy access to white organisations, their presence and progress requires conforming with white standards of achievement. Being physically present, for those who rage, is not enough; being recognised and accepted on their own terms, matters. Close’s problem in capitalist America is much more difficult to resolve than those of the newly angry in South Africa—he lives in a country where black people are a minority and no longer the most important minority in a nation where the growth in the Latino population has recast politics and economics on that side of the Atlantic. And for Close it is about being successful within the capital accumulation model of neoliberal America; for many black South Africans it is about equity, opportunity and recognition.

The problem of social, cultural and intellectual recognition and not only physical access is a common lament expressed very powerfully in segments of student life on the former white campuses in South Africa. Put bluntly, the lament could be described as “we are physically present but in every other way invisible—socially, culturally, intellectually, materially and even symbolically.” In other words, simply adding more black professors to the Senate or broadening the curriculum to include African Studies (or perspectives) or commissioning more studies on institutional culture, will not only do little to pacify this rage; it could make matters worse.

In this respect it is important to distinguish patterns of institutional recalcitrance among different South African universities. Some of the former white Afrikaans universities still have a major problem with the first order of business, and that is physical access. In this respect Stellenbosch University and the Potchefstroom Campus of North West University find themselves in the eye of the transformation storm.

The Open Stellies Movement was long overdue and the Luister video-documentary is merely the start of what will become an extended campaign to open-up undergraduate studies to many more African students. In this respect it is worth noting that OSM is a much better organised and more mature student organisation than RFM at UCT and its spin-off moment at Rhodes University; it is therefore likely to sustain itself through constructive engagements with the university leadership for some time to come.

It is nevertheless sad that the transformation of this otherwise top academic university was held back by decades-old, refractory language crusades to “protect Afrikaans” which, whether intentionally or not, had the happy consequence (for many) of keeping the institution predominantly white and especially non-African in its main protectorate, the undergraduate class.

In the same way the ugly and repeated assaults on the first black Vice-Chancellor of the North West University by the white defenders of the Potchefstroom campus is—once all the flimsy excuses are exhausted—nothing more than protecting white dominance in language, culture and demographics on what used to be called by the explosive code-name of the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education.

The white English universities such as Rhodes, UCT and Wits have a different problem—black student numbers have grown steadily in the past two decades of democracy to a comfortable majority in some instances. The usual complaints apply—more black professors, and so on—but the problem in these institutions is more elusive and complex, as any student of transformation among the English would attest. In fact for many researchers, the difficulty is “putting your finger on the problem.” The Vice-Chancellors boldly speak the language of transformation; they have senior colleagues driving these change programmes; their curricula are in many cases open, progressive and critical of their own foundations; there are any number of funded initiatives to recruit older and promote young black scholars. So what’s the problem?

In the first instance, these institutions still convey an overwhelming sense of whiteness from the complexion of the professoriate to the cultural rituals and symbols of everyday life. But there is more: the places impose an English whiteness on newcomers that is hard to describe. So over the years I have asked my most accomplished black scholars at UCT why they were so angry. The answer was the same time and again, normally conveyed with deep emotion: “It’s the way they make you feel.” Since I have been at the receiving end of a few of those withering white putdowns by prominent UCT academics, I know exactly how that must feel if you lived inside that institutional culture day after day at the mercy of a professor, head of department or dean.

At the Afrikaans universities the racism is often blatant; you see it coming as in the Nazi salute on the Potchefstroom campus or the urinating into food for black workers on the UFS campus or the Blackface episodes on the University of Pretoria and Stellenbosch campuses. At the English universities the racism is much more subtle. It is the snub in the hallway; the put-down remark about your promotion; the sense of cultural superiority; the clipped, foreign-sounding accent; the Oxbridge referencing; the biting criticism of your manuscript; the coldness in relationships; the patronising comment; the talk behind your back; the fear of reprisal if you speak out; the weak-wristed handshake; the inability to hug or deliver an unconditional compliment; and the constant reminder that you are not part of the club, literally.

It is for this reason that black academics at places like UCT quickly found common cause with the RFM students even if they disagreed with their tactics; for many years they too had waited to exhale.

That said, at the core of many of the disruptions at the former white English universities is a kind of gangsterism masquerading as progressive politics. It is a vile, in-your-face hooliganism that conjures up the language of radical politics but is, in fact, nothing less than a tsotsi element that one Vice-Chancellor called this behaviour. By conflating the comtsotsi element with the progressive element in scholarship or journalism or everyday observation, we give recognition to bad behaviour and undermine the seeds of what could become a very powerful movement in student protests. This is a crucial point.

