Source: Ethiopian cable: Issue 304 | October 14, 2025

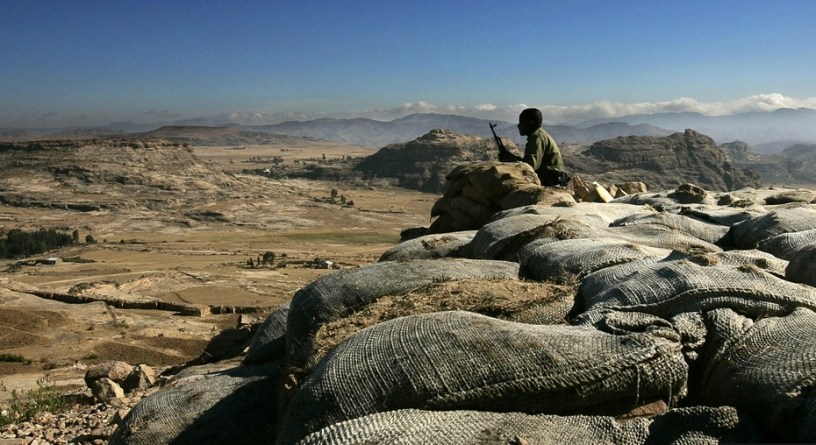

During the 1998-2000 Eritrean-Ethiopian war, such were the political and cultural affinities between the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) that it was routinely described as ‘Brothers at War’ by onlookers. In one attempt to “make sense” of how their alliance soured, Kjetil Tronvoll and Tekeste Negash borrowed the phrase for their book’s title, outlining the collapse in ties post-Eritrean independence and the resulting bloody inter-state conflict between the two Tigrinya-speaking peoples. Yet barring the ‘second front’ within the Somali Regional State (SRS), it remained essentially a contained conflict, a pointless war that left tens of thousands dead. Today, however, with war seemingly on the horizon again between Addis and Asmara, the constellation of actors and alliances is markedly different to 1998-2000, and there is little suggestion that any replay of this conflict could be easily contained.

One merely has to look at the metatised conflict in neighbouring Sudan, where an array of neighbouring and ‘Middle Powers’ are now intimately involved in the raging war. Most prominent are the Arab and Gulf powers of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, but others to greater or lesser degrees are implicated as well, including Qatar, Türkiye, and Iran. Such competing strategic interests range from Russian interest in a Red Sea naval facility to Emirati agricultural investments to the Qatari sponsorship of revived Islamist factions. In many ways, the Sudan conflict is the epicentre of a broader, years-long, seemingly irrevocable political shift in the Horn of Africa towards the Gulf, all jostling for power over the littoral administrations on the Red Sea. In turn, any war for Assab between Ethiopia and Eritrea could well draw in many of the vested interests of the Gulf and from further afield as well. But perhaps most importantly, whether the UAE—Addis’s now closest ally—would countenance funding another war in the region and on the strategic waterway remains unknown.

Eritrea, too, has played an increasingly influential role in the trajectory of Sudan’s conflict, ingratiating itself with the military by arming and training thousands of fighters drawn from eastern Sudanese communities central to the retaking of Khartoum this year. Following the devastating series of drone strikes by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on formerly secure locations in and around Port Sudan in May, the Sudanese army temporarily relocated military aircraft to Asmara to protect them from future barrages. And just this past weekend, the ‘civilian’ Sudanese PM Kamil Idris travelled to Asmara, accompanied by a host of senior military officials, to cement ties with the Eritrean regime. Political and economic committees were agreed to be established to help oversee new ventures such as gold and oil refineries, while Idris thanked Asmara for the “great support they have provided to Sudan in these exceptional circumstances.”

Any such intersection of war between Ethiopia and Eritrea with the Sudan conflict is of particular concern to Addis. In June, Addis reportedly dispatched spy chief Redwan Hussein and Advisor on East African Affairs to the PM Getachew Reda to entreat with senior Sudanese military officials not to engage if Ethiopia were to invade Eritrea. Such an ask, however, feels increasingly unlikely, due to the close Port Sudan-Asmara relationship as well as Cairo’s crucial support for the Sudanese army, with Egypt and Ethiopia at loggerheads over the use of the Nile waters. Whether the Sudanese military can afford to divert men and arms from the raging Kordofans and its own battlefield would have to be seen, but it is more probable that it could facilitate destabilisation on Ethiopia’s western flank. There are several pressure points along this long, porous border, with intermittent clashes between Sudanese and Ethiopian troops over contested territory in the highly fertile region of Al-Fashaga having occurred since the Tigray war, for instance.

