South Africa’s then-president and his cronies devised a plan to build the world’s largest nuclear power plant while enriching themselves greatly. Foreign trips to Russia disguised as medical leave were actually negotiations with Rosatom, making our leaders even more eager to move forward with their plan. They argued that renewable energy was bad for South Africa to get their nuclear agenda passed in the legislature….This meant that no new green power plants were approved while developers continued to pay project site landowners rent in order to secure their rights….By the third year of the freeze, the renewables industry had all but died. Our investors had pulled out, forcing us to close our doors. All of the local manufacturers had shut down their factories and vowed never to commit resources to Africa again.

Source: Mo Ibrahim Foundation

South Africa showcases both the ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’ of building green supply chains

By Nasi Rwigema, MIF Now Generation Network and entrepreneur

In November 2003, the South African government issued a white paper on the role of renewable energy in the future of the country’s energy mix. The report acknowledged the country’s vast sustainable energy resources in the context of its reliance on fossil fuels; it also made a commitment to having 4 per cent of the generation fleet be renewable power by 2013.

By 2009, no progress had been made toward this goal, so the government made the commendable decision to delegate the task to the private sector. Taking after a successful model in Spain, private companies would be allowed to build and own clean power plants and sell the electricity to Eskom, the national power utility.

As a young engineer – just two years into my professional career – I jumped at the chance to co-found a company that would endeavour to build one of these power plants. When the programme was released – regrettably named the “Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Programme (the REIPPP)”- it was designed in a way that seemed burdensome to my team but hugely beneficial to South Africa Inc. because all of the risk was passed on to us.

We would have to find and secure a project site, design and permit the plant, negotiate contracts with construction and operations crews, and raise all the funding. Once we had this in place, we would run our best gymnastics in excel and submit to the government that we believe we can sell them power for x Rands per kWh over a 20-year contract.

The government was shrewd in making this a competitive bidding process, which meant that we had to submit the best price we could muster to outbid all of our competitors. An even more innovative design point of the REIPPP was that our price offer would only account for 70% of the consideration. Commitments to an ‘economic development’ structure accounted for the remaining 30%. This included critical drivers for the creation of local jobs and industries, such as what percentage of the power plant would be owned and operated by black/female/disabled/South African people, as well as similar considerations across the staff who would be hired and the materials that would be procured to build and run the plant. It even accounted for social and business development projects in the communities affected by our massive machines.

The REIPPP was a beautiful programme, thoughtfully designed to create worldclass South African energy companies, hundreds of thousands of skilled local jobs, great new local industries and know-how. Not forgetting, of course, more and clean electricity to the country with little room for public sector corruption. It is worth noting that, at the time, Eskom was six years late and four times over budget on its two most recent coal power plants, and the country was on the verge of rolling blackouts, from which it has still not recovered as of 2022.

So, my team set out to build our first concentrated solar thermal power plant near the Kalahari Desert. We had to hire contractors from Spain, but due to the requirements of the programme, it was easy to persuade them to work with local, black-owned construction companies and hire as many black/female/disabled/ South African people as possible. By early 2013, we had received our first licence, raised $500 million in funding to begin construction, and helped South Africa make a small dent in its green economy plan.

A few years later, we were a leading player on the African energy scene. We had an impressive portfolio of new project developments and an exclusive partnership with a NASDAQ-listed solar panel manufacturer for projects on the continent. The REIPPP had four successful rounds of clean energy procurement and was now producing some of the world’s lowest electricity prices. In its wake, Botswana, Zambia, Senegal, Morocco, and Ethiopia had launched similar programmes. Many component suppliers had established manufacturing facilities in South Africa, and skilled South Africans began taking on leadership roles in several work streams after learning directly from ex-pat contractors.

It was almost as if everything was too good to be true, and that’s when the cracks started to show. Large international energy companies had learned about our programme and, after establishing lavish offices in Cape Town, began winning licences away from South African companies like mine and taking an increasing portion of their economics across our borders. This took the form of fronting, in which the developer provided high-interest loans to local participants. Tracing the actual money flows would reveal that the foreign party owned the construction, the power plant, and the 20-year operation contract. Due to their size and global scale, they were able to negotiate volumes and prices of material components and finance packages that were simply out of our reach. While all is fair in love and war, it was disheartening to see the government stand by while great South African energy companies withered away and sold their projects to the global north for pennies on the dollar.

As the REIPPP’s success grew in prominence, a public debate erupted about the “real cost” of renewable energy, with critics claiming that clean energy was too expensive for the country. They pressed the government on the fact that it was subsidising green energy with higher tariffs than it paid for 30-year-old coal power. In addition, the electricity grid needed to keep backup sources of power because the sun does not always shine, and the wind does not always blow.

The key facts that these detractors ignored were that 1) the country desperately needed more power, and clean power was being added to the grid in 18 months 75 rather than ten years; 2) this is what it takes to create and own something new and strategic; and, most importantly, 3) renewable energy is a crucially good thing for the world, and South Africa was on a smooth path to becoming a world leader in this space.

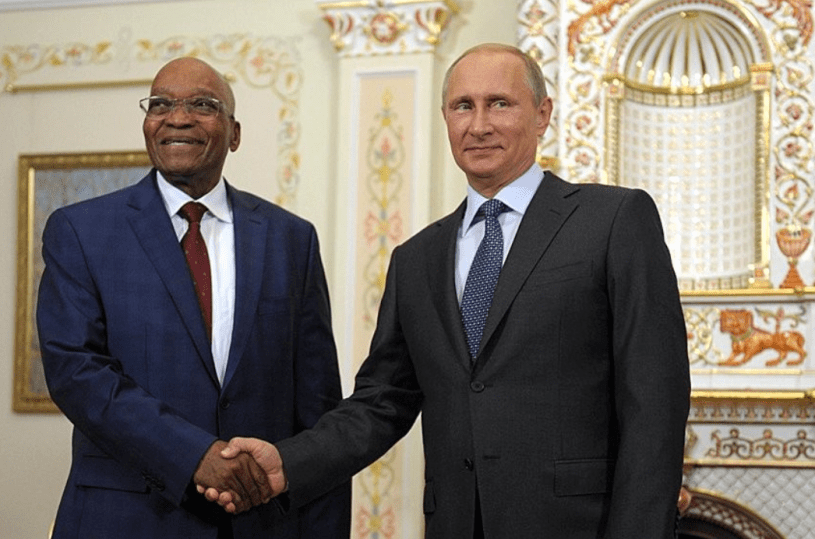

Around this time, South Africa’s then-president and his cronies devised a plan to build the world’s largest nuclear power plant while enriching themselves greatly. Foreign trips to Russia disguised as medical leave were actually negotiations with Rosatom, making our leaders even more eager to move forward with their plan. They argued that renewable energy was bad for South Africa to get their nuclear agenda passed in the legislature, and they managed to halt all further procurement rounds of REIPPP for six years in the process. This meant that no new green power plants were approved while developers continued to pay project site landowners rent in order to secure their rights. Mr Zuma reshuffled government ministers until he had the right pawns in place for his checkmate.

By the third year of the freeze, the renewables industry had all but died. Our investors had pulled out, forcing us to close our doors. All of the local manufacturers had shut down their factories and vowed never to commit resources to Africa again. The skills we had developed as a nation for developing and building sustainable power plants had begun to dwindle as people returned to traditional jobs and industries. Greed and short-term thinking had stifled an exciting opportunity. Along with my own, many hearts were broken, and while the programme is reviving in South Africa today, all necessary trust and goodwill have been eroded, and South Africans remains without electricity for two hours at a time, three times each day.