Where does this hooligan behaviour come from—that beats up other students, violently disrupts university meetings, assaults members of staff, spews forth anti-Semitic and anti-white froth, and gratuitously attacks the dignity and integrity of leaders? There is no question that the on-campus behaviour seeks to mimic the off-campus behaviour of political parties, to begin with. The ongoing fracas in Parliament, broadcast for all to see, is the model on which some of these youth base their on-campus tactics. Often the students involved in the more violent confrontations come from political movements and community contexts where intellectual disagreement and tough debates are not enough—it must escalate into physical confrontation and verbal abuse.

Needless to say, this is worrying in terms of our country’s future. If the next generation of leaders resolve their conflicts through hate speech and violence, we sustain the very conditions that apartheid and colonialism embedded in our society. The role of leadership is to change that behaviour and the role of education is to tame those passions. The failure to discipline this particular version of the angry mob is a failure of education and leadership at home, in schools, in community organisations and in our universities.

But to simply dismiss all of this violent rage as irrational is not very helpful either in its resolution. The new anger feeds off unresolved inequalities in school and society. The angry student is hungry on campus, struggling to find finances for tuition, hustles to secure cheap accommodation, and then with a dodgy quality of school education that reflects in his poor academic results, finds himself in a laboratory or lecture hall where whites are in charge and continues therefore to make a direct connection between his miserable state and the race of the lecturer. In former white institutions with their cold, clinical and alienating institutional cultures which fail to recognise this student and his estrangement, fire and oil meet.

In this tight and twisted bundle of raw emotions, what appears as anger is not always clearly articulated and there is no particular enemy, so everyone is—the Vice-Chancellors, the white university, white staff, all whites, unsympathetic blacks etc.

The political philosophy of the critique is similarly dense and confusing, ranging from a broad pan-Africanism to a narrow black ethnic nationalism with more than a hint of a poisonous anti-white racism. And the language of critique is straight out of an introductory social science course, repeatedly referencing harm done to “the black body”—for example, by being a minority in a largely white literary festival—with a fair amount of exaggeration, to put it mildly. Simply to go to classes at Rhodes or UCT is to “subject the black body” to an unrelenting oppression.

All kinds of figures are therefore invoked in these angry flashes from Biko to Fanon to Cornell West but unsurprisingly not King or Ghandi or Mandela. If Mandela gets any mention at all, it is as a sell-out, the man who led South Africa into a soft transition that left white privilege undisturbed and black poverty undiminished. It is this instant re-interpretation, and dismissal, of Nelson Mandela that is the most marked feature of the new anger.

There is no ideology or memory or history here, only a hodge podge of pro-black/anti-white sentiment on the tip of an angry tongue that finds expression in the lashing out at public gatherings and memorial lectures, in newspaper columns of especially the Sunday Independent though with more balance in City Press, and in the occasional book production.

It is an anger that is particularly vicious of its critics. In its milder forms of dismissal the critics are old, representing a bygone generation that simply by virtue of age is out of touch and irrelevant to the struggles of youth. They should allow the space for political articulation to be occupied by those who really know, the newly angry young activists. In its harsher version, the older critics of the new anger are trounced as everything from right-wing reactionaries to white-loving establishment figures who have done nothing to advance black professors in the academy or decolonise the curriculum or change institutional cultures.

It is worth repeating that what we are witnessing at the moment is a segmented anger, by which I mean not all universities are affected by the new disaffection and that English and Afrikaans universities are affected differently. For example, none of this upsurge of anger has expressed itself in the bureaucratic solidity of the University of Pretoria; it has been for the most part the experience of the old English universities—UCT, Wits and Rhodes. Despite efforts to make RFM a movement rather than an English moment—such as evidenced in the letters from UCT student leaders to SRC leaders on all campuses—the new anger as described has not ventured beyond these privileged sites.

None of this particular brand of criticism, for example, has emerged at the historically black universities where, in some instances, such as TUT, the old struggles of funding access rolls over with predictable regularity in the form of violent protests, and nothing has happened at places like the University of Venda or in institutions where simply meeting the monthly salary bill is the immediate preoccupation.

