This article, by Professor David Killingray, not previously published, gives a fascinating insight into the fate of slaves freed by the Royal Navy in the Indian Ocean – many of them Oromo being taken by dhows to be sold in the slave markets of Arabia.

Martin

Rev James Challa Salfey

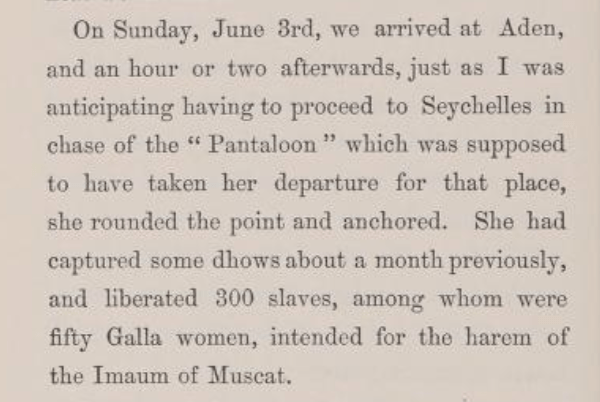

Challa Salfey, an Oromo (then referred to as ‘Galla’) originally from what is now southern Ethiopia, as a child of seven was rescued from a slave dhow in the Indian Ocean intercepted by the British warship ‘Pantaloon’.[1]

Salfey’s account of his path to slavery echoes that of other Oromo slaves that are well recorded: a family devastated by war, bitter famine, given to an uncle who treated him badly and sold him as a slave, then was ‘passed through several hands … taken in a caravan to a large city’, and then to the coast where he was put aboard a dhow bound for Muscat.[2]

The dhow was intercepted by the Royal Navy vessel ‘Pantaloon’, and one of its officers Lt. Frederick T. Hastings, a high churchman, effectively adopted Salfey and saw to his education.

The African boy was landed at Aden and then taken to Cape Town where he was baptised by Bishop Grey, then brought to England. After several years initial formal education in England, Salfey was taken, or sent, by Hastings to India where he spent four years at the Diocesan High School, Mazazon, Bombay. Finally he returned to England, attending St. Mark’s School, Windsor, where he came under the influence of the Cowley Fathers.[3]

The Rev Stephen Hawtrey, a teacher at St Mark’s, used Salfey as an example of the virtues of a Liberal education. Writing of Salfey, or ‘our Jem’, he said:

Here, then, is a new and unexpected case upon which to try the effect of a Liberal Education. Two years ago the boy was an untutored savage in the interior of Africa; he was about one years under training at St. Mark’s and is now a thorough English boy, and takes rank among his compeers. The school has got hold of his affections and is now moulding his character. He is an intelligent boy with a sweet disposition and reverent spirit. He is much interested about getting on in school, doing his evening lessons well, and getting good reports, as any boy in the School. His instincts are gentlemanly; he cannot bear to be taken out from among his companions for any special notice or attention.

In 1879, much to the delight of his adopted father Frederick Hastings, Salfey was one of the original students at Dorchester College in Oxfordshire where he received his theological training. Salfey was ordained deacon by the Bishop of Oxford in 1882 for service with the Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA).[4] In East Africa he was listed as an ‘African deacon’ even though he was effectively a black Briton.

One contemporary cleric in England wrote: ‘and had it not been for his dark skin no one could have told him from a cultured and Christian English gentleman’.[5]

It is not clear whether he was paid at ‘native’ rates which were lower than those received by his fellow white missionaries. He certainly came home on leave to England in 1889 and 1890, when he was ordained priest, and again in 1894, but for reasons unknown he decided to leave the UMCA and join the Cowley Fathers.[6] According to Anderson-Moorhead, Salfey served as a curate at Clewer, near Windsor, an Anglo-Catholic centre, and spent some time at Cowley, near Oxford, before sailing to join the order in Cape Town in September 1894.[7]

It is not known if Salfey volunteered for overseas mission or if he was directed there because of his African origins. In some UMCA literature he was referred to as ‘African priest’, and when on leave in England and preaching at services the press at times reported him as ‘a native missionary’ or condescendingly commented on his ability to speak English fluently.[8] On arrival in southern Africa, Salfey joined the newly created diocese of Lebombo in what is now southern Mozambique.

