Mulugeta Gebregziabher, PhD

The catastrophe at Hitsas Internally displaced people (IDP) camp exposed a system that reacts only to shame, not to suffering. With hundreds of thousands still displaced across Tigray, the next Hitsas is already forming. The way out is decisive reform of the Tigray Emergency Response, local accountability, adopting the US’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) style emergency response structure and a diplomatic strategy that compels global action.

A crisis that did not “happen”, but allowed to happen

The tragedy at Hitsas was not a bolt from the blue. It was deliberately created by the Abiy regime and the foreseeable result of institutional paralysis, weak monitoring, and late, performative reactions. Region‑wide data confirm the depth of displacement and need: Tigray hosts over 760,000 IDPs (Ethiopia’s total is ~1.9 million), most displaced by conflict; protracted displacement remains high and returns are limited.[1-2] UN analyses in mid‑2024 already warned of 4.5 million people displaced nationally with Tigray among the top regions of concern.[3] This is a system that knew and still failed to act. It was Abergele in 2024. Yakir and 70 Kare in early 2025 and now it is Hitsas.

Studies indicate that nearly 50 percent of all reported deaths in Tigray are due to starvation, most of them among IDPs. A study covering the November 2022–August 2023 found that starvation was the leading cause of death across all age groups, accounting for 49.3% of verified deaths. Children under five and women were among the most vulnerable. The same is true with new HIV infections and other communicable diseases.