These basic struggles are light years removed from the new anger that drives the transformation moment at the liberal English universities or that seeks to repel the crude racism and underrepresentation of black youth in the conservative Afrikaans universities.

So in summary, campus struggles are not the same from the English to the Afrikaans to the historically black universities; and the genuine moments of student activism for either access or equity or transformation are often undercut but a destructive violence that threaten to keep our universities in states of turmoil well into the foreseeable future with serious consequences for the academic project.

So what of the future?

There must be a reason the President would set aside time to meet with executive leadership of university councils and university principals. It must be awareness of the fact that if this turmoil continues all universities are at risk. Just as investors do not invest their money in chronically unstable societies, so too top academics do not spend their time on serially disruptive campuses. Parents who have choices send their children elsewhere for higher education, including out of the country, leaving behind moribund institutions where the only students and academics left are those who cannot move. Major foundations and private sector funders of universities and their projects change their investment destinations. The government then becomes involved in trying to shore up these universities and to take control of governance and even management under crisis conditions.

A very good example of how promising universities decline slowly over time as a result of chronic instability is the University of Zimbabwe—they met their “transformation” targets quickly, one could say, but they failed to sustain and build the kind of cultural and intellectual capital necessary for creating top class African universities.

These problems are not insoluble. They can be solved through a different kind of leadership than what the present offers at all levels of our society including government and universities. The students are not the problem; it is how we lead that matters.

In this respect, the white English universities received a necessary wake-up call from their academic smugness reinforced by overseas ranking systems that did not measure institutions on equally important metrics such as social justice and racial integration. The historically Afrikaans universities now realise that they can no longer use this beautiful language as a bulwark against the penetration of black African students in their undergraduate classes—which is the real “site of struggle” in this class of universities.

An important question remains—will the leadership of top universities like Stellenbosch and UCT truly accelerate the deep transformation of their institutions in ways that satisfy the demands of justice? If the leadership of these institutions retreat into their pre-RMF or pre-OSM slumbers, those universities themselves—including councils and senates—threaten the future stability and academic standing of higher education in South Africa. To blame the students, in this case, would be disingenuous.

Which raises the question of the historically black universities in this equation. Here we need to be frank. There has to be a radical new financing model that effectively makes university education free and accessible to all poor students for purposes of undergraduate studies. Until this happens, the chronic violence that keeps so many campuses in turmoil is not going to go away; it is as simple as that. To resolve this matter, governmental leadership is paramount. Simply appealing to students to not be violent, given our history, is not going to make this problem go away. The longer government takes to resolve this matter, the longer black universities will remain mired in sometimes very violent protest cultures.

In the meantime, the historically black universities need courageous leaders who with government support can steer back these institutions into stability so that students are no longer short-changed in the depth and quality of training required for their degrees. Some of these universities are under threat of losing accreditation for some of their qualifications in part a result of the lack of concentrated focus on the academic project. This means disrupting some of the regressive union ‘activism’ on these campuses which with singe-minded salary agendas push universities into financial ruin by holding the academic project and academic leaders to ransom. It also means appointing leaders who can manage with strong, disciplined management teams which can turn around endemic crises within these universities. It means recruiting leaders with political savvy who can anticipate and redirect crises towards positive resolution of staff and student demands.

And it means finding leaders who can win the confidence of students and student leaders by demonstrating through personal example and visible actions that they have gone to the wire for students when it comes to financial, academic and emotional support. Then, and only then, is it possible to require a discipline of student organisation and politics—when an ethic of care and compassion is thread through the management of everyday student life.

Let me say this clearly: in the absence of solving the leadership problem in these universities large injections of state bail-out funding would be a waste of official resources that could have been deployed elsewhere.

If we fail to do this, the South African universities will remain a mirror of the national school system—a small, elite group of functioning institutions which produce the top graduates in the system and a large, chronically dysfunctional set of institutions which remain in a state of stable crisis, surviving from one month to the next without being able to give attention to the academic project. In time, that small elite group of universities will also unthread under the constant stress of student and staff and governmental demands, until they too lose their shine in the international academy and become simply part of an all too familiar post-colonial tale.

It is this felt sense of a present past that Stephen Ellis wrote about and whose warnings we dare not ignore when it comes to the continuities that mark destructive student behaviours on campuses then and now.

Basically you are right. Fees aside, in truth whats the use of education if its empty with no value. Its waste of time and resource. For me the way I trust education I dont wish lack of proper and useful education even to my worse enermy.