Cairo, too, is undoubtedly itching to strike back at Addis, having been outmanoeuvred on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Another increasingly close ally of Asmara– epitomised by the signing of a new Tripartite Alliance with Somalia last year, Cairo would likely attempt to seize on any opportunity to destabilise Addis in the case of war with Eritrea. Egypt has already dispatched military trainers and significant quantities of armaments to Asmara in 2025, and could even theoretically deploy aircraft carriers to the Red Sea in the event of Assab’s seizure, enacting a blockade to render it commercially and militarily worthless. Meanwhile, another latent threat to Addis on its southern flank stems from the recent Egyptian military deployment to Somalia, a presence that has made Addis deeply uncomfortable.

So rather than any contained border war or rapid seizure of Assab, the same alliances from Sudan are instead likely to be transposed onto any conflict between Addis and Asmara. One vast interconnected conflict sphere stretching from Darfur in western Sudan to the Bab al-Mandab would engulf the Horn, splintering and leading to numerous unforeseen circumstances. How that would intersect with Ethiopia’s own internal vulnerabilities and insurgencies—far greater today than in 1998—would have to be seen, but Asmara, again perhaps with support from its Egyptian and Sudanese allies, would surely seek to exploit them.

Eritrea already continues to arm and train elements of the Fano militias in the Amhara region, directing weapons through the porous Sudanese border and along the Tigrayan front. With the support of Eritrea over the past two years, the Fano insurgency has gradually transformed into a far more cohesive and effective fighting force, with increasing reports of major pitched battles between the militias and the Ethiopian military in Gojjam, Wollo, and Gondar. Further, much of Ethiopia’s peripheries are also teetering on the edge of full-blown insurgency or inter-communal conflict, and the requisite diversion of military forces to any northern invasion could further open the door for gains from groups such as the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) as well.

To the south, another– less potent– threat to Addis lies in the possibility of reactivating the former ‘second front’ from Somalia. During the 1998-2000 Badme war, Asmara supported the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) incursions into Ethiopia from territories in Somalia under Hussein Aidid’s control. At that time, Ethiopia similarly backed armed groups in southern Somalia opposed to Aidid, as well as forged closer ties with Omar al-Bashir’s regime in Khartoum to pressure Asmara via the Eritrean Islamic Salvation and other Sudan-based rebel groups. While both the ONLF and OLF disarmed in separate peace processes in 2018 when Abiy came to power, the former in particular has increasingly warned of a return to the battlefield as a result of Addis and Jigjiga’s reneging on the peace deal. War against Eritrea is one prospect, but conflict on three fronts alongside internal instability is another matter altogether.

Eritrea will likely seek to make life as unpleasant as possible for Addis on the international stage, not only by rallying diplomatic opposition to the war with Saudi and Egyptian support, but to dissuade foreign investment as well. Support from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund for the battered Ethiopian economy would likely be withdrawn or suspended, as it was during the Tigray conflict, and Addis would struggle to present a face of strength and stability with multiple, splintering conflicts in its peripheries. And yet, seizing Assab remains eminently possible, as Ethiopia has been revealed to be sourcing sophisticated military jets from Russia, including as many as 6 Su-35s, along with other armament purchases from Algeria and Iran, according to a recent leaked document. Though the Ethiopian military has lost much of its competent officer corps since the calamitous 2020-2022 Tigray war and is bogged down in Amhara, Addis could still launch an offensive against Eritrea– and would be able to inflict substantial aerial damage.

In light of the deepening ties between the Sudanese military and Asmara, the question is perhaps not whether Ethiopia can afford to open a front against Eritrea, but whether it can afford to open multiple fronts against multiple adversaries. A replay of 1998-2000, however bloody and grim that conflict was, appears unlikely, with Ethiopia not only surviving that war but also eventually rebounding even stronger. Today, a war on multiple fronts against such adversaries could threaten not only Ethiopia’s economic stability but even Abiy’s political survival.

The Ethiopian Cable Team

Insiteful article.