Hitsas is a warning, not an outlier

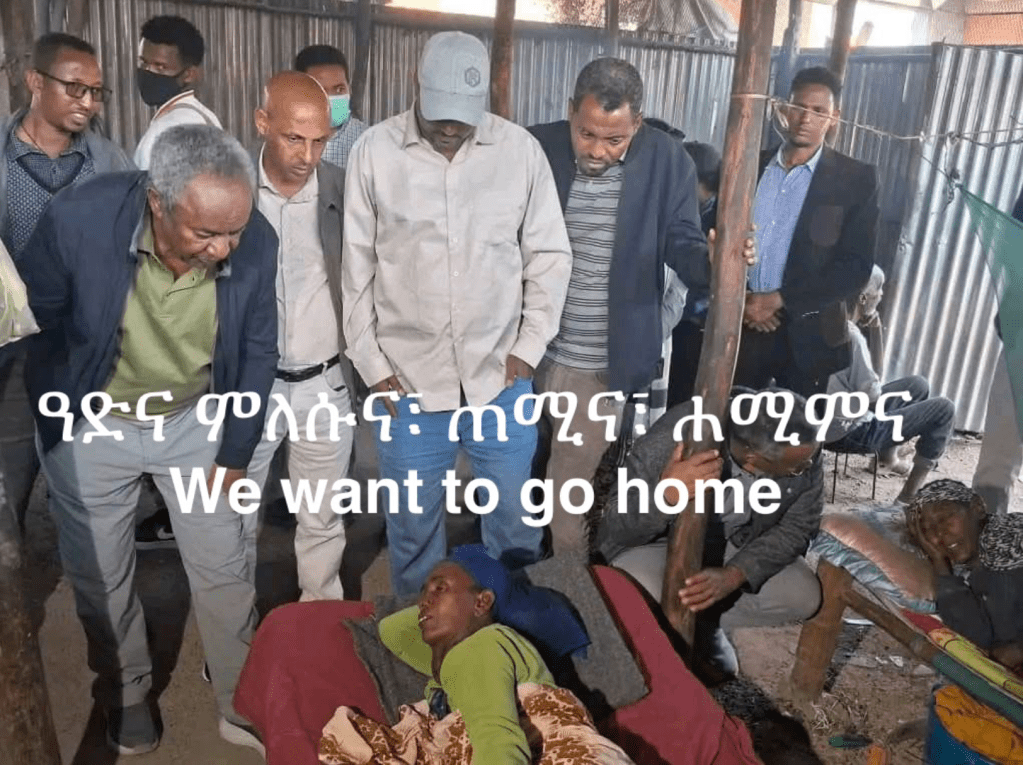

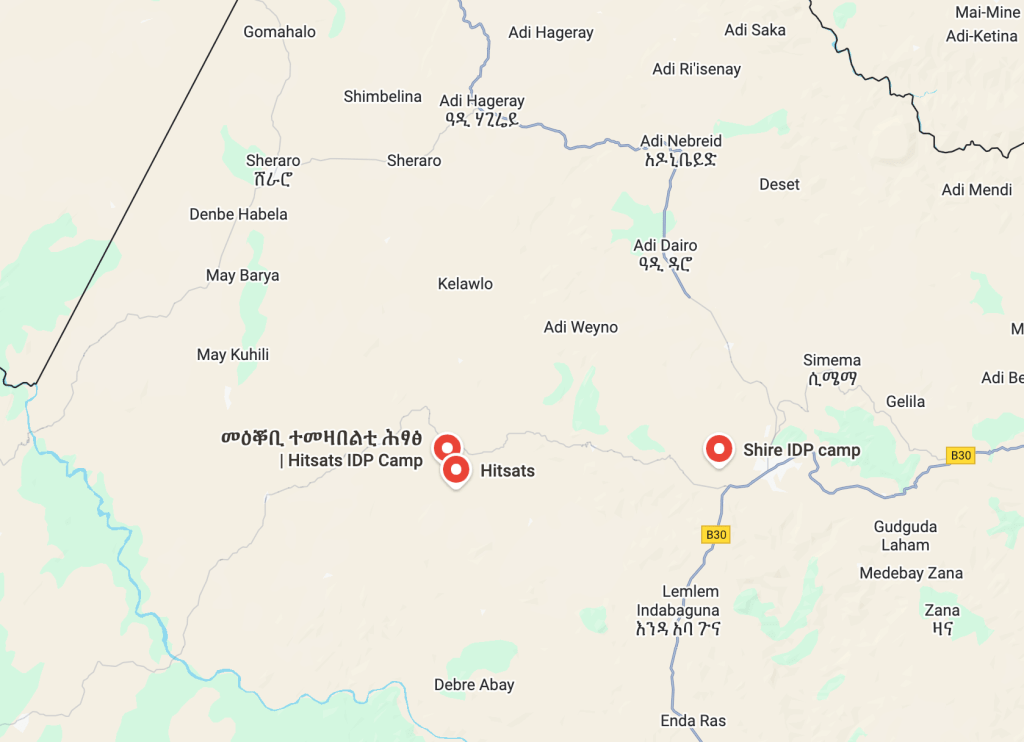

Unpublished investigations and local reports indicated that over 300 IDPs have died from starvation and lack of medical care at Hitsats IDP Camp in Northwestern Tigray since 2022. Since July 2025 alone, more than 50 additional deaths have been reported, placing thousands more lives at immediate risk. Meanwhile, a dramatic cut in humanitarian aid has deepened the crisis. It is reported that food assistance dropped by 56.2%, from 1,657,018 people in January 2025 to just 725,839 in November 2025, mostly IDPs. This means almost a million fewer people received life-saving support in just eleven months.

Comparing Hitsas with camps in and around Mekelle makes the point painfully clear. MaiWoyni (Hadnet School) in Mekelle is one of 26 IDP sites in the city, with nearly 200,000 displaced people citywide and 7,000+ in MaiWoyni alone.[4] A multi‑agency assessment across Mekelle and Enderta documented severe shortfalls in food, water, health services, essential non‑food items, and Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) conditions that deteriorate as the crisis drags on.[5] Independent analyses found acute malnutrition soaring across Tigray: severe acute malnutrition in children at ~6% (versus 1% pre‑war) and moderate acute malnutrition ~22%, with water scarcity compounding disease risk.[6] In August 2025, Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and partners verified that the Global Acute Malnutrition of 62% in parts of Kola Temben and reported cholera outbreaks in Selewa and Samre; 5,200 shelters were destroyed by flooding with zero in‑country replacement stock.[7] These facts say what headlines don’t: the next Hitsas could be anywhere. It could be any of the dozens of understaffed, under-resourced, and unmonitored camps across Tigray. What is uncovered in Hitsas is systemic, widespread, and deepening.

Good hearts, slow institutions and a short public memory

Ordinary people responded to Hitsas immediately, sharing scarce food and mobilizing community solidarity. Institutions, by contrast, disappeared into meetings and travel itineraries. Starting from April 2025, there was warnings that funding shortfalls, political instability, and delayed returns would prolong needs and constrain operations in Tigray; more than 2.5 million people were expected to face food and nutrition needs, with 500,000 at critical levels.[8] Even as UN OCHA flagged rising tensions and outbreaks through 2025, the cadence of official action remained sporadic, reactive, and under‑resourced.[9] When leaders respond only after public shame, they are not leading; they are managing optics.

