In theory both the British and the Boers agreed that this would be a ‘white man’s war’. In reality it was nothing of the kind.

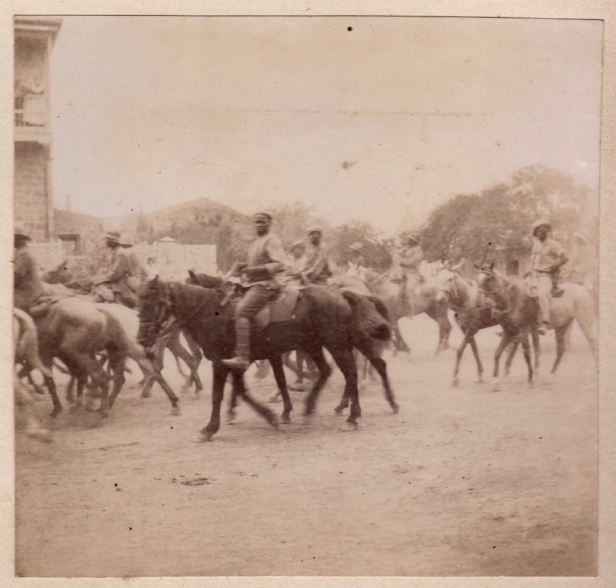

But finding photographic evidence of their role is far from easy. I have some and recently acquired some more. The first two and the last photograph are mine. The photographs from Mafeking are from websites.

They are followed by a short explanation of the role of African and ‘Coloured’ troops in the conflict.

Martin

More frequently, Africans were used as labourers – like this man pictured below

When war was declared between Britain and the two Boer Republics, there was an understanding between them that this would be a ‘white man’s war’ in which black people would not be involved. Under the Boers the African population had few, if any, rights. Yet they had, from time to time, been required to fight alongside their white masters. The Boers had ‘excluded blacks from their state and church, but not from the vitally important institution, the commando, though the Africans that went along were unarmed and served as mere auxiliaries’.[1] Yet the idea that black South Africans would remain as unarmed auxiliaries would soon change, with both sides coming to rely on African and Coloured troops, as well as Indian non-combatants.

In theory the British as well as the Boers rejected the idea that Africans, or even Coloureds or Indians, would play a role in their dispute. The Cape government maintained that arming Africans would create an unfavourable effect on the African population, a stand that was endorsed by the British government.[2] This did not exclude their use as labourers or transport employees, but Africans were not meant to be armed or to participate in the conflict.

When the going got tough, however, it became a very different story. In April and May 1900, during the siege of Mafeking, Colonel Baden-Powell, who was leading the defence, ran out of troops. He had little option but to turn to Africans who had been recruited to dig trenches and act as spies. The Colonel armed 300 Africans, called them the ‘Black Watch’, and gave them the task of manning sections of the perimeter.[3] When his opposite number, General Cronje, discovered what had happened, he was furious. ‘It is understood that you have armed Bastards, Fingoes and Barolong against us,’ he wrote in a letter to Baden-Powell. ‘In this you have committed an enormous act of wickedness … reconsider the matter, even if it costs you the loss of Mafeking … disarm your blacks and thereby act the part of a white man in a white man’s war.’[4]

Even before the war broke out the black population of Mafeking were convinced that they could not escape the conflict. Sol Plaatje, whose diary vividly recorded life during the siege, explained how the Barolong refused to accept assurances that this would be an exclusively ‘white man’s war’. ‘We remember how chief Montshiwa and his councillor Joshua Molema went round the Magistrate’s chair,’ Plaatje later recalled, ‘and, crouching behind him, said: ‘“Let us say, for the sake of argument, that your assurances are genuine, and that when trouble begins we hide behind your back like this, and, rifle in hand, you do all the fighting because you are white; let us say, further, that some Dutchmen appear on the scene and they outnumber and shoot you: what would be our course of action then? Are we to run home, put on skirts and hoist the white flag?” Chief Motshegare pulled off his coat, undid his shirt front and baring his shoulder showing an old bullet scar, received in the Boer–Barolong war prior to the British occupation of Bechuanaland, he said: “Until you satisfy me that His Majesty’s white troops are impervious to bullets, I am going to defend my own wife and children. I have got my rifle at home and all I want is ammunition.”’[5]

In reality blacks had played a part in British defences from the start of the war. The Cape Mounted Rifles, sent to protect the Transkei and East Griqualand, was supported by a Native Affairs Department police force of some 600 men, which contained both African and white policemen.[6] Soon it became clear that such measures would not be sufficient. During the early days of the war the Prime Minister of the Cape, W.P. Schreiner was resolutely opposed to any African participation. As the threat of Boer attacks into the Cape grew, his attitude changed. He relented, allowing the Transkeian forces to ‘defend themselves and their districts against actual invasion’.[7] Milner, as High Commissioner, wrote forcefully that this step was only to be taken as a last resort. ‘What I think about arming Natives is, when we have said “Don’t do it until absolutely necessary” we have said all we can, without unduly interfering with the discretion of the man-on-the-spot.’[8] By December 1899 African levies were being raised all along the borders of the Cape by magistrates for their defence.

