Eritrea is among the most hermetically sealed nations, with few hard facts emerging to the outside world. No foreign correspondents are accredited to report from Asmara. It has no free press, no Parliament, no independent judiciary and no functioning Constitution. It is a state ruled by just one man: Isaias Afwerki.

However, we do know that that President Isaias is neither immortal, nor is he getting any younger. Born on 2 February 1946 in Asmara (then under British administration) he will turn 80 on 2 February 2026.

Yet, like so many African leaders, he shows no signs of retiring. I assume that he will die post. So, the question arises: what will his legacy be?

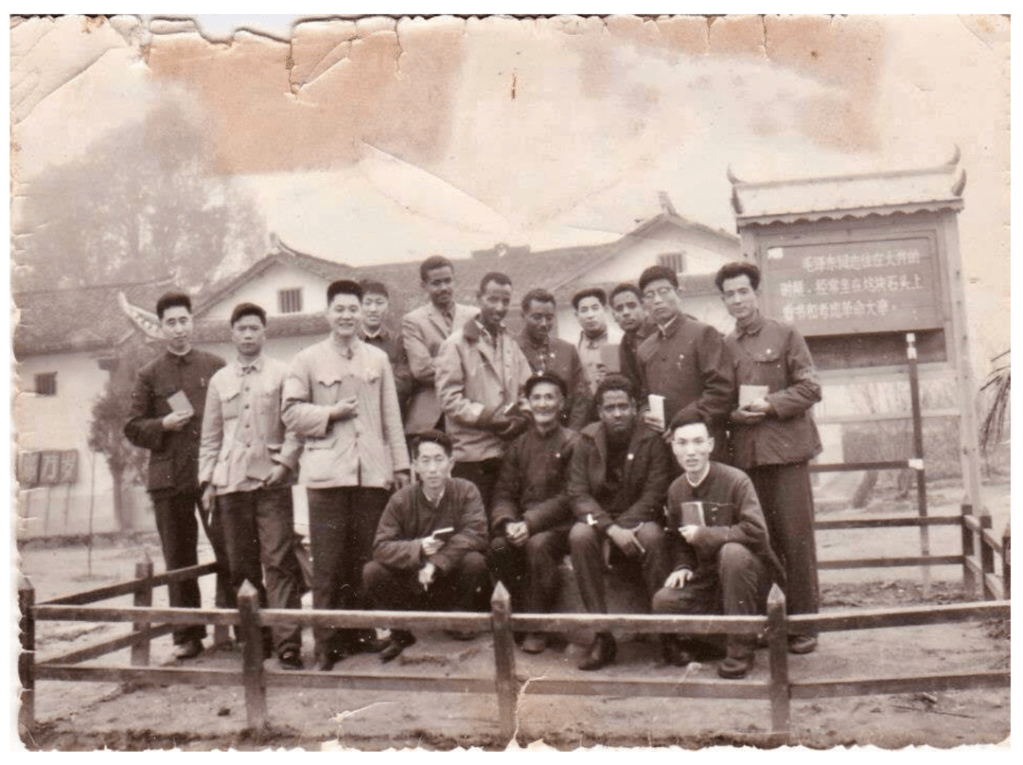

The easiest way to understand this is to remember where Isaias went for his military and political training. It was China, in 1967, at the height of the Maoist repression.

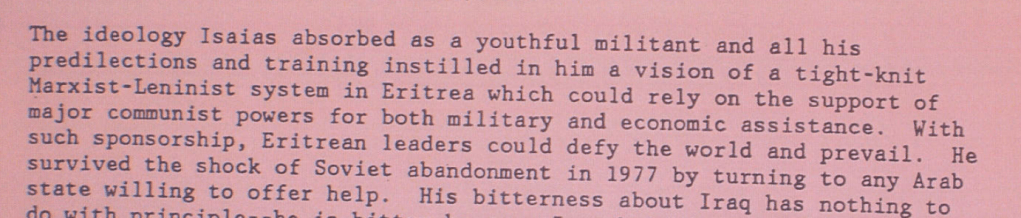

It was here that he learned his Marxism-Leninism, as reflected by the former CIA regional chief, Paul Henze, in the memorandum he sent to Washington on 11 March 1991 about his meeting with Isaias.

It was not for nothing that the Eritrean leader established a secret Marxist-Leninist party that was at the heart of his nations life for decades: the Eritrean People’s Revolutionary Party.