Universities: A Promise or a Missed Opportunity?

The involvement of the four universities in responding to the public outcry is a welcome gesture. But gestures alone cannot feed a child, cannot heal a mother, cannot rebuild a life. Carrying bags of food is not enough. Universities must do what universities are meant to do: generate data, produce solutions, train responders, design long-term strategies, hold institutions accountable through research and public engagement. If their participation ends at short-term donations, they will simply become part of the cycle of reaction rather than prevention. If Hitsas had not gone viral, would any of these universities have responded? The painful answer, judging by history, is likely no. The participation of Tigray’s universities must shift from symbolic food drops to strategy and stewardship. Their comparative advantages are data, design, and training: real‑time camp monitoring, early‑warning nutrition and WASH dashboards, responder training, and independent policy evaluation. Done right, universities become solution architects, not just donors of grain. [5, 8]

The Deafening Silence of the World: UN, WHO, and the Double Standards

Perhaps the most painful dimension of this crisis is the indifference or, at best, the inconsistency of the global humanitarian establishment. Global actors acknowledge the emergency but act unevenly. UN OCHA communications have verified extreme malnutrition, cholera outbreaks, and shelter destruction across Tigray, yet the scale of surge support remains inconsistent with the indicators. [7, 9] WHO and health cluster partners note outbreaks and shortages, but public advocacy rarely matches the gravity of the situation on the ground. [7] This raises fair questions of institutional consistency:

- Why does WHO’s global voice boom for some crises yet remain muted for Tigray’s IDP catastrophe? I would be happy to know if there have been voices made in the last two years, especially in the last 9 months.

- Why did the son of Tigray, Dr Tedros, choose to be silent on Tigray compared to other crises?

- Are political sensitivities eclipsing equity of alarm when the data demand a louder response?

These are not personal accusations; they are calls for transparent standards that treat equal suffering with equal urgency. [7,9]

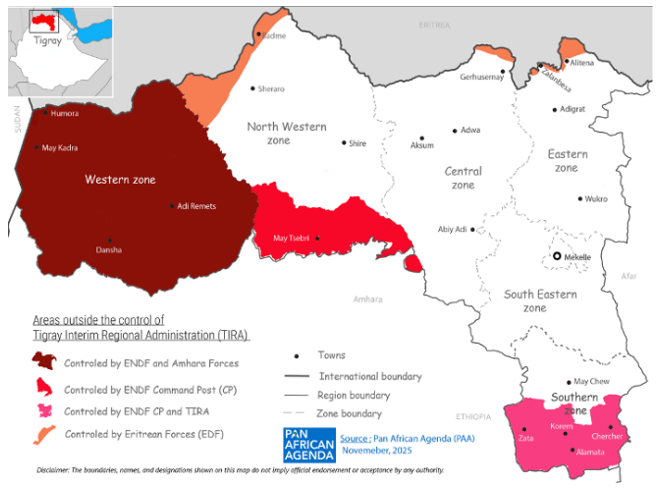

A region forced to speak for itself

The Hitsas episode also revealed a diplomatic vacuum. Ethiopia’s federal government holds the constitutional remit for foreign relations yet has failed to adequately represent Tigray’s humanitarian needs to donors, UN agencies, and the global public. The result: no sustained corridors, weak visibility, limited monitoring, and politicized access. When the state that should speak for you does not, silence becomes a weapon and civilians pay the price. There are credible reports of escalating obstruction including the confiscation of publicly collected aid for Histas victims at airports and transport hubs, which is also corroborated by official government statements. In its most recent statement, the Disaster Risk Management Commission has threatened individuals collecting assistance to Tigray IDPs to stop or face legal consequences. Surprisingly without shame, the commission states that food distributions to sites such as Hitsas have continued “in full and without interruption” between September and December 2025. This official position stands in sharp contrast with reports of confiscated supplies and threats of legal penalties against citizens collecting aid for displaced Tigrayans actions that, if verified, would constitute not only a violation of humanitarian norms but a punitive approach toward public solidarity itself. This is pure case of gaslighting and flagrant violation of humanitarian laws but also mean spirited.