As usual the paragon of wisdom, and it comes from a man intimately involved every day at the coalface of higher education and stands consistently on his own two feet in commentary. Make a damn good president of the country, let alone at the helm of a university. That’s not going to happen though, as he’s just not black enough and would never cow tow to any ANC bullshit if he disagreed with the party line.

Sadly, “looking in from the outside”, South Africa is ripening for a second, and this time the “real” revolution. It will be ugly, but as sure as the sun rises in the morning, it is coming. We are all to blame. Whites for our belief that the privileges bestowed upon us by colonialism, and apartheid, are for us to keep and enjoy, and not to share. Our black brothers for electing and unconditionally supporting probably the worst leaders on the continent, if not in the world, to represent them. Then collectively, to allow individuals on both sides of the colour lines, to use race to further their sick agendas.

It is said but very true. I try to be optimistic of a better future where we will choose better leaders but I speak to my brothers and sisters everyday and I fear the worst is to come. Worst leadership is on it’s way to gaining control of the country.

Kovsies are very fortunate to have Prof. Jansen as their VC.

The attitude of ‘holier than thou’ or ‘better than thou’ or ‘whiter or blacker than thou’ will bring us nowhere. The ethic of care and compassions as strongly embedded in Christian values, should indeed be the underlying ethos if we would like, in the long run, survive academic excellency and, at essence, our democracy.

Christian values that you want to impose on others are exactly the ‘holier than thou’ attitude that you are warning us to move away from Kruger. What about the Hindu values? What about Islam, African, Buddhist, etc? Do not bring religion into academic space, unless it is a subject of study.

@ Bolelang.That is not what was said . He said the ethic of care and compassions as – not as only. And how to get to “wants to impose” – he was only referencing.

Wisdom and truth

Thank you. A most interesting discussion. I wonder what your opinion will be of the ‘independant’ universities, with local campus for overseas degrees. How will they assist with change, or will they possibly be the only ones keeping international recognition?

If university education is supposed to be free, what about other levels of post-matric education? We removed the apprentice route, there are no more government training colleges for nurses etc,,

I pity south Africa alot, I remember when Nigeria was having such a problem it was terrible for both the students and the government as we lost valuables academic time

Anger will not get us

anywhere, it is true that the

ruling party, which is

actually the governing party,

is the one promulgating this

anger by charging all their

opponents as agents of

apartheid even black people

like Mmusi Maimane.

This was a brilliant address and really dealt with the nuances of what I saw in the protest. In light of this, I don’t like the way Martin titled it ‘South Africa: when student activism turns to gangsterism’ because that is clearly not the thrust of the article and gives a wholly wrong impression.

unfortunately, Jansen falls into the dualistic paradigm trap, “whiteness v. blackness” ” good leaders v.bad leaders” , ” transformation v. colonialism/liberalism” etc” I respect his attempt to sound a voice of reason, moderation, in short, his sincerity in wrestling with the complexities. The discourse will have to move away from political jargon to facing the practical challenges. Rome was not built in a day, take note!

there is an ancient saying: “whatever is received is received according to the manner of the receiver”

Mandela symbolised the truth embodied in this old saying but it seems he has been trashed as well- s well as see Jansen remarking what the “new anger” says about Mandela.

A little late in the day to be replying to this comment thread, but you mirrored my thoughts exactly Jan. Despite an attempt to sound balanced in his argument, Jansen succumbed to the same old “blame it all on whites’ refusal to transform”. It is some time since so meaningless a term can wreak so much damage.

What you are describing is not unique. You could be describing a woman trying to do business. Or a man becoming a nurse. It’s the way they make you feel, the disparaging looks, the treatment that you are not quite good enough. In each case it is not as if the person made to feel that way is a minority in the population. I think it is more to do with human nature. Mates looking after mates. A network of like minded & like in other attributes looking after their own interests. The best way to get round that is to build your own network. Look after the people & institutions that will build these networks. Or infiltrate the network & transform it from the inside. Trying to hijack or terrorise another group’s network will just create a siege mentality, the more violence the worse it gets.

Jansen’s treatise reminds of a sociological analysis of the present, but with a twist. He is also predictive in his narrative and here he enters a grey area. He imagines the worst. I, however, cannot extrapolate a country’s future by studying a microcosm of that country, ie tertiary education, to form an hypothesis on it’s future. He is somewhat alarmist and tends to generalise the onset of doom. I firmly believe that the goodwill found in average households among common, descent folk outweigh the invective of mayhem and disorder. I remain positive yet not blinkered to the challenges that lie ahead.