As Dan Connell reported:

“On 4 April 1971, like-minded revolutionaries from the two PLF groups established a secret political formation to rebuild the national movement on a more unified and a more radical social and political basis. Among those at this meeting were Isaias, Abu Bakr Mohammed Hassan, Umero, Ibrahim Afa, Mesfin Hagos, Ali Sayid Abdulla, Mahmoud Sherifo, Hassan Mohammed Amir, Ahmed Taha Baduri, Ahmed al-Keisi and a handful of others. According to Sherifo: We decided to work in a very secretive manner. Marxism would be our leading ideology, and we would call ourselves the Eritrean People’s Revolutionary Party.”

It was the “People’s Party” – as it was called – that ran Eritrea during the war of liberation and for many years after. Isaias led the party, allowing Ramadan Nur to be the figurehead of its public face: the Eritrean People Liberation Front. All resistance during and after the liberation war was ruthlessly crushed.

A militarised society disfigured by ceaseless war

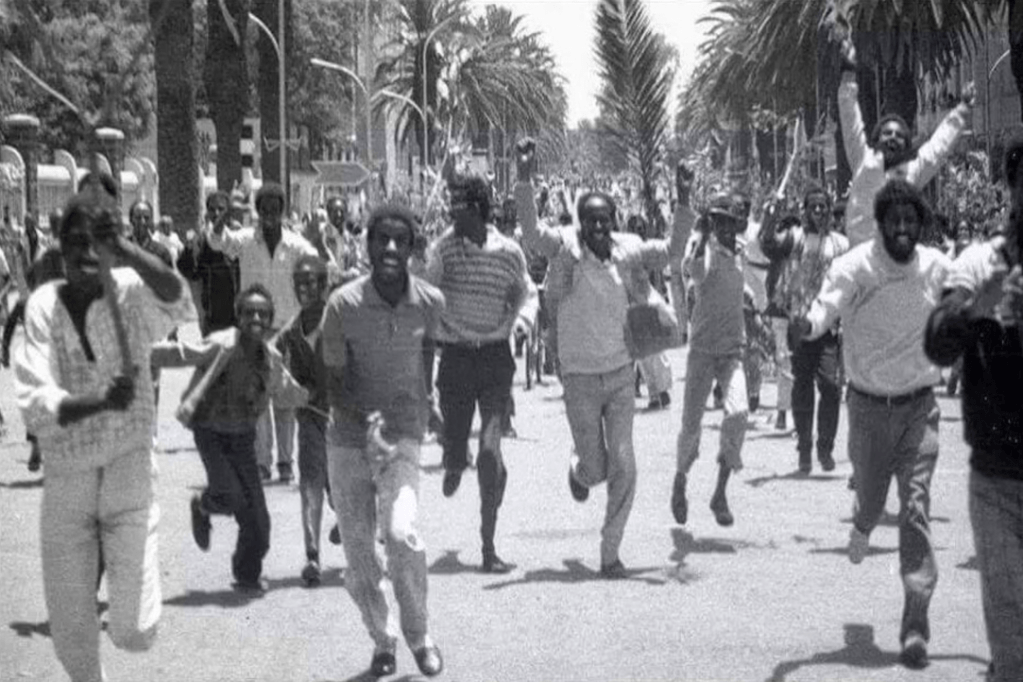

Eritrea is currently at peace. This is something of a novel experience for the country, which fought for its independence so tenaciously from 1961 – 1991, when its troops finally entered Asmara to the jubilation of the population.

Since then, it has been almost ceaselessly at war with its neighbours. The first erupted even before Eritrea achieved its independence in 1993.

Sudan: 1989: This conflict is admirably summarised in African Arguments. Articles by Ahmed Hassan, which can be found here and here, show how Eritrea and Ethiopia worked with Sudanese opposition movements to try to oust the Sudanese government. Sudanese forces were backed by Ugandan troops and American money, in the form of CIA subventions.

Yemen: December 1995: Eritrea fought Yemeni troops for control of the Hanish islands in the Red Sea.

Congo: 1996: Rwanda’s Paul Kagame invaded the Democratic Republic of Congo to overthrow the Mobutu. Eritrean troops accompanied the Rwandan forces, putting in place a Laurent Kabila.

Somalia: 2007: Backing for al-Shabaab after the force was ousted from Mogadishu and the Islamic Courts relocated to Asmara. Eritrea subsequently sent advisers and military equipment to the Islamist group, al-Shabaab, which arose out of the Islamic Courts. As the UN Monitors put it in their 2011 report to the Security Council:

“Asmara’s continuing relationship with Al-Shabaab, for example, appears designed to legitimize and embolden the group rather than to curb its extremist orientation or encourage its participation in a political process. Moreover, Eritrean involvement in Somalia reflects a broader pattern of intelligence and special operations activity, including training, financial and logistical support to armed opposition groups in Djibouti, Ethiopia, the Sudan and possibly Uganda in violation of Security Council resolution 1907 (2009).”