Why Is the IDP Crisis Across Tigray Being Ignored?

This is the most frightening question of all. Because what happened in Hitsas was not unique. It was simply the first camp whose suffering became visible. As reported by the UNHCR in April of 2025, the humanitarian situation in Tigray is dire, with 760,406 internally displaced persons (IDPs) living in precarious conditions across various sites. Many IDPs are forced into overcrowded collective centers due to dwindling resources and overcrowding, facing severe food shortages, inadequate access to clean water, and insufficient medical care with preventable 325 deaths documented at the Hitsats IDP Center alone in 2025. The situation is exacerbated by the lack of humanitarian assistance, with food distributions often falling below humanitarian standards. These 760 IDP camps are the next Hitsas. Unless something changes, we will mourn again.

The way forward: adapting FEMA’s Emergency Management Framework for Tigray and Other Resource‑Limited, Conflict‑Affected Regions

The below provides a practical, scalable framework, modeled on U.S. FEMA, that Tigray and similar regions can adapt for effective disaster preparedness, response, accountability, and community participation. To create parallels between the administrative organization of Tigray as a state to adopt the FEMA response, we will use the following (Tigray = Federal level, Zones = States, Woredas/Towns = Counties/Municipalities).

Tigray Emergency Management Agency (TEMA)’s mission is helping people before, during and after disasters. TEMA should have an agile governance structure that quickly responds to crisis with program and Woreda level offices located throughout Tigray. A central TEMA office needs to be created to provide policy direction, coordination, resource allocation, and financial accountability at the region level.

- Zone Emergency Management Offices (ZEMO) coordinate multi‑Woreda operations.

- Woreda Emergency Management Offices (WEMO) lead frontline response, rapid assessments, and incident management.

- A simplified Incident Command System (ICS) ensures unified command, common terminology, and coordinated operations across NGOs, health facilities, and community groups.

Activation, Recognition & Funding Flow

- Rapid Impact Assessment (24–72 hrs) from Tabias to Woredas to Zones.

- Verification and National Emergency Declaration by TEMA.

- Tiered funding phases: Phase 1: Immediate life‑saving assistance. Phase 2: Stabilization and essential services. Phase 3: Recovery and reconstruction, linked to verified outputs.

- Tiered funding phases: Phase 1: Immediate life‑saving assistance. Phase 2: Stabilization and essential services. Phase 3: Recovery and reconstruction, linked to verified outputs.

Monitoring, Reporting & Verification (MRV)

- Triangulated reporting using community verification groups, and NGO situation reports.

- Random field audits by Zone and Regional auditors.

- Public transparency portals with spending summaries and project progress.

- Independent oversight board composed of academic, faith‑based, and civic institutions.

Financial Controls & Anti‑Corruption

- Ringfenced bank accounts with standardized financial ledgers and three‑signature authorization.

- Open procurement with conflict‑of‑interest declarations including whistleblower protection, anonymous hotlines, and mandatory grievance resolution.

- Quarterly public expenditure reviews with community hearings.

Role of Charities, Churches, and Individuals

- Charities: They should be pre-registered, willing to data‑sharing, & safeguarding compliance.

- Churches: Could create aid distribution hubs, provide or facilitate psychosocial support centers, and get involved as trusted community oversight.

- Individuals/Diaspora: They should be able to use verified channels; support local procurement and cash‑for‑work programs; avoid unverified distribution chains.

Community Training: Building Understanding & Ownership

For effective adoption, communities must understand the process, benefits, and responsibilities of emergency management with the new TEMA structure.

- Workshops at Woreda level on early warning, reporting procedures, and aid eligibility.

- Public communication tools: Radio/TV/Social media messages and illustrated guides explaining the response cycle, rights, and complaint mechanisms.

- Community volunteer corps: Youth/women’s groups and community representatives trained in safe distribution, hazard assessment and participation in oversight.

Metrics for Success & Accountability: to ensure measurable effectiveness, the system should track metrics that allow continuous improvement, public trust building, and donor confidence. The operational metrics could factor the following:

- Assessment speed: % of Woredas submitting Rapid Impact Assessments within 72 hours.

- Response speed: Time from NDA declaration to first delivery of life‑saving aid.

- Coverage: % of affected population receiving assistance within defined timelines.