Salfey may have been invited directly by William Edward Smyth, the bishop of Lebombo, to serve as a missionary priest. Smyth wanted Anglo-Catholic men for his diocese, and his view of South Africa was ‘that natives did not look with special favour upon white faces, in consequence of the conduct of some of the white traders who had preceded him’.[9] Salfey was of the correct theological hew, and his colour might be of advantage. Certainly, Salfey became a popular figure in the diocese, respected by his fellow priests. He served for nearly 20 years, marrying Mary Worsfold, a white fellow missionary in 1904. Broken in health he retired in 1914 and died on board ship en route for home.

Among those who worked in the diocese with Salfey were two Africans who had received their theological education in England. Gregory Ngcobo, from Zululand, as a boy of 14 had been sent to study at the Anglo-Catholic Hurstpierpoint College in Sussex. From there he moved on to three years at St Augustine’s Canterbury. By the time he returned to southern Africa he had become a very Anglicised African. He regularly played cricket on the fields of Sussex and Kent.

Philip Mkize (c.1873-1943), also from South Africa, studied at the theological college at Burgh and at St Augustine’s, being ordained deacon in St Paul’s Cathedral in 1900. Unable to leave for southern African due to the war, ‘the Archbishop of Canterbury, with the concurrence of the Bishop of Lincoln, gave Mr. Mkize leave to serve for a time as curate to Canon Smyth in the parish of Elkington’ in East Lindsay in 1900-01. This was reported as a useful ‘time spent in practical work at Elkington … as he has been able to minister to English people as well as natives’.[10]

[1] Edward A. Alpers, ‘The other middle passage: the African slave trade in the Indian Ocean’, in Emma Christopher, Cassandra Pybus, and Marcus Rediker, eds, Many Middle Passages: Forced migration and the making of the modern world (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2007), pp. 20-38. On children see Fred Morton, ‘Small change: children in the nineteenth century East African slave trade’, in Gwyn Campbell, Suzanne Myers, and Joseph C. Miller, eds, Children in Slavery Through the Ages (Athens, OH, Ohio University Press, 2009), Lindsay Doulton, ‘The Royal Navy’s anti-slavery campaign in the western Indian Ocean, c.1860-1890: race, empire and identity’, PhD thesis, University of Hull, 2010.

[2] See Sandra Rowoldt Shell, Children of Hope. The odyssey of the Oromo slaves from Ethiopia to South Africa (Athens, OH, Ohio University Press, 2018), pp. 30-32, 73-94 and 191-96.

[3] Salfey rehearsed his early life in two talks in 1882, to meetings of the SPG, one Grantham, the other in Lichfield, see Grantham Journal, 23 September 1882, p.3, and Lichfield Mercury, 13 October 1882, p. 8. His experience of enslavement and rescue from a dhow he often used to great effect, for example to students at Felsted School, Essex, see Essex Herald, 6 March 1888, p. 3. [for Cowley Father papers see CoE Record Office]

[4] The Times, 3 June1890, p. 12, and Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 7 June 1890. Lambeth Palace Library. Benson papers, 89 ff 351-3, letters on the ordination of Salfey (James Challa) missionary in Zanzibar, 1890. The Bishop of Oxford asked E.W. Benson, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for permission to ordain Salfey as a priest, the request being procedural and not to do with Salfey’s suitability.

[5] Rev. Roderick Murchison, Minor Canon, Bristol Cathedral, in a letter to the “Western Daily News, 10 May 1887, p. 7.

[6] On the Cowley Fathers (Society of St John the Evangelist see Rowan Strong, ‘Origins of Anglo-Catholic missions: Fr Richard Benson and tie initial missions of the Society of St John the Evangelist, 1869-1882’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, lxvi (2015), pp. 90-115.

[7] A.E.M. Anderson-Moorhead, History of the Universities Mission to Central Africa 1859-1896 (London, 1897) pp. 162-163, 225 and 250. Salfey’s career can be followed in Central Africa, the UMCA journal, although the references are infrequent’, in Lebombo Leaves, the annual reports of the Lebombo diocese, in the Church Times, and in the English press. See also W.H.C. Malton, The Story of the Diocese of Lebombo (London: The Church House, The Lebombo Home Association, 1912).

[8] E.g Church Times, 16 November 1900, p. 561.

[9] Smyth speaking at an SPG meeting in Manchester, Manchester Courier, 2 December 1896, 6.

[10] Diocese of Lebombo: Annual Report, 1900, p. 15, and Annual Report, 1901, p. 10. Canon James Grenville Smyth, vicar of Elkington, and of Elkington Hall, was related to Bishop William Edmund Smyth of Lebombo.