Djibouti: 2008: Clashes with Djibouti. This has spluttered on and off since 2008, leaving the two countries entrenched along their mutual border. In June 2017 Qatar pulled its peacekeeping troops out of the area, leading to fresh tension – which the African Union has attempted to resolve.

Ethiopia: 1998-2000: The border war left at least 100,000 dead and was only ended by the Algiers agreement and the Hague based Boundary Commission ruling should have ended the border dispute, however, Ethiopia refused to accept the outcome, after Badme was awarded to Eritrea. The result was a cold-peace, with forces deployed along the border, until the Ethiopians under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed signed a formal deal in Saudi Arabia with President Isaias, ending the conflict.

Tigray: 2020-2022: This war cost in excess of 600,000 lives. It was the product of a tripartite agreement signed in 2018 between Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia. It ended in November 2022 when agreements were struck in Pretoria and Nairobi. President Isaias declared victory on 31 December, saying “My pride has no bounds…Victory is on our side as we have chosen justice and freedom.”

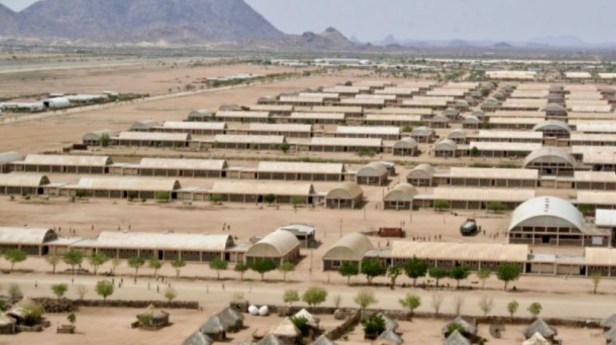

To provide the troops that have been thrown into these conflicts, the President has instituted a system of indefinite conscription. All students must graduate through the Sawa military training camp, and may then spend year after year under military discipline. They may be deployed the borders, sent as teachers to schools or to Eritrea’s mines.

Then – at regular intervals – they are sent to retrain before they are sent to fight in Eritrea’s apparently endless wars against its neighbours, or even further afield.

Rumours and reports swirl that President Isaias has supported Amhara forces since the Tigray war ended, as well as striking a deal with sections of the Tigrayan military. With Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy demanding access to the Red Sea and eyeing up the Eritrean port of Assab, it is far from clear how long peace will hold with Eritrea’s southern neighbours.

An imprisoned society

Without access to an independent judiciary or a right to appeal against arbitrary arrest it is not far from the truth to describe Eritrea as an imprisoned society.

Amnesty International reported in 2024 that:

“Within Eritrea, authorities have been arbitrarily detaining and forcibly disappearing journalists and political dissidents for the past 22 years. They have also discriminated against people based on their faith, denying those from unregistered religions the right to practice their beliefs. According to the UN, hundreds of individuals are currently being held arbitrarily and subjected to enforced disappearances because of their affiliation with unrecognized religious groups. After two decades, the fate and whereabouts of 11 members of the G-15, a group of 15 senior politicians who spoke against the president in 2001, remain unknown, along with those of 16 journalists accused of being associated with the G-15.”