As a Brit / Roinek who lived in S africa from 1969 to 1971 I found this sad and disturbing. I worked in exploration and lived illegally in the Richtersveld Coloured Reserve most of the time. My comrades dubbed me Comrade Mike. I was always hopeful but this has dashed all my hopes.

It is to true that there is an anger but the true root of this anger amongst black students towards the white European/Afrikaans clique that runs and sets the standards at these institutions is out of line.There is no true alternative at present and in a multi ethnic world we all have to embrace the differences of other people around us.To much credence is given to the anger young black South Africans feel as I feel this anger is really a flustration to measure up and to be found wanting in their own minds! Europeans exploited this continent but also brought civilisation and progress to this continent!If they stepped on African people in the process,well African people were not the first to face this injustice in the name of progress.To advance or find their place,young black students need to face the truth and forget the summize that is part of the African psyche,namely that there is an African solution to the situation they find themselves in.This situation is quite clearly “pressure” to achieve and make a difference for the better.In today’s world there is no African or European, Asian,or especially American,better way!There is only a human way of doing things and this means where we learn from those who are different to us but perhaps more adapt than us in solving certain of life’s difficulties! Liberalism must be tempered by discipline,self awareness must be tempered by awareness of others,passion or anger must be tempered by reason,otherwise we may as well pick up our weapons and each try to obliterate the reality of the other violently..which is it to be I ask!

Well said! Thanks

A little late in the day to be replying to this comment thread, but you hit the underlying problem on the head, Duncan. It is time black South Africans lost their perpetual identity of victims of previous wrongs and looked at moving ahead in the global sphere … which, as you correctly say, couldn’t be bothered about a person’s race but rather about how well they perform. Entitlement (as we have in our country) does no favours for its recipients in the long term.

I fully appreciate the reflection and the concerns Professor Jansen. I wonder what he would edit in hois reflections, following the recents #feesmustfall movement. I agree that students who are a complex combination of anti white, angry black, and born free beginnings, who raise their intellectual class acess critique and anger, are a cause for concern. But the broader scope of our born frees who are not middle class resourced black Africans must be considered more critically, and cannot be captured as a summary of spoilt black African middle class concerns. In my narrow view of having engaged with campuses by way of my social transformation work, there are many amongst our student populations who are not the spoilt elite black African, but remain concerned and enraged by the lack of integrity of our universities, and are enraged by the continued racialised and systemic social, economic, and intellectual racism that occurs within our academic experience and everyday life. Much more can be reflected upon, but for the sake of the online conversation let me gather my other thoughts as I also consider my role in refraining from fatique of having to exist and go about life vying for work, and opportunity to mobilize one’s ideas in a very racialised social construct of white economic power, control and cultural dominance!

its a little confusing and rambling in my view. And it seems to me to be justifying racism is never acceptable under any circumstance and it should never be tolerated or condoned in this country in any form for any reason. This piece seems to find it acceptable as part of growing. In addition it seems that this is about still looking for the 3rd way, not white, not western still believing the west did nothing for me even though the rest of humanity GOT IT…..good luck with that. When you done, HOPEFULLY the country and its universities will still be standing. if not ZIMBABWE 2 is well on the way. For me the way is beyond race, it is no racial image it is a human progress to attend higher education. Rise above your racism and solve the problems of poverty and higher education, and there are many ways to solve the costs of tuition. This rabble and hooligan behavior is nothing more than an excuse to burn and be racist.

Everyone is entitled to their opinion, but I could disagree with the write to some extent. In any protest, there is no time for tea and cookies. Protests are there to send a clear message. The message that is understood is violence and destruction. To a greater degree, the students and the police tried to a larger extent to exercise restraint in both cases. Everyone was provoked but the marches were peaceful despite there being multiple political factions involved. I comment the students for such moves. I am happy to have been part of this new movement. If the students are termed holigans, does it also mean that the #1976 class Act was an act of hooliganism? I dont think so.

#FEEShaveFallen

#HalloFREEeducation

I didn’t see any anger towards anyone. What I saw was a united South Africa where students joined hands irrespective f racial lines.

Racial discrimination is still hot in some places especially at Rhodes and at the University of Free State.

Well Done Students!

Well done to the 2015 Class!