Financial Accountability Metrics

- Audit compliance rate: % of Woredas and Zones passing quarterly audits.

- Procurement transparency score: % of contracts awarded through competitive processes.

- Leakage indicators: Ratio of accounted resources to distributed resources.

Community Engagement Metrics

- Training coverage: Number/percentage of households reached with prepared education.

- Complaint resolution time: Average days to resolve grievances.

- Participation: Attendance rates at community oversight forums.

Call to Action: Reforming the Tigray Emergency Response Commission with the above proposed TEMA structure is action that needs to be taken as soon as possible. It is time for the Tigray Interim Regional Administration (TIRA) to lead the reform of TER into a modern, FEMA‑aligned institution, TEMA. A reformed TEMA will dramatically strengthen preparedness, rapid response capacity, accountability, and community trust, ultimately save lives and accelerate recovery.

The diplomatic route for a life‑saving action

Tigray’s administration should open its own humanitarian diplomatic channels, formal and informal, focused strictly on protection, relief, and rights. This is not about sovereignty; it is about survival and the globally accepted practice of sub‑national engagement in extreme crises.

Seven steps Tigray can initiate immediately:

- Appoint a Humanitarian Envoy empowered to engage UN agencies (OCHA, WHO, UNICEF, IOM, WFP), African Union, and major donors on access, supplies, and monitoring.

- Publish weekly multilingual situation bulletins (nutrition, WASH, outbreaks, protection) using standardized indicators; invite third‑party verification by universities and NGOs.

- Convene a quarterly donor roundtable in Mekelle, cohosted by universities, to align funding with verifiable needs and publish commitments and delivery against targets.

- Negotiate neutral humanitarian corridors with other counterparts and international guarantors, document every obstruction and escalate through OCHA and AU mechanisms.

- Sign MoUs for independent camp monitoring with institutions such as the International Office of Migration Displacement Tracking Matrix (IOM‑DTM) and research institutions to track returns, relocations, and integration outcomes.

- Activate an Outbreak Escalation Protocol with WHO and partners to fast‑track cholera, measles, and malnutrition responses within 72 hours of threshold breach.

- Use diaspora networks for strategic advocacy, brief missions in Geneva, New York, Washington DC, Brussels, Nairobi; seek special sessions, briefings, and field visits focused on Tigray’s IDPs.

Accountability at home, credibility abroad

Diplomacy will only work if Tigray’s institutions prove they can deliver. That means installing a real‑time camp monitoring system with public dashboards; creating independent investigative panels for preventable deaths; and setting a rapid‑response command center for food, health, WASH, and protection. The people have shown their heart. Institutions must now show competence.

The Promise- never again, not anywhere in Tigray

Hitsas must become the benchmark for “never again.” Every delay breeds the next disaster; every unmonitored camp is one missed warning away from tragedy. Tigray cannot survive on charity and outrage cycles. It needs leadership that anticipates, universities that design, and diplomacy that compels.

Because unless the system changes, the next Hitsas is already here.

Accountability and the Short Memory That Enables Impunity

The tragedy of Hitsas is more than starvation, disease, and preventable deaths. It is a mirror held up to a system that is failing its most vulnerable. The failure was not sudden. It was not unpredictable. It was the result of institutions that do not monitor conditions, leaders who do not act in time, and humanitarian bodies whose presence has become symbolic instead of life saving. Yet, amid the institutional paralysis, there was something else, something else something powerful. The people of Tigray responded instantly. They shared what little they have. They organized, mobilized, carried food on their backs, and reminded the world that solidarity is still alive here even when state structures go quiet. This duality, the goodwill of ordinary people versus the lethargy of institutions, is tearing Tigray apart.

There is a painful pattern emerging in Tigray: A crisis unfolds, a handful of individuals raise the alarm, institutions deny, delay, or disappear into endless meetings, public outcry erupts, leaders rush to make a “showing.” The moment passes and accountability evaporates.

This short public memory allows those responsible for negligence to rebrand themselves as saviors once the damage is already done. They step forward only after community pressure forces them to. They hold meetings only after public shame makes silence impossible. This is not leadership. It is survival politics.

And it is dangerous, because it guarantees that new crises will emerge, repeatedly, with the same deadly consequences.

Where Are the Institutions Built to Protect the Vulnerable?