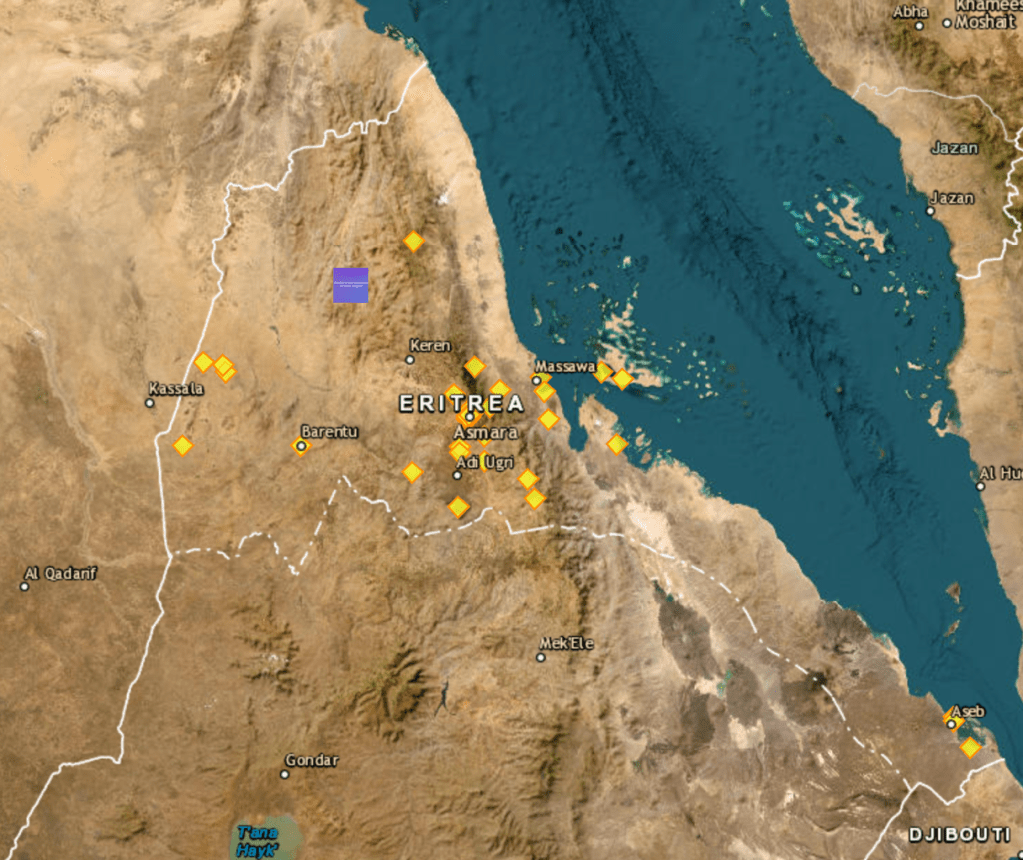

Amnesty produced a detailed map showing the prisons that dot the country.

It is by no means only political prisoners who are detained. Religious groups who refuse to follow the regime’s rules on what may, and may not, be practiced are regularly rounded up.

In his May 2025 report A/HRC/59/24, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Eritrea, Mohamed Babiker, said that he was:

“…particularly concerned over the prolonged arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance of religious leaders and people of faith, some of whom have been detained for over 20 years without having ever been charged with or convicted of any crime. As at April 2025, 64 Jehovah’s Witnesses and an estimated three hundred to five hundred evangelical Christians remained arbitrarily imprisoned without charges or trial. As a result, members of unrecognized religious groups live in fear of being caught in worship, or of their faith being discovered.”

The Special Rapporteur went on to discuss how the “government sought to control all religious communities and institutions, both within the country and in the diaspora.” Religious schools have been taken over, and the government now also controls the Orthodox Church.

“In the case of the Orthodox Church, the removal and placement under arbitrary house arrest of Patriarch Abune Antonios in 2006 by the authorities generated a rift between religious leaders and members of the Church who followed Abune Antonios and those who followed the government appointee, Abune Dioskoros. Following the death of Abune Antonios in 2022, the divisions deepened as his followers were persecuted. As at April 2025, it is estimated that more than 100 Orthodox priests, monks and followers of the late Patriarch remain imprisoned. On 26 January 2025, the Asmara Synod, reportedly controlled by the Government of Eritrea, installed a new patriarch, Abune Basilios, with the participation of representatives of the Coptic, Armenian, Indian and Syriac Orthodox Churches. Eritrean faith leaders in the diaspora denounced their exclusion from the selection process for the new patriarch.”

Life for ordinary people

It is no exaggeration to say that for many time has stood still, in terms of economic development. Apart from a handful of mines, most men and women must live from agriculture or small-scale trading.

Ethiopia has significantly outperformed Eritrea in economic growth since 1991, driven by economic liberalization, agriculture, and services, while Eritrea’s growth stagnated due to war, isolation, and sanctions. Eritrea averaged 4.66% annual GDP growth from 1991-2024, peaking at 21.25% in 2001 but falling by -13.12% in 2000 during the conflict with Ethiopia. No-one can be certain: no national budget is published and the state of the nation’s resources are little understood.

Every aspect of life is controlled: it is impossible to even carry out repairs on your home without permission from the authorities. In Asmara water and electricity regularly fail. Access to the internet is strictly restricted. Life is one of drudgery – day in and day out. There is little prospect of change or amelioration.

Is it any wonder that so many decide instead to flee abroad, even though this can be immensely dangerous. Many leave their bones in the Sahara or are captured and sold into slavery in Libya. Others die crossing the Mediterranean. Yet still they take the terrible risk.

A nation in exile

It is hardly surprising that Eritrea’s population of 4 – 5 million (there has been no recent census) is less than willing to live under such repressive conditions.