Lord Kitchener, who took over as Commander-in-Chief at the end of 1900, had fewer scruples about using black troops. At the same time, he was less than keen to advertise the fact. The Secretary of State for War, William Brodrick, asked for the numbers being deployed, but Kitchener was not forthcoming.[9] When pressed, he finally conceded that 10,053 blacks had been armed. They were used extensively as scouts, guides, dispatch riders, sentries and guards along the vast lines of Kitchener’s blockhouses. This figure is almost certainly a gross underestimate. A further 5,000 to 6,000 men – mostly Coloured – were used as town guards in the Cape alone.[10] Some estimates put the total number of blacks who fought for the British as high as 30,000.[11]

If the British had, somewhat reluctantly, turned to black soldiers to bolster their army, so had the Boers. This was by no means the first occasion on which Boers had relied on Africans to do their fighting. At the time of the Great Trek black servants, ‘Fingoes’ and Bushmen did much of the skirmishing.[12] When the Boer War came, Lieutenant Charles Massey, an intelligence officer with the Grenadier Guards, accumulated ‘evidence of both armed and unarmed natives among our adversaries in the [Cape] colony’.[13] Boer commandos had been observed and ‘all had some natives armed, and on horseback, wearing slouch hats and other Boer clothes … I have always believed what was said of the Boers and their abhorrence of blacks, but now I know better.’

Senior Boer commanders strenuously denied that this ever took place. In early 1902 Smuts assured the strongly pro-Boer British journalist W.T. Stead: ‘The leaders of the Boers have steadfastly refused to make use of coloured assistance in the course of the present war. Offers of such assistance were courteously refused by the government of the South African Republic, who always tried to make it perfectly clear to the Natives that the war did not concern them and would not affect them so long as they remained quiet … The only instance in the whole war in which the Boers made use of armed Kaffirs happened at the siege of Mafeking when an incompetent Boer officer, without the knowledge of the Government or the Commandant-General, put a number of armed Natives into some forts.’[14] But the evidence, assiduously collected by historians like Bill Nasson, points firmly in the opposite direction.

What Bill Nasson describes as ‘fighting retainers’ (or agterryers, in Afrikaans) were widely deployed. Some were captured and interrogated by the British. As one British officer put it: ‘I talked to some of the Boer prisoners and found that there were Coloured men among the Boers, half Dutch, half Native. Also, a goodly number of Kaffirs. The Boers claimed they were only employing black men for digging, driving oxen, etc., but we know that some regularly used rifles.’[15] Another British officer remarked on the camaraderie between the Boers and their African compatriots: ‘I was very surprised at their familiarity with their black comrades … they laugh, talk, eat and joke with them like equals.’[16] Perhaps the exigencies of war had brought together and united bands of men who had come to rely on each other for their lives, and bonds had been formed that cut across the old enmities.

The role of these ‘black Boers’ is captured in this British ditty:[17]

Tommy, Tommy, watch your back

There are dusky wolves in cunning Piet’s pack

Sometimes nowhere to be seen

Sometimes up and shooting clean

They’re stealthy lads, stealthy and brave

In darkness they’re awake

Duck, Duck, that bullet isn’t fake.

[1] Giliomee, The Afrikaners, p. 180. See also Odendaal, The Founders, pp. 21–22.

[2] Odendaal, The Founders, p. 263.

[3] Pakenham, The Boer War, p. 402.

[4] Odendaal, The Founders, p. 264.

[5] Sol T. Plaatje, Mafeking Diary: A Black Man’s View of a White Man’s War, ed. John Comaroff with Brian Willan and Andrew Reed, Meridor Books, Cambridge, 1973, pp. 19–20.

[6] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A Black South African War in the Cape, 1899–1902, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 5.

[7] Ibid., p. 18.

[8] Ibid., p. 18.

[9] Ibid., p. 22.

[10] Ibid., p. 47.

[11] Odendaal, The Founders, p. 265.

[12] Paul S. Landau, ‘Transformation in consciousness’, in Carolyn Hamilton, Bernard K. Mbenga and Robert Ross, The Cambridge History of South Africa, vol. 1, From Early Times to 1885, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, p. 417.

[13] Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War, p. 93.

[14] Ibid., p. 94.

[15] Ibid., p. 97.

[16] Ibid., p. 99.

[17] Ibid., p. 98.

I doubt that there was any formal agreement about Black soldiers – – more likely to have been tacit or individual decisions on both sides … if there was anything at all. It is also more likely that the British colonials would have objected to Black soldiers and Indian soldiers … especially the Natal politicians who were always nervous about armed Zulus.

When, after the War, Chamberlain was asked as Colonial Secretary, how many Blacks the Brit Army used he said of the cuff “30 000” but I doubt that he knew or that the Brit Army knew.

You might read Pieter Labuschagne’s book on the Agterryers.

I think the Black police would have been found in the colonies and the Republics before the war – especially judging by the type of uniform the two are wearing.

When I was in Natal in the 1950s the Durban Borough Police’s Black constables wore a hat not a cap and a dark blue/black uniform with breeches and putties wound round the lower leg – in that climate – with no boots or shoes. The White police wore a black British 19th century style of UK uniform and their officers still had frogging across the chest. In summer the Whites wore white drill tunics. Straight out of Queen Victoria’s wardrobe for the Police.

Please contact me via e-mail: Re Old Photographs

Hello, Martin. I’m writing a book (Reedy Press) and would like to use a photo of Black South African soldiers poising with Blackwatch troops. I saw it on web with your name linked to it. Is it necessary to get your permission for rights? Or is it public domain? Any help would be welcome. Thank you. Patrick Murphy,, St. Louis.

Dear Patrick, you are welcome, as far as I am concerned. The photographs I share I buy on Ebay. But I buy the print. This does not confer ownership of the image. But my view is, what the heck! These images are at least 50 years old. I would use them if I was you. All the best. Martin

Many thanks, Martin, for your quick reply. Much appreciated. Patrick

Hello Martin, I’m making a podcast on the Boer War and would much appreciate including your photo of the ‘Black Watch’. I see from an earlier ‘comment that you buy these image on ebay and you are not the image holder but thought I’d enquire anyway as a courtesy. Thank you.

To be honest, I would go ahead if I was you. The rights expire over time and are by now are unenforceable. If you would not mind, please send me a link to your podcast. All the best

Many thanks, Martin, and will do. Philip