Tigray has offices specifically mandated to monitor displacement, coordinate humanitarian response, and plan durable solutions. But Hitsas revealed a devastating truth: these bodies are not monitoring, not coordinating, and not solving. They are meeting. They are traveling. They produce minutes, not outcomes. When institutions behave like this, humanitarian crises do not develop, they metastasize.

Hitsas must not fade from memory. It must become the benchmark against which we say: Never again in Tigray. The people have shown their heart. Now institutions must show theirs.

About the author.

Mulugeta Gebregziabher (PhD) is a Peace Laureate of the American Public Health Association and a tenured professor at the Department of Public Health Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, USA. He is a peace and justice advocate who also contributes viewpoint articles on the current crisis in the horn with focus on Ethiopia. Views are his own. Mulugeta can be reached at his X: @ProfMulugeta or e-mail: mulugeta.gebz@gmail.com

References

- UNHCR / DTM, Ethiopia Refugees and IDPs statistics (Feb. & Jun. 2025) — national and regional IDP figures; Tigray share and conflict drivers.

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2122834/Ethiopia+Refugees+and+IDPs+statistics+February+2025.pdf - UNHCR Operational Data Portal, Ethiopia | Refugees and IDPs statistics (Jan 2025).

https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/114651 - UN OCHA, Internal Displacement Overview (June 2024).

https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-internal-displacement-overview-june-2024 - African Services Committee, Displaced in Mekelle—May Woyni IDP Center.

https://africanservices.org/displaced-in-mekelle - Tigray Regional Health Bureau & Project HOPE, Multi‑Agency Rapid Needs Assessment for IDPs in Enderta & Mekelle (Apr 4–8, 2023; published 2024).

https://www.projecthope.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Multi-Agency-Rapid-Needs-Assessment-Report-Tigray_2023.pdf - Modern Diplomacy, The Plight of Internally Displaced Persons in Tigray (Feb 27, 2025).

https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/02/27/the-plight-of-internally-displaced-persons-in-tigray-a-humanitarian-crisis/ - ReliefWeb / ECHO Daily Flash (Aug 14, 2025): Malnutrition, cholera and IDP situation in Tigray; shelters destroyed and no in‑country stock.

https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-malnutrition-cholera-and-idp-situation-tigray-dg-echo-un-ocha-partners-acf-ethiopian-red-cross-society-echo-daily-flash-14-august-2025 - FSCluster / ACAPS Analysis Hub, The Humanitarian Situation in Tigray Region (Apr 8, 2025).

https://fscluster.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/The%20Humanitarian%20Situation%20in%20Tigray%20Region.pdf - UN OCHA, Ethiopia: Humanitarian Update (Mar 27, 2025).

https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-humanitarian-update-27-march-2025 - ODI–HPG, The lives and livelihoods of urban IDPs in Mekelle (Dec 2024).

https://media.odi.org/documents/Ethiopia_case_study_final.pdf - IOM, Ethiopia Crisis Response Plan 2025 (Feb 7, 2025). DTM IDP/returnee figures. https://crisisresponse.iom.int/response/ethiopia-crisis-response-plan-2025

- Mekonnen Haileselassie et. al. (2024, December 18). “Starvation remains the leading cause of death in Tigray, northern Ethiopia, after the Pretoria deal: a call for expedited action.” BMC Public Health. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-209329

- DW Interview with Prof Mulugeta Gebregziabher (2025). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZTc6jzkgqg&t=1s

- Mache Tsadik, …, Mulugeta Gebregziabher (2024, October 16). “Armed conflict and maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region: a community-based survey.” BMC Public Health. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-20314-1

- Le Monde (2024). Famine in Ethiopia’s Tigray has become a political battle. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/03/11/famine-in-ethiopia-s-tigray-has-become-a-political-battle_6607766_4.html

- Emma Ogao. (2024). “Ethiopian prime minister dismisses reports of famine deaths.” ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/International/ethiopian-prime-minister-dismisses-reports-famine-deaths/story?id=107016186. February 7, 2024.

- Tigray Bureau of Health and Tigray Nutrition Cluster. Tigray region findings from SMART Survey. July-August 2024. https://fscluster.org/sites/default/files/documents/tigray_smart_surveys_pooled_report_aug_2023.pdf

Well explained report with detailed analysis and insightful way forward!