As the UN Special Rapporteur told the UN:

“Eritreans continued to flee the country, driven by persistent human rights violations. As at June 2024, Eritrea ranked as the tenth-largest country of origin for refugees and asylum- seekers globally, with over 683,000 individuals, or 18 per cent of its population, having fled the country according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).”

Even when they manage to establish a life abroad, Eritreans are subjected to Transnational Repression.

The UN Special Rapporteur explained what the situation was like in a variety of nations, starting with Ethiopia.

- Hundreds of Eritreans, including dozens with refugee documentation, were detained in police stations across Addis Ababa without charges or due process. In many cases they were held for several months in facilities designed only for short-term detention, in harsh and overcrowded conditions, with insufficient food.

- Egypt also continued to detain Eritrean refugees and asylum-seekers for prolonged periods and to forcibly return them to Eritrea. This included individuals registered with UNHCR, long-term residents with established legal status, and parents, who became separated from their children.

- On 6 August 2024, Turkey deported 203 Eritreans to their country of origin.

- The Special Rapporteur is gravely concerned about the situation of Eritrean refugees and asylum-seekers in Israel, where the prolonged lack of access to legal status and basic rights and services has led to a de facto segregation of Eritrean asylum-seekers from Israeli society.

Even when they arrive in Europe of the Americas, Eritreans continue to be subjected to pressure to provide financial and political support for the regime they have fled from. Sometimes this turns violent.

As Mohamed Babiker reported:

“The Government continued to employ an array of coercive strategies to enforce loyalty and supress dissent within Eritrean diaspora communities. The Special Rapporteur continued to document instances of transnational repression, including surveillance, harassment, threats, physical assaults, punishment by proxy – whereby the families of dissenters are targeted inside Eritrea, smear campaigns, social isolation, censorship and denial of consular services.”

From Norway to Britain, from Germany to Canada, Eritreans are subjected to these pressures by the regime, its diplomatic agents and supporters to try to bring them into line.

So what is Isaias’s legacy?

On the plus side, Eritrea has remained an independent nation, despite its many wars. It is resisting the continuing threats from Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to fight his way to the sea.

“Abiy and army chief Field Marshal Birhanu Jula have openly claimed ownership of Eritrea’s southern port of Assab – about 60km from the border – and hinted at the desire to take it by force. On 1 September, Abiy said Ethiopia’s “mistake” of losing access to the Red Sea as a result of Eritrea secession would be “corrected tomorrow”. Ethiopia’s ambassador to Kenya, retired Gen Bacha Debele, said that Assab was “Ethiopia’s wealth” and would be returned “by force”. “The question now is not whether Assab is ours or not, but how do we get it back?” Ambassador Bacha told pro-government YouTube Channel Addis Paradigm on 3 November.”

The Eritrean military is currently subservient to the President. It has shown no sign of resistance since 2013 and the “Forto mutiny”.

Isaias has managed to keep his senior officers subdued by repeatedly purging them, moving them from one command to another and by relieving them of their commands.

Despite this, the army remains the one institution capable of taking control of the nation when the President finally dies. Whether they can remain united, or whether senior officers resort to force to settle their differences, is the major unknown.

How they, or anyone else, will be able to rebuild the traumatised population is difficult to predict. Many national assets are held abroad, often in private hands. Few outside President Isaias’s immediate circle know who has control over them.

However, Eritreans are remarkably resilient. Many have made good lives abroad for themselves and their families. They could be persuaded to use their assets and talents for the benefit of the nation – if the circumstances were right.

It’s people are also patriotic, even those who loathe the current regime. With their skills, passion and energy Eritrea could truly become the nation so many have dreamed of for so many years.

you privide data and you contradict it right there by saying there is no official report. You compare it with Ethiopia but Ethiopian’s for sure know their life is not any better. Its all in vain my friend.

The fixated nature of this analysis is troubling. It is difficult to understand why an outsider would focus so intently on the demise of a head of state, almost as if they are anticipating it.

To suggest there is no succession plan underestimates the administration. Given the President’s long tenure, it is far more likely that he and his cabinet have a strategic transition plan in place. The constant ‘trashing’ of Eritrea by certain foreign analysts raises questions about their true motives and whether they are serving specific interests. Finally, we should look at the success of one-party systems elsewhere China is a prime example of how such a model can lead to immense national progress and stability. It proves that Western-style systems are not the only path to success

Tell me Tesfay, what did China established within 35 years and what did Eritrea achieved in the same period.

Thank God President Isaias is not immortal! What a disgraceful human being he is, an absolute criminal. His death is the only hope for the poor people of Eritrea